- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

Blood Kin Page 2

Blood Kin Read online

Page 2

It seemed inevitable now that he be here. He’d been on his way back here ever since he left. Even as the red Chevrolet bit into his lower left leg he’d known he was going home. As he flew backwards into the sculpted shrubbery that lined the street he knew his grandmother must be waiting for him, sitting up with his pain in her own ancient legs. It had almost made him feel guilty, but not quite. He’d made another bad decision.

The parlor/sewing room was stacked high with folded materials in dusty red, green, and blue, baskets full of brocade and buttons, chairs piled high with patterns and books and catalogs twenty and more years old. He found his chair by the old Singer, and waited for his grandmother.

To come in. To get on with the story.

He’d been back almost two years. Every night at this time, sometimes a half-hour earlier, never more than fifteen minutes late, she camein here to tell a little more of the family tale, her tale. The first month she had made him come in here, in that cracked voice, that unaccountably compelling way she had, and when he began resisting in earnest she just sat next to him wherever he was, outside on the porch or in his own room, and began to tell the tale again. You couldn’t win against a crazy old lady.

He was thirty years old with no life, living with his grandmother. He couldn’t leave here, and he wasn’t even sure why. He felt like one of those women he used to date — wanting to leave, but somehow she was preventing it. And yet he kept coming back for more.

Once he’d limped out into the woods, almost as far as the resting fingers of the kudzu, and she’d followed him painfully out there, stumbling and sliding — he’d heard her protesting joints from yards away and it almost sickened him, did sicken him when he began feeling it himself. It took him an hour to carry her back to the house, and she’d been bedridden a week.

Every evening of that week he had gone to her bedroom to hear the story. She had talked and he had listened.

Now it was expected that he wait for her in this room. He almost, but told himself “not quite,” detested the old woman, maybe most of all for the waiting. She was pretty much in control of everything.

After all, a rotting iron-clad crate waited for him. Or what was inside, the name he did not know or care to know for fear he’d be calling it down on him, and him so ill-prepared. Not yet. He needed more of his grandmother’s tale.

He couldn’t help listening. For it was also his story.

He sometimes wondered if she would ever let him clean this room, this mausoleum of old cloth and dress patterns. Since he moved in she had had him excavate relics and mementoes and trash from corners and behind stairwells and the backs of built-in drawers and cabinets all over the house, sorting through things thathadn’t seen the light in decades. He imagined taking them from the dim artificial light of the old house into the more intense light of day, and watching them crumple or dissolve or rise into smoky wings circling the house before drifting into the trees. Anything was possible here.

His grandmother would examine each item for flaws, cast some — a very few — away, give others to Michael to look at or do with what he would, and put others back into the cabinets herself.

It was the items she gave him that troubled, because he never could figure out her criteria for the gift. They always looked much the same as the ones not chosen − old letters, newspaper clippings, and bits of toys, buttons, and Christmas ornaments. He would stare at them for hours trying to fathom their secrets, the secrets she meant for him to have.

Most of all, he resented the responsibility she gave him. It was now his decision whether to save any individual item or throw it away. Sometimes this took a long time — he’d look for opinions hidden within her expression but she was blank as stone — and, after all that, he’d change his mind. He’d foolishly scrabble through the trash searching for what he’d thrown away. It disgusted him… the power she had.

Thiswas one of the handmade houses you saw all over this part of Virginia. Piece by piece over the past two years he’d learned that its first owner had beena farmer, a hermit really, by the name of Jacobs. Grandma’s uncle the preacher, Michael’s great great uncle, had bought it from Jacobs. Or obtained it by some other means; Grandmaseemed unwilling to commit herself on that point. One day Jacobs just left town on the back of a broken down mule he’d gotten from the uncle, not saying one word, just staring at the country he was leaving, not even bothering to take most of his belongings. The next day the preacher moved in, where he would live until Grandma’s father finally took over the house.

Michael hadn’t gone far enough into the tale yet to know what happened to the preacher. According to Grandma the present-day parlor was all there’d been to the original house. The woodwork in this room was darker and grainier than anywhere else, and the construction just different enough to show that anotherpair of hands had worked it. Walls and ceiling and broad, shiny floor came together pleasingly in this room, once you subtracted the clutter. The preacher apparently had made no attempt to duplicate such serenity in the rest of the house.

If Michael were to back out of this room, slowly, he would find himself in a narrow hallway that ran up the west side of the house. Back up too quickly and he’d already be in the kitchen, where walls tilted slightly away from each otherso that you might very well go dizzy if you stared too long.

He knew there were a lot of other bedrooms, but he hadn’t ventured into all of them. Some were kept locked. He and Grandma lived in the main part − the part which, despite its architecturaleccentricities, seemed the most normal. He avoided the rest of the house as much as possible. Not all of the rooms were even equipped with electricity.

One day during his first month back he’d gone through the small door off the back of the living room. This led to a series of short hallways with doors branching off. He’d gotten only a few feet through one of them when he’d experienced the distinct sensation of the house unfurling itself into a maze, or a net, or maybe the dry rotting chambers of some great, woody flower. He’d backed out immediately and never tried to explore the place again.

It had been like falling; that memory of an endless succession of rooms dropping away to nothing made it almost unbearable for a while to open any door.

Some nights he would hear Grandma stumbling around back there carrying her kerosene lamp and he would try to force sleep to come.

Grandma told him that the preacher used to leave visitors out front, before there’d been a front porch, and walk into the house, “and it was like the house just swallowed him up. He didn’t come out for days. And everybody said his skin was paler than when he went in, like he’d bleached it.”

“Nobody’d follow him in there,” she said. “Preacher traded for a lot of furniture over them years — for a healing, or running a funeral, or a special prayer, or a guarantee of children or that a marriage goes well – people said he got enough furniture to fill an ordinary house ten times over. But when my mother and me moved into this house it was almost empty. And them were some fine pieces too, old heavy stuff — dressers and cabinets and sideboards and paintings and such.”

Sometimes it seemed to him Grandma was like this house, as was he, as were all his relatives he knew anything about. Rooms inside rooms connecting to even more rooms. And all of them resembling each other. By knowing Grandma he could also know all the relatives who had come before her.

As she told him the stories he was there, seeing the stories and being inside the stories, living them through her eyes. She hadn’t told him much of significance yet, at least nothing for him to act upon, childhood memories of a lamb and playing near the cows, feeding the chickens and the goat, some anecdotes about favorite play pretties and the girl’s worst disappointments, her small sins and her father’s much larger sins, the vileness of his appetites, and the danger he posed to her sanity. But small things, relative to the big thing she promised would lie at the end of her tales.

He’d had a taste of it all his life — that special empathy of the Gibsons’ — he

aring a friend’s memory related and reliving it inside his mind with a felicity so remarkable he might weep with the sorrow of it or gasp breathless with the thrill. Not that he ever did weep, or gasp, but the potential was there. But this was more. When Grandma spoke the words of her life he was there smelling the thirties air of those southwest Virginia hollows and river bottom farms, tasting the tastes of molasses and corn bread and feeling the growing soreness of this blister on her left foot rubbed against the ill-fitting shoe.

It was a perfection of memory he’d rather have been denied. Having to live your own life, however dull, was plenty; there really wasn’t enough room for someone else’s. All that could result from such an overfeeding was pain.

He was pretty sure she knew that, otherwise she wouldn’t have lived alone most of her life. Yet she continued to feed memories to him.

He still had not learned what that awful crate contained, and he had a feeling, a sense disconnected from all reason, that his time was running out. He could hear the wind rustling the trees outside. He imagined the sound of a thousand kudzu leaves shaking in the glen.

Skinny little corn husk of a girl.

Twelve years old.

Her father’s object, target of his frustrated desire.

Michael saw her shadow creeping across the leaning stacks of magazines before he heard her step. Then she was there in her rocker, that little girl suddenly struck old, voice crackling like yellowed newspapers catching on fire, speaking to him, taking him in through the doors…

Chapter Two

SADIE LEFT THE rotting gray shack with her daddy’s shouts still chewing on her ears, and she didn’t know how she could take much more. The man was slipping into craziness a little more each day — just like his own daddy and momma, and Uncle Jesse, too. Most of the back hollow Gibsons got that way after a certain age, at least that’s what her uncle the preacher told her. Said they didn’t have sense enough to use whatever powers almighty God give them, and that’s why they turned sour that way.

Sadie herself didn’t want no powers, didn’t want to know no body that had them. She’d heard there were town Gibsons, normal folk who didn’t talk about such things. Maybe she could go live with that bunch.

“You’ll have to make your choice someday soon, Sweet Sister.” She never could figure out why the preacher’s voicewas so hurtful to hear, just that it went up sharp in places, and he talked about things that made her irritable. You could get a terrible headache listening to the preacher too long, but apparently the folks in his congregation didn’t seem to mind. “You’ll be coming of age,” he’d said, and again she found herself wishing she could stay a child at least until rabbits rode horses. That would be a fine day, she figured, for becoming an adult. She didn’t understand quite yet what being an adult meant; she just knew she wanted no part of it. All the other girls in her class she knew had had their first monthly visits by now, but she was having no part of that either. She’d hold it back, at least until she was out of that house, maybe even out of the county. She knew her daddy was real concerned about it, asking every other day if she was “bleedin yet.” She wasn’t sure what would happen if she said she was. Maybe he’d stop touching her then, but she didn’t think so. She figured it would probably get worse, although she didn’t know how.

She’d stay a girl until she left here — that’d bethe plan. Looking at her mother she saw what being a woman meant.

The thing about Daddy’s craziness was that he played with it so much you couldn’t feel too sorry for him. He spent his crazy spells drinking and betting and having a good time. Her granddaddy, her momma’s daddy, was always talking about that. Her granddaddy hated her daddy, said her momma should’ve never married trash like that. The Morrison branch of the Gibsons being what they were, with a bad reputation among their own kin, and even with them being supposedly one of the oldest Melungeon families in the valley. So maybe she shouldn’t always believe what her granddaddy said.

She couldn’t really believe what any of them said. Not her daddy or her granddaddy, not even her mother. And Lord knows not the preacher.

She had to get out of that house, but she was only twelve years old. Maybe she could get married, but she really didn’t think she wanted to get married, especially to some old fool been married three times already and outlived all three. That Mr. Mackey was on to her daddy all the time about marrying her, and giving her daddy gifts for it, but so far he hadn’t made any promises. Right now her daddy wanted her all to his self, but that might change — he might get tired of her or Mr. Mackey might just sell that barn full of cows of his, to some feeble-mindedman a worse fool than him, and then he’d have just enough marriage money to buy her from her daddy.

She heard a yelling then, looked up and figured she’d gotten too close to the fence around the Younger property, and there come Hattie Younger running hell-bent across the field toward her, a big stick raised in her hand ready to clobber. “Run, Sadie, run! I dont know I can catch her!” It was Hattie’s oldest son Bill, his face red, giving it all he had as he ran after his ma because apparently he’d started too late.

Sadie took off down the road as hard as she could, but she’d never been a good runner, and Crazy Hattie was bound to catch her for sure, and beat her head in with that big stick. Hattie lost her mind about seven year ago — Momma said that just happened to folks around there sometimes — and for some reason she got it into her head that Sadie had done her a terrible wrong, and she was for sure going to even the score. It made no sense — Sadie knew Bill from the one-room school up on the hill — but she hardly knew the rest of the family at all, and didn’t think she’d ever even spoke to Hattie. But Hattie was screaming at her now, and when Sadie turned her head around to see, Hattie was in the road only a few yards behind, her big straw hat flapping up and down, and every time it flapped up Sadie could see her face, and how the devil had gotten up all in her, and twisted things around.

Sadie had been wishing Crazy Hattie away, and then there was a pounding on the ground right behind her, and she turned again, and there Hattie was laid flat out, her face all bleeding and Bill sitting on his ma crying and waving Sadie away from there.

If you wished a thing to happen and then it happened, was that your fault? Sadie never got an answer.

She walked a little faster thinking about that, and pretty soon she was down at the bend where her daddy and granddaddy had that big rock fight a year ago, and they hadn’t seen each other since then. Her granddaddy had been walking along there when her daddy came up in the opposite direction leading a cow he’d just bought in town. Granddaddy had said something — he’d said it was just “nice looking deal,” but Daddy claimed it had been “one shitty deal,” and it made Daddy so mad he commenced picking up rocks and throwing them fast as he could. Her granddaddy picked up a few and tossed them back in that general direction, but his arm got mashed up years ago between a crazy mule and the barn door so he didn’t hit a thing. Finally he high-tailed it back the way he came so hard it put his knee out two weeks.

She wasn’t sure Granddaddy always told things exact like they happened — nobody did — and she didn’t much like the way he gossiped about her daddy’s side of the family, but Daddy still oughtn’t be throwing rocks at an old man like that, specially his father-in-law. One of them gave him just a terrible bruise on his left shoulder that lasted three weeks or more.

Sadie heard the noise, turned and saw the old wagon coming down the road toward town. The bank was high off the road here, so she didn’t have a chance to get into the woods and hide.

It was Mr. Mackey racing his wagon team half to death again, with no thought to the life and safety of whoever might be walking the roads this time of day.

He pulled up beside her and stopped, the horses rearing, eyes bulging. But Sadie just walked on by. So he slapped them into a light trot and soon was keeping pace with her. Still ignoring him, she knew that if she didn’t react to him soon he would be staying with her all the way

into town. She kept her eyes to the ground and kept walking,though, needing to keep him going a little longer.

The horses veered closer, and soon she was walking on the far side of the road. Before she knew it the lead horse was grazing her as he trotted. She stole a glance up at his hot, heaving side, the huge and nervous eye. She was about to go into the ditch. The game was over.

She looked up, trying to look more mean than scared. “Get outta my way, Mr. George Mackey!”

The old man looked down at her and grinned. He wore a worn black tuxedo slick and bluish at knees and elbows — from too much proposing, Sadie figured — top hat crinkled a little in front but basically presentable, black ruffled shirt, in his button hole a pressed rose that was beginning to turn brown at the edges.

He pointed toward his big yellow square teeth, lips pulled back like a cow’s to show them off to best advantage. “Goin to the dentist,” he said, “then home.”

“Glad to hear it, Mr. Mackey.” She picked up her pace so that soon she was ahead of the team.

“When you going to marry me, darling?” he shouted behind her.

She turned quickly and screamed at him, “When snakes start milking cows! Now hush up your yelling at me, George Mackey!”

“Why, child, snakes is already milking the cows. Just ask the preacher.” He grinned and Sadie thought that was just the awfullest smile she’d ever seen. A smile like that surely’d kill a baby.

The thought of snakes milking cows with the preacher looking on, blessing the event, made her go cold all over. Her feet began to tingle, as if a snake were crawling under them. She curled them sideways in the dust of the road, but the feeling wouldn’t go away.

“Get away from here, George Mackey!” she shouted, tearfully. “Get away or I’ll have somebody kill you!”

He looked at her then, startled and hurt. Maybe a little afraid too, her being a Gibson and all. He snapped the reins and the wagon pulled away.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

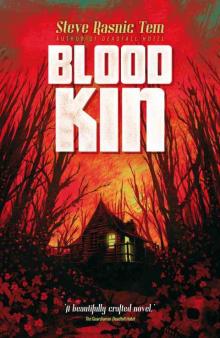

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin