- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

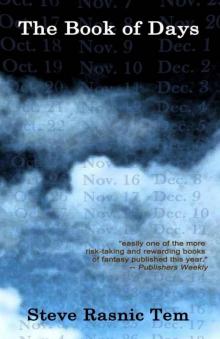

The Book of Days

The Book of Days Read online

THE BOOK OF DAYS

By Steve Rasnic Tem

A Macabre Ink Production

Macabre Ink is an imprint of Crossroad Press

Digital Edition published by Crossroad Press

Digital Edition Copyright 2010 / Steve Rasnic Tem

LICENSE NOTES

This eBook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This eBook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return to the vendor of your choice and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Meet the Author

Steve Rasnic Tem was born in Lee County Virginia in the heart of Appalachia. He is the author of over 350 published short stories and is a past winner of the Bram Stoker, International Horror Guild, British Fantasy, and World Fantasy Awards. His story collections include City Fishing, The Far Side of the Lake, and In Concert (with wife Melanie Tem). Forthcoming collections include Ugly Behavior (crime) and Celestial Inventories (contemporary fantasy). An audio collection, Invisible, is also available. His novels include Excavation, The Book of Days, Daughters, The Man in the Ceiling (with Melanie Tem), and the recent Deadfall Hotel. In this Edward Gorey-esque, Mervyn Peak-esque novel a widower takes the job of manager at a remote hotel where the guests are not quite like you and me, accompanied by his daughter and the ghost of his wife—”a literary exploration of the roots of horror in the collective unconscious.”

Steve Rasnic Tem’s short fiction has been compared to the work of Franz Kafka, Dino Buzzati, Ray Bradbury, and Raymond Carver[citation needed], but to quote Joe R. Lansdale: “Steve Rasnic Tem is a school of writing unto himself.” His 200-plus published pieces have garnered him a British Fantasy Award, World Fantasy and a nomination for the Bram Stoker Awards.

NOVELS

Deadfall Hotel

Excavation

The Book of Days

WITH MELANIE TEM

Beautiful Stranger

Daughters

In Concert

The Man in the Ceiling

COLLECTIONS

Absences: Charlie Goode’s Ghosts

Celestial Inventory

City Fishing

Decoded Mirrors: Three Tales After Lovecraft

Fairytales

The Far Side of the Lake

The Hydrocephalic Ward (poems)

DISCOVER CROSSROAD PRESS

Visit us online

Check out our blog and

Subscribe to our Newsletter for the latest Crossroad Press News

Find and follow us on Facebook

Join our group at Goodreads

We hope you enjoyed this eBook and will seek out other books published by Crossroad Press. We strive to make our eBooks as free of errors as possible, but on occasion some make it into the final product. If you spot any errors, please contact us at [email protected] and notify us of what you found. We’ll make the necessary corrections and republish the book. We’ll also ensure you get the updated version of the eBook.

If you’d like to be notified of new Crossroad Press titles when they are published, please send an email to [email protected] and ask to be added to our mailing list.

If you have a moment, the author would appreciate you taking the time to leave a review for this book at your favorite online site that permits book reviews. These reviews help books to be more easily noticed.

Thank you for your assistance and your support of the authors published by Crossroad Press.

THE BOOK OF DAYS

For the folks who read it first on Genie

and, of course,

for Melanie.

SEPT. 1

He arrived in the small country town in the morning. He immediately went to the local stationery shop and bought all the calendars he could find, over $300 worth. The young clerk’s hands were shaking when she handed him the bags full of his purchases. He was particularly interested in the sixteen month calendars which began on September 1, his birthday and the first day of his new life here.

Calendars were arbitrary constructions anyway– why not one that began on his birthday? Linda would have said he was crazy.

He would have said this trip was meant to keep him from going crazy. If he had been able to talk to her.

He didn’t want to think what his children might have to say.

He went back to the cabin and spread his calendars all over the floor of the one room. Art and photography calendars went along the outside edges of his collection, “On This Day In History” and “Peculiar Facts” types of calendars went on the inside.

He picked up the two that looked most interesting and gazed at September 1. 1875: Edgar Rice Burroughs is born. His favorite author when he was a boy. Now Parker’s favorite. During the long summer the twelve-year-old had read a third of the Tarzan books. 1916: Congress passes the Owen-Keating Act. The child labor law. Child labor had been a horror, especially in the southern mills during his grandfather’s time. Little kids mangled by machinery– that’s the photograph that should have gone on the September page, not some flower or movie star. 1983: The Soviet Union shoots down a South Korean airliner, killing 269. How many children? He used to know, but now he couldn’t remember. Bad things happened to children all the time, and there was nothing he could do.

The worst thing a father can do is abandon his children. There is no excuse. The absolute worst thing. But that’s what he’d done. Continued to do.

No excuse. But he’d frozen up. He couldn’t do it anymore. Afraid of the risks, all the things that might happen, afraid of life. Afraid to let them go anywhere, do anything. God knows afraid to discipline them in any way. All the things that might happen. Afraid of what might happen to Linda if either Parker or Jennie died. Afraid of what might happen to him.

So he’d left his wife and children, taking just enough of the savings to live on, and come here where his mother and her old friend had raised him that first year.

His mother had believed that all the important things in life could be learned from stories. Her own father had told stories to her every day, and after she’d run away from that little country hospital the first day of his life, scared and all broken up inside, she’d told them to him, one each day even though he was too young to know what she was talking about. One each day, like some backwoods Scheherazade, afraid of what her drunken husband would do to her if he ever found her, afraid of what he’d do to the baby he’d never wanted. Terrible things happened to children. Even in fairytales. So the first story she’d ever told him was a nightmare. A nightmare about how he’d been born.

Not that he’d been aware. She told him all these things years later: about his father, about that night, about the stories. She said she shouldn’t have told a baby such a terrible story, but that night it had been the only story she knew. She’d forgotten all the others. But she would apologize to him, again and again. He couldn’t have heard her, could he? He couldn’t have known. It was just his first day.

His mother had never understood. He’d known because he’d lived the story. It just took him a while to remember it. She’d only reminded him of it. So it wasn’t strange at all that the first story he tried to tell himself after he ran away from his wife and children– the first story out of all those he remembered, made up, or retrieved out of some dark somewhere in order to repair himself– was this story. The story of September 1. The story of his first day.

His mother had a neighbor lady take her to the hospital in the middle of the night. She’d walked three miles to the lady�

�s house, not having a phone and besides she didn’t want her husband knowing. He was sleeping it off thank god because if he’d been awake he would have killed them both, pulled that monster right out of her and thrown it in the creek– he’d promised it a hundred times.

The hospital there only had one doctor and he was asleep a bottle in his hand and when they dragged him into the delivery room he turned pale and shook his head because he’d known her all her life he was a good man a kind man but he drank too much like almost every other man she knew. Including her father.

The baby started coming out and the nurses were all excited. “Look how big he is!” one of them cried (ten pounds she found out later) and there was so much blood she couldn’t believe it and the doctor reached down and pulled and she could feel herself breaking inside the baby was so afraid to come out.

The doctor stepped back and one of them said, “Don’t drop the baby!” And she could feel him slipping out of her, slipping away from her forever when the nurse stooped down and caught him before his head hit the floor and scattered his dreams across the delivery room (and wouldn’t those be a chore to clean out of linoleum!).

He’d cracked her pelvis in two places but lucky for her they got the bleeding under control. She was in a lot of pain but she left the hospital anyway in the middle of the night headed through the woods to her friend’s house who knew a little nursing. Her husband would be awake soon. She could feel his eyelids lifting like two scabs peeling off an infected wound and no way was she going to let him catch up to her in that hospital bed.

So it was through the gray woods with her husband wrapped in his shadows waking and her baby sleeping, falling headfirst into nightmare as she passed the black animal shapes she knew she would be telling her son about in story after story after story.

SEPT. 2

1917: Cleveland Amory is born.

1969: The final episode of the “Star Trek” TV series airs.

Strange how the events in these calendars were always presented in the present tense, as if they are happening now, are continuing to happen.

Every year around his birthday he got a headache. It never failed. Every year as the anniversary of his mother’s death approached he experienced cold sweats, chills, and a shortness of breath. Every year as the season neared in which Linda had miscarried the child who would remain forever nameless, he found himself crying as if for no reason. He knew that some day he would have to tell that child’s stories, just as he would tell the stories of his other children.

The important events in his life were like tuning forks, resonating through all the years of his life. Were historic dates similar slices of time which echoed, however faintly, at varying strengths through the strata of a society?

Dates were ghosts. Pulling. Annoying. Nagging.

That first night after his mother had fallen asleep she dreamed that her baby had suffered irreparable injury. His head had been damaged– fluid had accumulated. She dreamed he became a hydrocephalic like her cousin Emily’s child, but more so. His head grew and grew until she was sure it would explode.

Other children with injured, swollen heads came to her bedside and stood with her son. Her son couldn’t speak for fear his head would explode, but his thoughts slipped between her thoughts without effort. If these children cannot let go of their unused lives a cataclysm may occur, he told her.

Momma, do something. And he began to cry. The other children with swollen heads cried with him.

“I’m here. It’ll be all right, babies. I’m here,” she would have told them. But she could not speak because it was a dream. Terrible things could happen to children, she knew. Their heads could explode. And yet there was nothing she could do.

Finally the pressure of their unused lives became so great that their noses, their ears, even their little anuses began to screech and whistle. Their eyes grew wide and pupil-less and still the screeching grew in volume.

Eventually their bodies faded until only the screeching remained. And eventually the screeching stopped, leaving a thin line breaking through the sky, the vulva which would lead them into another world.

SEPT. 3

1939: Britain and France declare war on Germany.

1943: Italy surrenders.

When he was a boy Cal had spent hours with a collection of toy soldiers and a mound of dirt in the back yard. There were traces of this mound, and the trails and bunkers carved into it, in the land behind the cabin today. His solitary red soldier, larger than the rest by a third, played a pivotal role in the scenarios he played out here hour after hour, day after day. The red soldier was always leading his troops into danger, then leaving it to someone else to get them out of it. “Things turn out,” the red soldier might say. “You have to be ready. War is hell and duty is hard.”

Every afternoon the red soldier was killed. Usually at the hands of his own men, with Cal facilitating. Sometimes he was stabbed, once strangled by two tiny plastic soldiers who climbed his back to get to that thick red neck. More often he was shot, his body pierced by so many bullets daylight might shine through. A few times Cal imagined the red soldier’s head taken off by a mortar shell, and so wrapped up had he been in his play he brought his mother’s butcher knife out to the battleground to make things realistic, but he always stopped himself, because he just could not give up the pleasure of killing the red soldier again and again, day after day.

Often his mother came out of the house and sat in a lawn chair by the battleground and watched Cal act out the various fates of the red soldier. He tried to ignore her, but she insisted on telling the war stories her husband had told her, droning on and on with these countless, grim tales of war, until finally they became an almost necessary background narration for Cal’s plays.

“He and some of his buddies came upon a barn in a rural part of France. They thought there were German soldiers inside. Your father was sure of it– he said they had no choice. So they burned the barn. A French farmer and his two children perished in the fire. There were no Germans there, you see? Your father used his mistake to illustrate to me how things happen in war, how you never can tell. You had to be prepared for the unexpected. I could have told them– you get my husband around, and someone’s bound to die.”

Cal had never been in a war, so he didn’t have war stories to share with his children. He didn’t know for sure if they were better off because of this or disadvantaged. At least he was incapable of glorifying war. But he also understood a child’s need to experience what the parent has not. In that case, he may have encouraged an increased danger in their future lives.

It was maddening. There was no right thing, no fool-proof way to provide a healthy example for his kids. Everything he did– whatever his intentions– had the potential to turn out badly.

War stories. Everything he did in order to protect and preserve his children became just another war story.

SEPT. 4

1908: Richard Wright, author of Black Boy, is born.

It was ironic, in view of his father’s legendary prejudices, that the major reason he was never able to find Cal’s mother was because she had moved in with a black woman named Cora, an old friend she’d never dared tell her husband about.

The cabin had been in Cora’s family since just after the Civil War. She told his mother that she was to consider it her own, that she and Cal were family now, and they did, but knowing deep down the cabin and the surrounding land were Cora’s, and always would be.

Even now the place felt like Cora’s, despite the fact that she had died when Cal was only ten years old. The walls still smelled faintly of the roasted pigs and deer that the old woman had practically lived on. And the colors, the curtains, were still the kind– if not the same ones– Cora would have used. And the storage shed by the back yard– the one that still had a few of Cal’s old toys in it: wind-up cars and figures that moved jerkily as if trapped in an explosion of nerves– was a structure Cora had ordered built.

“Real families gots

storage. If this family, you and me and Cal is gonna be a real family, then it’s gots to have storage. You ain’t gots storage, then it means you always ready to leave.”

Cora was almost as important a presence in his early life as his mother. She was broad as the refrigerator and her hair was the silver of dew in the dawn. Practically from the moment he could talk he’d called her “Gramma,” and neither Cora nor his mother had ever bothered to correct him. In that small southern town it had invited comment, of course, but Cal had never paid much attention. Even the last few years before Cora’s death, when Cal was certainly old enough to know better, he chose to call her Gramma.

“Grammas ain’t blood, just like mommas and poppas ain’t blood,” Cora would say to anyone who might ask for some explanation. “Family’s all in the treatin’. Guess that’s why they calls it a tree, you know? It’s what gives you the shade. Don’t much matter where the roots go.”

Two weeks before Cora died she had a stroke. Cal saw her fall, and she was like a tree in the falling. Hard and slow and final. He would never forget it, and he cried when his mother told him Cora was going to die, that he was going to lose his gramma. Then his mother told him that Cora had given the land and the cabin to them, so that they might stay away from “that monster of a man who calls hisself a daddy” forever.

Cal and his mother stayed by her bed, but she never woke up again. The doctor said there was no point in taking her to the county hospital. And it was like waiting for a fallen tree to get up– Cal just knew it wasn’t going to happen.

For months after her death Cal would wake up in the middle of the night and see her standing there in his room, tall and silent and just watching. Funny how it didn’t scare him at all. He guessed she was just shading his dreams was all.

Cora would be ashamed to see him now. He was a poor excuse for a tree. How could he just stand there and watch, and shelter, knowing the teeth and the claws that surrounded his children wherever they went, the animal eyes out in the dark woods waiting? He was a monster, calling himself a daddy.

SEPT. 5

1975: Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme attempts to assassinate President Gerald R. Ford.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

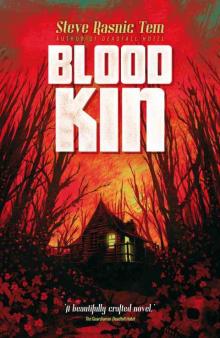

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin