- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

Ubo Page 2

Ubo Read online

Page 2

The area around the building appeared to have been scraped down to bare earth and gravel. Hundreds of yards beyond were the ruins of more buildings, mostly destroyed, not enough left to speculate as to their original appearance. Beyond that a drift of haze, smoke, and flickering talons of flame. Daniel craned his neck to look up at the sky: more, darker smoke, but sometimes there were reddish clouds near molten in appearance. Many days a misty rain came down, and often a steady fall of fine light gray ash.

There was a commotion behind him. He turned, already accustomed to the sound. Several of the enormous roaches had entered the room, their claws clattering across the floor. With impressive efficiency they separated certain men and herded them back toward the arched entrance, the residents hurrying themselves to avoid any contact with the guards.

The morning round of scenarios had begun. They didn’t take you daily, but it was more frequently than every other day. Still, it seemed random, as the roaches never announced their schedule, or anything else. The roaches didn’t speak.

Daniel saw the huge bug headed his way, and ran to stay ahead of it. He did not exactly dread playing his part in these experiments, even though they were often unpleasant. Invariably they were stimulating, and they allowed him to go beyond himself at least for a time, to escape what his life had become.

High drama, excitement, was everything to the human organism.

If not love, then cruelty. If not goodness, then evil.

2

SOMETIMES IT HAPPENED this way. Daniel—non corporeal, a mind in a bubble—hung over the figure below. It was as if he had died, and having left his mortal flesh, paused for a final goodbye.

But he had no idea if he believed that was the way it happened. Probably he didn’t—if the mind of man imagined it, at best it could only be a vague grasping after the truth.

And that figure below was not him, and he was not leaving, but arriving. He was simply reluctant to take the final leap into a stranger’s mind which could only mean more anguish and hellish confusion, and yet another delay before he might get back to leading his own life again.

Not that Daniel had any choice. Behind him was the weight of a thousand mad insects, pushing him to complete his mission, to slip into the stranger’s mind and experience the dynamics behind his violence, however poorly Daniel understood it. The assignment was never that clearly articulated but it was apparent that was what was expected. He made no report—there was no need. The roaches watched everything that happened to him.

He could feel insect parts invading his brain, working their way into his motor centers, into the prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia. The insects, the roaches, had a need to know.

Still, he resisted. He’d gone through dozens of these, maybe hundreds—he really had no idea. Hundreds of personal Hells. He floated, and the longer he floated the more he knew, the more he absorbed from the character he was to play. Mid-Sixties, Austin, the University of Texas. Climbing the tower.Daniel watched as the young man climbed the steps steadily, without rest, arms and legs captured by the precise, military rhythm. This young man was in good shape, and admired precision, and loathed the very imprecise thing that was happening inside his head.

Unable to resist any longer, Daniel was sucked inside.

Going into a personality was much like diving into a pool. You immediately sank to the deepest, coldest, scariest part—the part you didn’t like to think about—before returning to the relative safety of the more manageable surface layers. In this case the deepest, scariest part was the almost robotic, emotionless determination.

Daniel began to sweat more profusely, his heart racing, his legs and lower back straining as he pulled the dolly with the heavy footlocker up the stairs. He saw that he was wearing khaki overalls. He had a vague notion to stop, to get out of this body, this life, to go lie down somewhere. It was hot. But everything had already been decided. Two floors so far, he thought. One more to go. He’d supplied himself well. He was satisfied that he’d done everything he needed to do to prepare for a long siege.

He kept staring at the words printed on the footlocker:

L/CPL. CHARLES J. WHITMAN

USMC - 1871634

Marine Bks.

Navy 115, Box 32-A

FPO, NY, N.Y.

Beneath him, at the bottom of the footlocker, two small, thin arms were straining, wobbling, trying to help him by pushing the footlocker up the stairs. A pale face appeared alongside the footlocker as the little boy put his shoulder into the job. Blond hair so light it was almost white, glowing as if electrified. Daniel had a vague vision of a photograph drifting up out of the inky darkness, eventually floating on the surface: the little boy at two or three, playing on the beach, holding on to two rifles taller than he. They were his father’s guns, C. A. Whitman’s. Guns had always been the old man’s thing—he’d taught the boys how to shoot at a young age, but of course Chuck and his brothers had never been good enough. Well, now guns were Chuck’s thing, and he was far better with them than his father ever had been. Later, after it was all over and the bodies had been carried away, his father would say, “Those guns aren’t to blame for anything.”

As Daniel perspired he felt Whitman’s growing presence in his skin, the sweat spreading from one part of his body to another as Chuck Whitman travelled with it, cooling suddenly, chilling him, and leaving Daniel’s flesh dusty‑feeling, soiled. A strange sensation. Then he felt the thoughts, the desires, the long‑dead rages taking over.

Chuck remembered reading comic books as a kid and thinking how great it would be to have super powers. Maybe you could just point your finger and a building would blow up ten miles away. Or you could look up at a plane flying high overhead and reach out with your mind and bring it down.

But you didn’t need any super powers if you had the right firearm and the necessary skills. You could remove a pigeon’s eye at a hundred yards, stop a heart at five hundred. Add to that the proper stronghold, a fort or a tower, and you could accomplish practicallyanything. Just two weeks ago he and Kathy had visited the Alamo in San Antonio. What those brave men did from that half-assed fort he could do far better from the top of the UT tower. One skilled man could hold off an army from up there, for an indefinite length of time.

He would never say that he loved his guns. His dad probably did—in fact Chuck was sure he did. But Chuck appreciated what a gun could do for you. A gun was the great equalizer. It made you as good as any other man. He felt pretty fabulous about that. What was his was there waiting for him to make the right move. Let somebody dare think he didn’t deserve it.

People weren’t going to understand why he killed his mother. They were going to think that he resented her, that some of his dad had rubbed off on her in some way in his mind, but nothing could be further from the truth. That woman was a saint, and deserved being turned back into energy. Matter could neither be created nor destroyed. It could only be transformed. Looked at in that way, even destruction seemed comforting, simply the means to a greater end. Mayhem had a holy purpose—it could turn you into a superhero, maybe even a god. A God of Mayhem, now that was a thing to be.

His mom was in heaven now, part of the vast source of energy that fueled every human being. Wasn’t that a better place to be than this Hell on Earth?

And he loved his wife, he really did. She was a good person, and he was sorry that she had to work so hard to make enough money to support them both. Over and over he had recommitted himself to treating her better and controlling his temper and not hitting her. He only stabbed her as many times as he did to make sure he got the job done. Better that both his mother and his wife be in a better place of pure energy than to be ashamed of him and what he was going to do that day.

“Can we rest?” the little boy pushing the footlocker whined. Chuck hated whining and he hated the scrunched up face the boy made when he whined.

“No. We’ve got one more floor. Then we’re going to do what we planned to do. Don’t be a quitter, boy. I�

��ll throw you down those damn steps if you quit on me.” The boy didn’t say anything but he went back to pushing the footlocker up the stairs. Chuck rubbed the back of his neck. The crisscross of insect scratches like stitches in his skin ran straight up his neck and across the back of his scalp. The sweat oozed into the scratches and made them burn like his head was on fire. He pulled out the white bandana and tied it around his forehead. It would keep the sweat out of his eyes so he could shoot better. He tossed a second bandana to the boy so they would match. He was feeling impatient now but he waited while the boy fumbled with it and put it on. He had it on crooked but there was no time to fix that now.

Chuck’s shirt was soaking wet. He probably stank by now. He’d put some spray deodorant into the footlocker but he couldn’t take the time just then, so he reminded himself to use it later. He also couldn’t take the time to make an actual physical note about it so he hoped he would remember. He’d been very distracted lately.

He hoped that later, when they wrote about it, they’d put down that he’d been an altar boy. Also that at 12 he was the youngest boy in the country to make Eagle Scout. That was important. Maybe he’d have time later to write that down in a note. And maybe he should mention his piano playing.

Of course he’d wanted to be more. He’d wanted to be lots more, but sometimes you have to work with what you’re given. Thank God he was a great shot.

He didn’t have to worry about a job anymore, or good grades, or what his mother wanted today, or what his father would say, or if he could be a good enough husband to Kathy or not.

And Kathy, she’d been Queen of the Fair in Needville, Texas. Maybe he’d write that down, too. Probably the prettiest girl around.

Hated his father, of course. Old C.A. Maybe he’d put that down, just to make sure they knew why he was probably doing this, even though he wasn’t completely sure himself.

“Hurry up, boy!” he shouted down to the kid. “We’ve got a schedule to keep! Don’t you dare make me late!”

Daniel came out of it for a second. Had Chuck almost passed out? The stairwell was empty, cold. But there was still a kind of ghost here, a memory that was more than a memory. Chuck Whitman was a ghost of a memory that still haunted this place. He’d left his stain behind in the air.

Daniel felt insect legs scrabbling, an oily smell as they tried to regain control. Mandibles clicked against his flesh damp with a cold sweat. The ghost drifted in and out of his skin as his breathing grew ragged. Daniel became more excited as Chuck—large and again in charge—re-exerted himself and marched up the steps of the tower.

Daddy had been a self-made man. Chuck had wanted to be, had started out to be, but Daddy just couldn’t leave it alone, couldn’t stop picking at him. Not that Chuck didn’t want to be perfect—he just had to get there his own way.

“Pick it up! Pick it up!” he shouted at himself and the boy struggling to lift the end of the footlocker. They had a schedule to make. “Don’t make me throw you in the pool!” Chuck had just turned eighteen when Daddy did it to him, for celebrating drunk. Chuck’d almost drowned. Sometimes he thought that would have been a better way. But you go with what you’ve got. Chuck knew he was going to be famous for doing a terrible thing. Imagining the press grilling old C.A. about what his son had done made Chuck smile.

He had to get that receptionist out of the way before he did anything else. A rifle butt to the back of her head and a crack across the eye put her down so he could drag her behind the couch. That couple came down from the observation deck while he was standing by the couch. The surprise of it shook him a little, but then they left—they hadn’t seen anything. He barricaded the stairway. The boy kept jabbering at him about more people coming up.

Chuck took the sawed-off 12 gauge and shot the two boys trying to open the door. Then he fired a few more times through the grates at the other people. He was annoyed—none of this was planned. He barricaded the door to the reception area. He started out onto the observation deck, stopped, walked over to the receptionist lying behind the couch, took aim and shot her in the left side of the head.

He was proud of how well he’d outfitted his footlocker. He could hold out for two days easy with all those supplies. As he went through the items and laid some of them out the boy got more and more excited, clambering around like a monkey until Chuck had to give him the back of his hand. That shut the boy up some, made him move a little more cautiously, but clearly he was no less enthusiastic than before.

Chuck’d packed that Randall knife with his name on it, a Camillus hunting knife and the Nesco machete in its scabbard, and even a hatchet, if it came down to it. It would take him at least a couple of days to go through the 700 rounds of ammunition he’d brought, but then they’d send somebody to pull him off the tower unless they decided to blow up the tower with him in it, which would be spectacular, but foolish and unlikely. Maybe they’d even send some fellow Marines in to do the job. Then he’d have to go at it hand-to-hand. He wasn’t as good with a blade, but a knife fight made a cool picture in his head.

He pulled out the Channel Master 14 transistor radio, which would be handy for monitoring the response by the local authorities. Notebook and pen, in case he needed to leave any more notes. Light green towel, white jug of water, red jug of gasoline, rope and clothesline, and that terrific Nabisco toy compass he’d sent away for when he was thirteen. Of course the boy snatched that up right away and Chuck had to snatch it back with a scolding.

Canteen, binoculars, matches and a lighter with extra fluid. He had a vague idea he might have to turn the gas jug into a bomb but wasn’t sure if he could do it right. Anyways now would be a good opportunity to try that out.

Alarm clock to wake him up when he needed to rest, pipe wrench and flashlight and two rolls of tape, gloves and earplugs. Also that Mennen spray deodorant—he didn’t know whether he should use it now or not. He just didn’t want people saying he’d smelled bad. The boy picked up the toilet paper and started running around the deck with it. Chuck wondered if he might have to throw the boy off the tower at some point.

He wasn’t sure if he had enough food. He’d brought twelve cans of it, plus a couple cans of Sego condensed milk, bread, honey and Spam, some sandwiches he’d already made, Planters Peanuts and raisins. Sweet rolls. But maybe he’d be way too busy to eat.

And of course he had a goodly selection of firearms. His favorite was the scoped 6 mm Remington—that’s what he was best with. He’d also packed a 700, an M1 carbine, .357 Magnum, Luger, and a Galesi-Brescia. He hoped to use them all, but you never could tell. You had to stay flexible.

He was feeling more mellow now that it was almost time. He placed his hand gently on the boy’s shoulder and guided him around the deck, explaining to him how they were going to go from shooting station to station, firing a few times from each so that the people below would think there were more snipers up on the deck than just the two of them.

Back at the starting point Chuck looked at the boy and nodded. Then he raised the Remington, gazed down the scope at the figure crossing the South Mall of the campus, let go of his breath and pushed back the trigger. He expected to feel something—excitement, elation, completion—but he felt nothing when the girl fell. Then he shot the fellow leaning over her.

He aimed for the center of the chest with each one. He didn’t want to risk missing with a head shot. He moved his targets east, to the Computation Center. He glanced at the boy, dressed identically to him with his white bandana and brown khakis, also shooting from the rainspouts around the deck. Chuck went westward and sighted along Guadalupe Street. He shot a fellow off a bicycle and started checking out the store windows. He shot somebody coming out of a newsstand, someone else hiding behind a construction barricade. He was perfection at last.

Suddenly people were shooting back at him. He peered through one of the rainspouts—he saw Texans hiding behind trucks and cars, rifles raised, firing his way, chipping the concrete all around him. It was just like the Alamo.

He almost laughed. All them good ole Texas boys, taught by their fathers from an early age how to use them guns. He switched to the carbine and returned fire. Killing America, one bullet at a time.

He heard the drone of the small engine, looked up in amazement as the small plane approached and a man leaned out and opened fire. King Kong all over again. Chuck shot back as if he was waving off a mosquito and the plane retreated.

He shot a few more figures, maybe—now he wasn’t so sure. Before he was like God raining down bullets. Now he was just struggling to take back control. It was proving harder to get off an accurate shot. But on the south side he picked off someone who had stood up behind a car.

Maybe if Daddy had just spanked him more. Some of them would say he got off easy. He’d kept telling himself to be gentle with Kathy. He’d written it right down in his notebook:BE GENTLE.

He tried to let everything leave his head. He had nobody left to worry over him, nobody left he owed a thing to. There was nothing he need worry about anymore. Finally, he could escape himself. Erase himself.

The people down there, they had no idea. They had no idea as to whether they were safe or in danger. They had no idea of his range.

Someday people would just walk down the street, and they’d have a hundred different rifles pointed at them. Someday that’s the way it was going to be everywhere.

Two men ran into range, Chuck tracking them. He missed the first, and the second jumped out of range before he could pull the trigger again.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

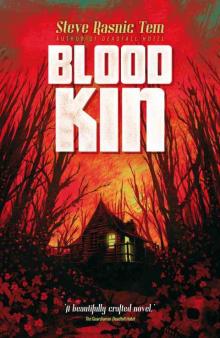

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin