- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

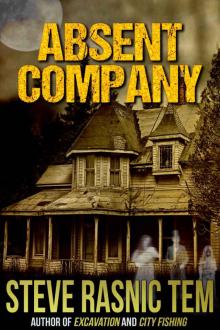

Absent Company

Absent Company Read online

ABSENT COMPANY

By Steve Rasnic Tem

A Macabre Ink Production

Macabre Ink is an imprint of Crossroad Press

Digital Edition published by Crossroad Press

Digital Edition Copyright 2014 / Steve Rasnic Tem

Partial cover image courtesy of:

Obsidian Dawn

LICENSE NOTES

This eBook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This eBook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return to the vendor of your choice and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Meet the Author

Steve Rasnic Tem was born in Lee County Virginia in the heart of Appalachia. He is the author of over 350 published short stories and is a past winner of the Bram Stoker, International Horror Guild, British Fantasy, and World Fantasy Awards. His story collections include City Fishing, The Far Side of the Lake, and In Concert (with wife Melanie Tem). Forthcoming collections include Ugly Behavior (crime) and Celestial Inventories (contemporary fantasy). An audio collection, Invisible, is also available. His novels include Excavation, The Book of Days, Daughters, The Man in the Ceiling (with Melanie Tem), and the recent Deadfall Hotel. In this Edward Gorey-esque, Mervyn Peak-esque novel a widower takes the job of manager at a remote hotel where the guests are not quite like you and me, accompanied by his daughter and the ghost of his wife—”a literary exploration of the roots of horror in the collective unconscious.”

Steve Rasnic Tem’s short fiction has been compared to the work of Franz Kafka, Dino Buzzati, Ray Bradbury, and Raymond Carver[citation needed], but to quote Joe R. Lansdale: “Steve Rasnic Tem is a school of writing unto himself.” His 200-plus published pieces have garnered him a British Fantasy Award, World Fantasy and a nomination for the Bram Stoker Awards.

NOVELS

Deadfall Hotel

Excavation

The Book of Days

WITH MELANIE TEM

Beautiful Stranger

Daughters

In Concert

The Man in the Ceiling

COLLECTIONS

Absences: Charlie Goode’s Ghosts

Celestial Inventory

City Fishing

Decoded Mirrors: Three Tales After Lovecraft

Fairytales

The Far Side of the Lake

The Hydrocephalic Ward (poems)

DISCOVER CROSSROAD PRESS

Visit us online

Check out our blog and

Subscribe to our Newsletter for the latest Crossroad Press News

Find and follow us on Facebook

Join our group at Goodreads

We hope you enjoy this eBook and will seek out other books published by Crossroad Press. We strive to make our eBooks as free of errors as possible, but on occasion some make it into the final product. If you spot any errors, please contact us at [email protected] and notify us of what you found. We’ll make the necessary corrections and republish the book. We’ll also ensure you get the updated version of the eBook.

If you’d like to be notified of new Crossroad Press titles when they are published, please send an email to [email protected] and ask to be added to our mailing list.

If you have a moment, the author would appreciate you taking the time to leave a review for this book at your favorite online site that permits book reviews. These reviews help books to be more easily noticed.

Thank you for your assistance and your support of the authors published by Crossroad Press.

Among the Living first appeared as a limited edition novella from Delirium Books, 2011.

The remaining stories (as well as the introduction) first appeared in the author’s collection The Far Side of the Lake, Ash-Tree Press, 2001

ABSENT COMPANY

CONTENTS

Introduction: Speak Softly and Listen

At the Bureau

Crutches

The Bad People

Leaks

Stone Head

Mirror Man

The Sky Come Down to Earth

Houses Creaking in the Wind

Grim Monkeys

Rider

Escape on a Train

The Far Side of the Lake

Presage

Derelicts

Aquarium

In the Trees

Among the Old

The Little Dead Girl

In a Guest House

Underground

Dark Shapes in the Road

Decodings

At the End of the Day

Fogwell

Ice House Pond

Charlie Goode’s Ghosts

Introduction: Hauntings: The Power of the Past

The Dancers in the Leaves

Hearts

Bouquet

The Snow People

Cutlery

Absences

Goode Farm

Among The Living

Introduction

Speak Softly and Listen: Tales of the Invisible

I was nine, the oldest of three boys, when my parents decided it was time to move me into a bedroom of my own. The fact that it was getting more than a little crowded with my brothers and I in the same bed, and that I had recently discovered the perverse pleasure of tormenting them after the lights went out, were no doubt contributing factors. “You’re gonna be damn sorry if I have to come in there,” had become my father’s favorite post-bedtime admonition.

They moved me into the only room available: “the front room”, also known as “the guest bedroom” (not that I can recall a single guest spending the night in our home, but I suppose good etiquette requires such preparation). Now and then it was also referred to as “the sick room”—the place to which we were banished when a risk of contagion was suspected.

I didn’t much like my new room. Although it was supposedly my bedroom, I wasn’t allowed to move any of my things into it, so it was really just a sleeping room. I think my mother was never quite able to let go of the promise of “guests”. So this spare room was kept pretty much the same as it had always been: the nicest bed, the nicest sheets, flowery decorations, and one of the only scatter rugs in our house at the time. A stranger’s room, a room from someone else’s home—certainly not from ours.

The neatest thing, for me, was the large dresser, once I realized that my mother never inspected the drawers. These were for storage, and virtually forgotten. My investigations uncovered a stockpile of linens and ancient clothes which had not seen the light in decades. And at the back of the bottom drawer a nest of tiny, hairless mice babies (although now I think they may have been rats). I’d never seen such a thing. In fact they were so strange looking I at times convinced myself that they might be some rare breed of miniature pig. My private pets.

There was also a tree outside the window which became so linked to this guest room in my mind that it seemed as much a piece of furniture as the bed or dresser.

I had always dreaded sleeping in this room when I was sick because of that tree. During the day, like as not you’d have seen me sitting in its lower branches, but at night, in the dark, it became something else entirely. It grew taller, spread larger, until I was quite convinced it must overshadow the house. And its limbs were inhabited by all manner of invisible things. That tree outside my new bedroom became everything I knew about the dark. It was the dark, as far as I was concerned. And I was absolutely terrified of the dark.

The intensity of this fear had always embarrassed and hum

iliated me. Certainly I had friends who were scared of the dark, who had to sleep with a light on after an evening watching Shock Theater, but the depth of my own fear made theirs pale into insignificance. I was worse than a baby. I desperately needed to know if someone could die from fright, but I didn’t know anyone I could trust enough to ask. I watched The Tingler every time it was on TV, trying to determine if the events it depicted were possible or not.

I always slept with layers of bedclothes wrapped tightly over my head, even during the hot and humid Virginia summers. Sleeping with my brothers, I’d told myself it was to block the bright light from the hall, or a way to maintain hard-won mattress territory. Once I started sleeping in the guest room, however, I found I could make no more excuses. I covered my head because I was terrified.

There was nothing particularly unique about my fear of the dark, of course. I heard things I could not explain. When I dared peek out from under the covers I invariably saw things that could not be there. Someone was trying to get into the room. Someone had got into the room, and now stood just over there, no more than three feet away, watching me pretend to sleep, and knowing that I was pretending. Kid stuff. Baby stuff.

And everything I tried made it worse. If I took a flashlight into bed with me it only emphasized my isolation, making the night outside my bright circle that much darker. A light on in the room itself made me feel trapped in a dim spaceship, everything outside having ceased to exist. Music played softly on the radio made me even more anxious about the “real” noises the music disguised.

But my worst idea was to cover my ears with my hands. Even now it seems strange to me that I would have chosen this solution which eventually caused me so much terror.

For in covering my ears I uncovered the fragile beat of my own life, the shaky, static-filled pulse which announced not only that I was alive, but that death was a very real possibility.

I used to wonder if the real difference between humans and animals was that human beings were aware of their own pulses. I used to wonder if in the history of humankind anyone had ever heard his or her own pulse stop.

Once when I was about ten, I thought I heard my own pulse stop and I screamed at the top of my lungs until the rest of the family rushed into the room. I was too embarrassed to tell them what was wrong—perhaps I didn’t even know what was wrong—so I told them I thought I saw a face in the window. My brothers ribbed me for days, calling me crazy. But I was too smart to tell anyone what had really frightened me.

Some of my first stories were the stories I told myself in the dark, as a distraction when I could not sleep. What the doorknob became when the family went away. What happened to the cat lost beneath the rug. The separated Siamese twin who awakened to discover that his brother had received their shared soul, leaving him an empty shell.

The very existence of these stories, more than their particular events, haunted me. I never had the feeling I was making up stories. The stories were making up me, one idea, one impression at a time. All I had to do was listen to the pulse of my own blood as it pumped mechanically through every room of the dark house. Speak softly, or don’t speak at all, else I wouldn’t be able to hear it.

To this day I have no particular aversion to graphic horror—I’ve written quite a bit of it myself. I enjoy writing about and reading loving descriptions of hideous creatures and events. But it has always been the quieter works, the ghostly tales of loss and memory and things invisible, which have continued to haunt me.

This preference began all those years ago in the sick room, the stranger’s room, that guest bedroom in which a dark tree, a nest of mice, and the sound of my own too-rapid pulse were part of the furniture. Because I didn’t believe I was completely making up those stories: I was keeping quiet, and listening carefully, and recording the events which no one sees but which grab our hearts and drive our passions. The creatures I sensed in the dark and heard between systole and diastole seemed more real than Dracula or Frankenstein or any of a number of imaginings capable of maiming and dismembering. To my mind the invisible world of passions and presences was not a part of a fantasy genre at all, but as real as the doors and windows and curtains and darkness they possessed. These were the things people thought about, but did not talk about. Rarely do we encounter a monster in the middle of the street ready to eat us (after first torturing us in some detail). Almost as rarely do we meet that monster’s first cousin, the serial killer.

But we are locked alone in our heads every day, forced to listen to these invisible happenings in the dark. More real, more immediate than a thousand graphic entertainments, they require our sustained attention.

Steve Rasnic Tem

Denver, Colorado

2001

At the Bureau

I’ve been the administrator of these offices for twenty-five years now. I only wish my employees were as steady. Most of them last only six months or so before they start complaining of boredom. It’s next to impossible to find good clerical help. But I’ve always been content here.

My wife doesn’t understand how I could stay with the job this long. She says it’s a dead end; I’m at the top of my pay scale, there’ll be no further promotions, or increase in responsibilities. I’ve no place to go but down, she says. Her complaints about my job always lead to complaints about the marriage itself, of course. No children. Few friends. All the magic’s gone, she says. But I’ve always been content.

When I started in the office we handled building permits. After a few years we were moved to peddling, parade, demolition licenses. Two years ago it was dog licenses. Last year they switched us to nothing but fishing permits.

Not too many people fish these days; the streams are too polluted. Last month I sold one permit. None the two months before. They plan to change our function again, I’m told, but a final decision apparently hasn’t been made. I really don’t care, as long as my offices continue to run smoothly.

A photograph of my wife taken the day of our marriage has sat on my desk the full twenty-five years, watching over me. At least she doesn’t visit the office in person. I am grateful for that.

Last week they reopened the offices next door. About time, I thought; the space had been vacant for five years. Ours was the last office still occupied in the old City Building. I was afraid maybe we too would be moved.

But I haven’t been able as yet to determine what it is exactly they do next door. They’ve a small staff, just a lone man at a telephone, I think. No one comes in or out of the office all day, until five, when he goes home.

I feel it’s my business to find out what he does over there, and what it is he wants from me. A few days ago I looked up from my newspaper and saw a shadow on the frosted glass of our front door. Imagine my irritation when I rushed out into the hallway only to see his door just closing. I walked over there, intending to knock and ask him what it was he wanted, but I saw his shadow within the office, bent over his desk. For some reason this stopped me, and I returned to my own office.

The next day the same thing happened. Then the day after that. I then refused to leave my desk. I wouldn’t chase a shadow; he would not use me in such a fashion. I soon discovered that when I didn’t go to the door, the shadow remained in my frosted glass all day long. He was standing outside my door all day long, every day.

Once there were two shadows. That brought me to my feet immediately. But when I jerked the door open I discovered two city janitors, sent to scrape off the words “Fish Permits” from my sign, “Bureau of Fish Permits”. When I asked them what the sign was to be changed to, they told me they hadn’t received those instructions yet. Typical, I thought; nor had I been told.

Of course, after the two janitors had left the single shadow was back again. It was there until five.

The next morning I walked over to his office door. The lights were out; I was early. I had hoped that the sign painters had labelled his activity for me, but his sign had not yet been filled in. “Bureau of …”. A few black streaks

showed where the paint had been scraped away years ago, bare fragments of the letters that I couldn’t decipher.

I’m not a man given to emotion. But the next day I lost my temper. I saw the shadow before the office door and I exploded. At the top of my voice I ordered him away from my door. When three hours had passed and he still hadn’t left, I began to weep. I pleaded with him. But he was still there.

The next day I moaned. I shouted obscenities. But he was always there. Perhaps my wife is right; I’m not very decisive. I don’t like to make waves. The last time we went out to dinner—it must have been years ago—the waitress gave me someone else’s meal. Despite my wife’s pleadings, I could not bring myself to return it. When the intended recipient of the meal complained and the waitress asked me why I hadn’t said anything, I could only shrug.

It’s been days. He is always there.

Today I discovered the key to another empty office adjacent to mine. It fits a door between the two offices. I can go from my office to this vacant office without being seen from the hallway. At last, I can catch this crazy man in the act.

I sit quietly at my desk, pretending to read the newspaper. He hasn’t moved for hours, except occasionally to peer closer at the frosted glass in my door, simulating binoculars with his two hands to his eyes.

I take off my coat and put it on the back of my chair. A strategically placed flower pot will give the impression of my head. I crawl over to the door to the vacant office, open it as quietly as possible, and slip through.

Cobwebs trace the outlines of the furniture. Files are scattered everywhere, some of the papers beginning to mold. The remains of someone’s lunch are drying on one desk. I have to wonder at the city’s janitorial service.

Unaccountably, I worry over the grocery list my wife gave me, now lying on my desk. I wonder if I should go back after it. It bothers me terribly, the list unattended, unguarded on my desk. But I must push on. I step over a scattered pile of newspapers by the main desk, and reach the doorway leading into the hall.

With one mighty swing I leap through the doorway, prepared to shout the rude man down, in the middle of his act.

The hall … is empty.

I am suddenly tired. I walk slowly to the man’s office door, the door to the other bureau. I stand, waiting.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

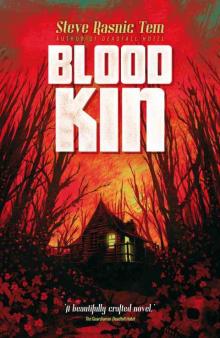

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin