- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

Absent Company Page 2

Absent Company Read online

Page 2

I can see his shadow through the office door. He sits at his desk, apparently reading a newspaper. I step closer, forming my hands into imaginary binoculars. I press against the glass, right below the phrase “Bureau of …” lettered in bold, black characters.

He orders me away from his door. He weeps. He pleads. Now he is shouting obscenities.

I’ve been here … for days.

Crutches

A tap, a thump. A tap, a thump. Michael listened to his mother pacing her room with the crutch, just overhead. He had awakened to the sound, three a.m., and that was two hours ago. Two hours of steady pacing, and how many before that?

He slipped on his robe, trying not to awaken Doris, and climbed the stairs slowly. He paused on the landing, where a great bay window displayed the western slope of the Rockies, the dark houses at its base, and the slow drift of snow like sleep falling from the peak. A narrow road ran between Michael’s borrowed house and those darkened houses, a passageway that held few cars this time of year. A few local vehicles, certainly, but as the snow season reached its height even they would no longer be venturing out. People in Elkins Park took out their cars only when they needed something from another town, or if they were going on vacation. Otherwise, they walked. Or made their way cross-country on skis.

He reached the top of the stairs and looked at the bottom of her door. The light was still on, and now he could hear the tap-thump of her one crutch, although much fainter than it had been downstairs. Once again he blamed himself for dragging his mother up here, but they really had no other place to go. Joe Jensen had offered him the place rent free for a year, just to take care of it, and Michael and Doris had both been out of work for almost two years at that point. And afraid of failing again, Michael thought, then shook himself irritably. Elkins Park did have its advantages—it was cheap to live here, and a quiet place for Doris to do her painting.

There was no energy left in the marriage; there hadn’t been for some time. Lack of money only made it worse. At least sometimes money could buy the energy: concerts, plays, ski trips. They seemed to have no more words for each other. And finally here, in this house, time had stopped completely. They didn’t go forward, but with some relief Michael realized things weren’t falling back, either.

He paused in front of the door, then knocked before gently swinging it open.

His mother stood by the window, grey hair hanging over her cheeks, her tattered housecoat bunched into odd, shapeless lumps; she appeared suspended from the one crutch like a broken scarecrow. A cigarette dangled from the front of her mouth, the long ash suspended impossibly from its tip.

“You’ll burn yourself, Mother.”

She reached up and jerked the cigarette out of her mouth. “I’m sorry,” she said softly, and turned to the window.

Tap thump. A hollow sound, and for a moment Michael imagined that her entire leg was wood.

She had gone downhill fast since the accident. Their first day there she had fallen through a rotten board in the front steps. Michael had thought, momentarily, of suing his good friend Joe, who had no homeowner’s insurance for this old derelict, but his family wasn’t the kind to sue. What happens, happens, as his mother had put it at the time.

She looked awful. The broken leg seemed to have sapped the strength from the rest of her body. He remembered the way it had swollen, so quickly, and even at the time it had seemed the swelling was draining her face, her eyes, her long narrow fingers of their small store of vitality.

“You should try to get some rest,” he said.

She looked at him as if he couldn’t possibly know what he was talking about. Then she gazed out the window again. “I can’t sleep.”

“You look worried.”

She gazed at him distractedly. “I’m going to be on this crutch for the rest of my life.”

“That’s nonsense. You’re healing fine. You never let anything like this get you down before.”

“I was never this old before. I can feel it, Michael. Something’s different inside me. I won’t be letting go of this crutch until the day I die.”

Michael started to speak, but thought better of it. At least she was up out of bed; she’d stayed in bed for a long time after the accident. She wouldn’t even try. Then the town doctor brought the crutches—he said there was a man in town who carved them himself—and she’d pulled herself up on them, so at least she could pace. There was something about the crutches that moved her, pulled her right up out of bed. Michael’d seen the look on her face when the doctor brought them. As if they were arcane objects, mysterious and magical.

“You’re scaring me, Mother.” It was embarrassing to say, but he suddenly realized it was true.

“I don’t mean to, son.”

As he started down the stairs he noted the change in sound. She had taken the other crutch out of the closet and now she was using two.

Tap thump tap. Tap thump. Tap thump thump.

The next morning Michael didn’t get out of bed immediately. His wife was already up, and that made it easier for him to stay in bed. If she were still there in the room she would be able to see he wasn’t really tired at all, and he’d feel too guilty to stay in bed. There was nothing to do. He should have been out looking for a job, he thought irritably, but he knew he wasn’t going to even try for a while.

It was the same every day. The same thoughts, the same worries. The lack of energy. It was the sameness that was wearing him down. He thought it was the sameness that would finally kill him.

The same. Each day. Always. Tap. Tap. Thump.

Elkins Park was a poor place to find work in any case. The general store and gift shop, the trail guide center, were all run by people who had been in Elkins Park for some time. It seemed unlikely there would be any more openings. Most of them had no more on the ball than he did, but they’d got here first and settled. They wouldn’t budge. Jacobs at the guide center was a failed lawyer. Matthews at the gift shop a failed crafts store owner. The gift shop was owned by a friend in Denver and he merely worked there.

Michael didn’t know a single person in town who hadn’t failed somewhere else. The realization troubled him. It was as if they had all gathered here. He couldn’t figure what was so attractive about the place.

The next day he had to go into town for supplies. Willis had had the grocery store in the Park for over ten years. But before that he had had a chain, ten of them all along the Front Range. He’d lost them all in little over two years. Tap. When Michael walked through the door … tap … Willis looked up and smiled wanly. Thump. He had a crutch. Michael wasn’t surprised.

“What can I get for you today, Michael?” Tap tap.

Not wanting to talk to the man, Michael just handed him Doris’s list. Thump.

While Willis was filling the order Michael wandered out onto the wide wooden boardwalk fronting the store. The day already seemed to have turned cooler since the morning. He hunched his shoulders inside his jacket and turned to walk down the street. But he was stopped by the sight of dozens of crutches stacked haphazardly in the alley next to the store.

A bearded man in a checkered shirt lumbered into view, rearranging the crutches into a neat stack. Michael could see now that the crutches looked hand-carved—like the others he had seen around town, like the kind his mother had—each one slightly different.

The big man stopped and stared at Michael, seeming to appraise him, then returned to his workbench set up deeper in the alley.

“Hey, wait!” Michael cried, and ran after him.

The man picked up a rough-shaped crutch and began smoothing it with knife and sandpaper.

“What are you doing?”

The man edged a crutch forward to the front of the bench. “Crutches,” he said.

Michael peered at the man. He could swear there were tears in his eyes. “Everybody needs a crutch now and then, eh?” He wasn’t sure why he said it. “What does a pair cost?” he asked, and immediately regretted it.

&nbs

p; “I only sell one at a time,” the man said softly. “And you don’t seem to need one, not just yet.”

Michael glanced away. The man was grinning now. “You think this a pretty good joke, don’t you!” Michael suddenly shouted, and slammed his fist on the crutch on the bench. It snapped like a twig. Michael’s eyes widened. “Why … why it wouldn’t support a kitten!” he cried.

Tap. The man said nothing. Tap. After an awkward moment Michael turned and left.

He drove home quickly, trying not to glance at pedestrians. But every now and then he couldn’t help looking to the side, and seeing that a quarter of the people were using crutches. Tap tap. Tap tap.

Workers were renovating an old house on the outskirts, just before the turnoff to Michael’s own residence. Hammer shots echoed in the winter stillness. Tap tap tap tap. He tried to ignore the sound. Beams had been propped up against one side; the house leaned precariously, as if the beams were all that held it erect.

One of the workers pulled tools out of a metal box, then tossed them one at a time into the tall weeds behind the structure. Then he sat down on the box, and rubbed his legs.

Michael drove more slowly the rest of the way home, afraid he might miss something. Something was happening in Elkins Park.

When he got home he found all of Doris’s painting supplies in the trash, along with most of her paintings. He picked them out one at a time, sadly, examining torn canvas and broken frames. Some of her best work: that old lady back in the city, her grandfather’s house, Michael’s own portrait.

She was sitting on the couch in the living-room, watching television. “Why’d you do it, Doris?” he asked, feeling uneasy about the trembling in his voice.

“I’m giving it up, Michael. There just isn’t any point.” She looked years older than she had that morning. Tap. Michael was numbed.

“You’ve felt discouraged before …” Tap.

“It’s different this time. I have nothing to paint about, nothing to say.” Tap. “Painting is about the last thing I want to be doing with my time.” She turned her head and locked her eyes onto the television screen.

Michael watched her face glaze over. “So what do you want to do with your time?” He knew it must sound sarcastic. Tap. But she didn’t react. Tap. It was as if she hadn’t even heard him.

Suddenly she was looking up at the ceiling. Examining it. As if she were looking for the point of contact of his mother’s crutch and the floor. Tap. As if she might see the sound. Her eyes out of focus, glazed.

His mother hung over the bed, her hips and belly gone to fat. She glided over the covers and suddenly it seemed to Michael that she was a great dark poisonous spider. He stared at the wall and moaned. It was true—the shadow had eight legs. He turned to see her creeping up over his face, and was almost relieved to see it wasn’t his mother at all, but a small spider made larger in shadow by the porch light, crawling up his bedclothes. But then he looked more closely, and saw that the spider had no legs at all, but eight crutches supporting its fat, limp abdomen.

In the morning, when he opened the front door to receive the mail from the carrier, he saw that the bearded young man was leaning weakly on a crutch. “Won’t be coming out here anymore; they’ll have to replace me. See, my leg here …”

Michael shut the door in his face.

Normally he worked around the house on Saturdays, then read out on the enclosed front porch. But he couldn’t bear to be there that weekend; he couldn’t sit still: Doris with the TV going the whole time, staring at it silently, his mother pacing with her two crutches in hollow syncopation on the loose floorboards. He saw the way Doris watched his mother sometimes now—the glow of excitement in her eyes. Following the movement of crutch, arm, and leg as if it were some sort of ballet. Tap thump. Tap thump. The noise wasn’t very loud, but he found it impossible to ignore. He found himself listening for it, focusing his hearing, holding his breath until he could make out the faint tap tap thump, becoming more and more irritated.

Michael threw down the paperback and got into his coat. He opened the door, hesitated at the first blast of sharp cold wind, then plunged ahead. And almost jumped at the sound of the screen door bouncing off the inner door. Tap tap tap tap. Following him.

He had no idea where he was going. The snow made the road all but impassable; there would be virtually no traffic. About a half-mile before town he looked off towards the Carter place up on the hill. A tiny figure in a red coat, shoveling snow. It looked awkward, crippled. Michael shielded his eyes, squinted, and could just make out the crutch wedged under one arm.

He turned and picked up his pace towards town. And saw someone not more than ten yards ahead of him, standing by the side of the road.

A large bearded man. With an armful of crutches. Michael turned.

Tap tap tap tap behind him.

Michael was out of breath by the time he got back to the house, his lungs almost splitting from the cold and exhaustion. He couldn’t quite see the details of the room once he stepped through the door; the snow had blinded him. But he heard it. Tap thump. Tap thump. With a slight variation in rhythm. Two slightly different rhythms.

He walked into the kitchen. “Hello, son.” His mother’s tired voice. Tap.

“Michael?” Tap tap tap.

As his vision cleared he could see them by the stove—wife and mother. Doris had borrowed his mother’s second crutch. They stared at him. And he couldn’t bring himself to speak.

She woke him up in the middle of the night, every night the next few nights. Tap. Hobbling into the bathroom. Tap tap. Going to the kitchen for some milk. Thump. Letting the cat in. Tap thump. Doris, or his mother—he soon lost track. His mother pacing. Doris moving. Back and forth in the darkened house. The syncopation of their crutches. The synchrony.

Tap thump. Tap thump. No peace. No peace.

After the snow melted that year he was able to walk in the woods again. Until the little boys and girls drove him out. The children were the worst. On their crutches. Breaking their dogs’ legs so they could strap on miniature crutches. Tap and tap and tap in every alley, on every sidewalk. The bearded man made them, as he made all the crutches; Michael had seen him pass them out to the kids. The kids just playing with their pets. But when they ran out of dogs, they started putting even smaller crutches on the cats. Then they were out in the woods, looking for squirrels, birds, anything they could catch, bundles of tiny crutches bunched in their fists like flowers.

Michael stopped pretending to seek work and spent most of his time hiding from his neighbors. He hadn’t been bothered yet, but he was the only one in town without a crutch. It made him uneasy, and now he was seeing the large bearded man and his evil-looking sticks of wood everywhere he went.

Doris certainly didn’t notice; she didn’t notice him at all these days. Unless he stood in front of the TV.

Each night he awakened from a fever dream. Suddenly he was frightened. He could not remember how long he had lived in the town, if he had lived in the town forever, if he would be returning to the city after the summer. If he had ever lived in the city at all. His wife slept untroubled beside him, her shoulders, her shadowed face seeming older than he remembered. Had they been there that long?

He stands up out of sleep and reaches for the bedpost. It is soft wood. Seductive. He pats it. Tap tap tap it replies. Thump. There is energy in the wood. The first energy, the first aliveness he has encountered in some time. And he is so tired, and his life is so much the same, again and again the same. He has no energy.

He runs his hands down the sides of the wood and is soothed by it. He turns to the bedroom window and sees the face of the bearded man behind the glass. Grinning. Tap tap tapping with two stubby fingers against the glass. And amazingly, Michael realizes he is not afraid. He strokes the wood, taps it. It is vaguely comforting and he thinks, tap tap, maybe, tap tap tap, tomorrow it might support him.

The Bad People

Something cold and heavy boarded the bus.

It was a silly thought. He knew that if he hadn’t been having another one of those senseless arguments with Bob the perception would never have occurred to him. As it was, Bob and the intense Mexican heat were pushing him right to the edge. Perhaps that sudden, strange fantasy had been a mental defense, a pressure release valve.

But he didn’t feel relieved. He felt as if he had just done something profoundly evil.

It had been a typical argument with the eight-year-old; he was tired and hot. He wanted to stop now; he didn’t want to ride the bus anymore. He was hungry. He had an upset stomach. They never visited the places he wanted to see. He wished they had never gone to Mexico for the summer.

“I’m bored!” With a savage movement of his hand, Bob pushed the thick black hair out of his eyes, stretched back against the worn bus seat, puffed out his cheeks, then blew out the air hard in ill-concealed anger. Lately, rather than shouting or crying as he had done when Marion was alive, he blew instead.

“I’ve just about had it, Bob.” Cliff leaned over and whispered harshly into his ear, looking around at the other passengers, feeling watched. “You have no choice. We’re going on to Tlaxcala tonight. You don’t have to like it, but that’s what we’re doing. I’m not going to stop every time you feel like it, son.”

Cliff felt a sudden drop in his stomach, a cold, hard sensation creeping in, making his chest tight. He really hadn’t meant to put the nasty inflection on “son”. The whole time his wife had been alive, he’d never used the word. He felt bad about that, but it went too far. Bob had been her brother’s son. He turned around in his seat. A man was watching him from the back of the bus, a tall man with dull black hair—no highlights at all—wearing a dark, soiled poncho. Cliff thought at first the man looked friendly, but then saw that what he had mistaken for a smile was an odd scar across the entire upper lip, curving up at the ends like a wide, shallow “U”. The man’s complexion was a deep amber, almost chocolate, but his hands seemed almost impossibly pale, a white man’s hands, a golden Scandinavian’s. Cliff fantasized the man keeping the hands in ice. He pictured mountains full of snow, travelers lost in the cold and dark, frozen bodies recovered months later from beneath the steep cliffs.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

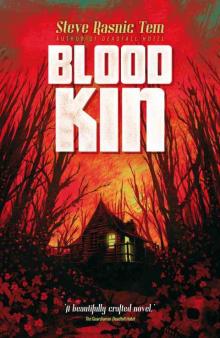

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin