- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling Read online

THE MAN ON THE CEILING

By Melanie Tem & Steve Rasnic Tem

A Macabre Ink Production

Macabre Ink is an imprint of Crossroad Press

Digital Edition published by Crossroad Press

Digital Edition Copyright 2013 / Melanie Tem & Steve Rasnic Tem

Background image courtesy of:

http://mysticmorning.deviantart.com

LICENSE NOTES

This eBook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This eBook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return to the vendor of your choice and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

MEET THE AUTHORS

Melanie Tem’s work has received the Bram Stoker, international Horror Guild, British Fantasy, and World Fantasy Awards, as well as a nomination for the Shirley Jackson Award. She is also a published poet, an oral storyteller, and several of her plays have been produced.

She is a social worker, and also has a freelance editing business.

She lives in Colorado with her husband, writer and editor Steve Rasnic Tem. They have four children and four granddaughters.

www.m-s-tem.com

NOVELS

Black River

Blood Moon

Desmodus

Making Love

Prodigal

Revenant

Slain in the Spirit

The Deceiver

Wilding

Witch-Light

WITH STEVE RASNIC TEM

Beautiful Stranger

Daughters

In Concert

The Man in the Ceiling

WITH JANET BERLINER

What You Remember I Did

COLLECTIONS

Daddy’s Side

The Ice Downstream

UNABRIDGED AUDIOBOOKS

Blood Moon – Narrated by Mikael Naramore

Prodigal – Narrated by Christine Padovan

Slain in the Spirit – Narrated by Ann Richards

Steve Rasnic Tem was born in Lee County Virginia in the heart of Appalachia. He is the author of over 350 published short stories and is a past winner of the Bram Stoker, International Horror Guild, British Fantasy, and World Fantasy Awards. His story collections include City Fishing, The Far Side of the Lake, and In Concert (with wife Melanie Tem). Forthcoming collections include Ugly Behavior (crime) and Celestial Inventories (contemporary fantasy). An audio collection, Invisible, is also available. His novels include Excavation, The Book of Days, Daughters, The Man in the Ceiling (with Melanie Tem), and the recent Deadfall Hotel. In this Edward Gorey-esque, Mervyn Peak-esque novel a widower takes the job of manager at a remote hotel where the guests are not quite like you and me, accompanied by his daughter and the ghost of his wife—”a literary exploration of the roots of horror in the collective unconscious.”

Steve Rasnic Tem’s short fiction has been compared to the work of Franz Kafka, Dino Buzzati, Ray Bradbury, and Raymond Carver[citation needed], but to quote Joe R. Lansdale: “Steve Rasnic Tem is a school of writing unto himself.” His 200-plus published pieces have garnered him a British Fantasy Award, World Fantasy and a nomination for the Bram Stoker Awards.

NOVELS

Deadfall Hotel

Excavation

The Book of Days

WITH MELANIE TEM

Beautiful Stranger

Daughters

In Concert

The Man in the Ceiling

COLLECTIONS

Absences: Charlie Goode’s Ghosts

Celestial Inventory

City Fishing

Decoded Mirrors: Three Tales After Lovecraft

Fairytales

The Far Side of the Lake

The Hydrocephalic Ward (poems)

DISCOVER CROSSROAD PRESS

Visit our online store

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Visit our DIGITAL and AUDIO book blogs for updates and news.

Connect with us on Facebook.

Join our group at Goodreads.

In 2000, American Fantasy Press of Woodstock, Illinois, operated by Robert and Nancy Garcia, published “The Man on the Ceiling” as a novella in chapbook form. That novella became the seed for this book. We gratefully acknowledge the Garcias for launching us on this adventure.

Excerpts from “The Second Coming” by W.B. Yeats by permission of A P Watt Ltd on behalf of Gráinne Yeats, from W.B Yeats, Phoenix Poetry, The Orion Publishing Group, London, 2002.

Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town (Vocal)

Words by Haven Gillespie Music by J. Fred Coots

© 1934 (Renewed 1962) EMI Feist Catalog Inc.

Rights for the Extended Renewal Term in the United States controlled by Haven Gillespie Music and EMI Feist Catalog Inc. All Rights Controlled outside the United States Controlled by EMI Feist Catalog Inc. (Publishing) and Alfred Publishing Co., Inc. (Print) All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission of Alfred Publishing Co., Inc.

For our children, who gave us their blessing.

Everything we’re about to tell you here is true.

THE MAN ON THE CEILING

CONTENTS

1 – Road Trip

2 – Alchemy

Just Her Size

3 – The Man on the Ceiling

Penguins

Penguins

4 – Sense of Place

5 – Naming Names

6 – Elephant Soup

The Elephant’s Ear

7 – Telling Tales

Hideout

Stalked By God

See Me

The Day He Died

School’s Out

Finding Melanie

Tidal Pool

25 of the 487 Rules of Storytelling

8 – Hitting the Quarter-Mark

9 – Asymptote

The Yellow Cat

10 – Down the Dark Stairs

11 – Everything We’re Telling You Here Is True

Awake.

Someone in the room.

Asleep. Dreaming.

Someone in the room.

Someone in the room. Someone by the bed. Reaching to touch me but not touching me yet.

I put out my hand and Steve is beside me, solid, breathing steadily. I press myself to him, not wanting to wake him but needing enough to be close to him that I’m selfishly willing to risk it. I can feel his heartbeat through the blanket and sheet, through both our pajamas and both our flesh, through the waking or the dream. He’s very warm. If he were dead, if he were the ghostly figure standing by the bed trying to touch me but not touching me, his body heat wouldn’t radiate into me like this, wouldn’t comfort me. It comforts me intensely.

Someone calls me. I hear only the voice, the tone of voice, and not the name it uses.

Awake. Painful tingling of nerve endings, heart pumping so wildly it hurts. Our golden cat Cinnabar—who often sleeps on my chest and eases some of the fear away by her purring, her small weight, her small radiant body heat, by the sheer miraculous contact with some other living creature who remains fundamentally alien while we touch so surely—moves away now. Moves first onto the mound of Steve’s hip, but he doesn’t like her on top of him and in his sleep he makes an irritable stirring motion that tips her off. Cinnabar gives an answering irritable trill and jumps off the bed.

Someone calling me. The door, always cracked so I can hear the kids if they cough or call, opens wider now, yellow wash from the hall light across the

new forest green carpet of our bedroom, which we’ve remodeled to be like a forest cave just for the two of us, a sanctuary. A figure in the yellow light, small and shadowy, not calling me now.

Neither asleep nor awake. A middle-of-the-night state of consciousness that isn’t hypnagogic either. Meta-wakefulness. Meta-sleep. Aware now of things that are always there, but in daylight are obscured by thoughts and plans, judgments and impressions, words and worries and obligations and sensations, and at night by dreams.

Someone in the room.

Someone by the bed.

Someone coming to get me. I’m too afraid to open my eyes, and too aroused to go back to sleep.

Chapter 1

Road Trip

Maybe there are families that have never taken trips of any kind together. But—as son, husband, father, even just as observer—I’ve never come across a family that didn’t have its road stories. The Summer We Went to Yellowstone. The Night Dad Drove the Car off the Road Outside Phoenix. Why Mom Hates Delaware.

For many of us, trips with our families are the only grand adventures we will ever have. Others morph the tedium of the experience into tales gently or bitterly mocking.

Sometimes these memories of family travel are fond. Sometimes they’re over-simplified and one-sided cautionary tales explaining why we will never take a driving vacation with our own kids, ever. They become simultaneously inspiration, metaphor, and excuse.

Family life itself is a kind of road trip. Often the route coincides with the map only occasionally and, even then, deceptively.

Melanie and I have adopted five children over the twenty-five years of our marriage. When they came to us (not all at once), they were four, five, six, seven, and ten.

Sometimes when people ask me how we got them I say we found them along the side of the road—since we’d eaten the last of the fried chicken there was a little room left on the back seat so we said sure, why not, hop on in.

When people ask, “How did you know they weren’t going to turn out to be serial killers?” I might rejoin, “How do you know your kids aren’t?”

I understand the need to question. Things do get scary out on the road, and practically every responsible person tells you not to pick up strangers.

But I knew they weren’t strangers. I knew they were my kids from the moment I first glimpsed them through the windshield, standing beside the road with their flimsy little cardboard suitcases.

“Wasn’t it a little dangerous?”

Everything’s dangerous. Even in your dreams. Even if you sleep without dreams. From the moment you jump out of bed and take that first breath. Something terrible might happen. Someone’s bound to die before the story is over. You might even fall in love.

What I’ve been telling you is metaphor. They’re pretty rare in these parts but some days you can actually bag your limit. I’m told they like to travel in packs for added security.

I love my family beyond reason. The fears I have for my family run beyond reason as well. Traveling beyond the lands of reason you enter the kingdoms of imagination and metaphor. Melanie and I are both professional writers of fiction. One of the many disadvantages of that particular occupational choice is that we’ve become quite adept at imagining the worst.

As parents, we’ve also learned that the worst can happen, and somehow the family must go on.

Both as parents and as writers, we’ve come to respect the imagination, but more than that, to understand just how much a family and its members make their lives there. What might happen next.

What they’re going to be when they finally grow up. What their own children will be like. What really happens behind closed eyes, in the middle of a reverie, or late at night when the real world fades into a dream of what happened yesterday.

This memoir—or testament, if you will—is as much a biography of one family’s imagination as a chronicle of real life events. It is about both our love and our fear, about what we know and what we cannot know but can imagine. And although what happens in the imagination may be real in a different way than the apparent history of waking events, it is real just the same.

Like memory itself, this testament travels freely through space and time. At one moment our children are youngsters, crawling across our knees. And then, when we’re not quite prepared for it, they are adults, with children of their own. We began this story as parents, and are surprised to end it as grandparents, as Grandma and Poppie, as Baba and Papa.

You may wonder what really happened to these people. You may wonder where the day’s documentary ends and the dream’s journey begins.

I remember driving for a long time that day: ten to twelve hours at least. The kids had been asleep for hours. Melanie had finally dozed off after a long discussion, not exactly an argument, but it had made me tense. I’ve never done well with conflict, but she never lets me get away with just backing off. Now, I wasn’t even sure what exactly we’d been talking about for all that time, but it had much to do, I knew, with our children, and with what I could see outside our car.

Along the side of the road, as far as the eye could see, the children waited. Some of them were babies, owning nothing but the baskets they were in and their own dirty blankets. Sometimes the older kids—and by “older” I mean two or three years of age—would take care of them, holding and singing to them because that came instinctively, feeding them out of other people’s garbage cans.

The babies’ dreams were elemental. The babies did not dream of parents. They dreamed of warmth and nipples and other good things in their mouths, arms around them keeping them close.

It was the kids old enough to know what families were, or could be, but lacking the cynicism that comes from constant disappointment, who dreamed of parents. Their ideas of what good parents might be were unrealistic, of course, derived as they were from what television shows or movies they had seen. But if there was anything in common in those dreams, it was that the parents were present. They did not go away, they did not vanish into some invisible tear in the world.

I looked around the car, at my own children sprawled into haphazard sleep, their bodies twisted as if dropped from a great height. I never had understood how they could find comfort in these positions: Veronica with her hands under her cheekbones and her butt in the air, Chris with his head upside down and hanging off the edge of the seat, Gabriella with one arm raised as if asking questions of some invisible sleep teacher, and Joe with arms fiercely crossed as if trying to break his own rib cage.

And not for the first time I wondered in what nook or cranny Anthony would have found to make his nest, if he had lived long enough to know Gabby and Joe. I wondered if any of my surviving children ever dreamed of him, of how he was or how he might have been. I wondered about what lessons he might have taught them about death, and how they might use that knowledge. There was so much for them to know, or at least to try to understand. Anthony could be a good teacher— certainly he taught me everything I know about loss.

Outside the car windows the children came in droves. Some had barely escaped house fires: you could see places on their necks bubbled like a plastic toy left on the stove. Some had crawled out of floods or earthquakes, their faces smeared and broken. Some stared with eyes that had seen everything but from which nothing looked back when you gazed into them.

There was no more room in the car. I wanted to stick my head out the window and tell them that, and somehow apologize for it, but frankly there were so many I was afraid. Already there were so many, and they were so close, I was afraid I was going to hit one of them so I drove more and more slowly, then sped up for fear of encouraging them to rush the car. That much need, that much evidence of our failure is terrifying. Sometimes I wonder if we will be judged on how we’ve cared for all our unwanted children and it makes me shudder.

I won’t say I wasn’t tempted, especially by the ones with something wrong in the face, or something more subtle that still managed to keep them separated out from the rest, as if the

y might be mythological creatures in disguise, needing someone to champion what was human, and essential in them. I was tempted. But the car was only so big, and I had only so much time, and as it is I don’t really know what I’m doing—I’m just playing all this by ear.

“You do what you can.” I remember that was one of the things I said to Melanie during our long discussion. “But it isn’t enough,” is what she said back to me and although I tried to talk her out of that notion I knew of course this is true. How do you live with the fact that the very best you can do isn’t enough? I don’t know.

We didn’t adopt our children in order to save them but that doesn’t change the fact that they needed to be saved. We adopted our children because we knew we’d be good parents for them, because already, in a sense, we knew they were ours to parent. Being a parent is not promising you’re going to love a child. Being a parent is having sufficient faith, that strong arm of the imagination, to make that child your own, despite everything you know and everything you can’t even imagine.

What links our family together is not blood, but that kind of faith. Our children, even though they have come to us out of different failures, different disasters, are brothers and sisters because of that faith, that leap of the imagination that has brought their histories together with ours.

We’ve done the best we knew how to do. Minute by minute, we’re still doing our best. We haven’t been able to fix everything.

Despite Chris’s innate innocence, he has spent most of his adult life in and out of prison. He does not set out to hurt anyone, but he has hurt a great many people, and I have to admit that I understand him less now than ever.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

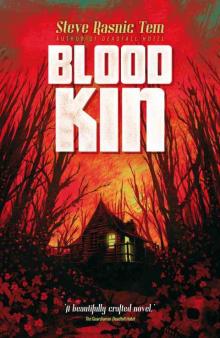

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin