- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

The Man on the Ceiling Page 2

The Man on the Ceiling Read online

Page 2

Veronica has the biggest heart of anyone I have ever known. But the fear she has carried around since she was a little girl, despite our sometimes desperate efforts to heal it, threatens to destroy her time after time.

Gabriella and Joe do well despite their struggles, but they must live with dreams of a birth father who broke his children’s arms and fractured their skulls in his fits of rage, and a birth mother who did nothing to stop him.

And Anthony is dead. And we will never know for sure if it was the madness of his first four years that finally caught up with him and ripped him from our lives.

But for just that moment my family was safe, sleeping in their own particular ways. They dreamed of things I was not privy to, but they were safe. All I had to do was pay attention and keep that car on the road.

But you never know what’s going to happen on a road trip. You can’t always anticipate what you’re going to run into.

And the number of desperate children gathering outside the car continued to grow. There’s no room, I wanted to tell them. It’s all I can do, I might have said, but how could they possibly understand? I looked in my rearview mirror at the other cars, praying they would stop and pick up just a few of those children. But there were so many. You could not begin to imagine them all.

Chapter 2

Alchemy

Imagination transforms one substance into another. It changes what is into what might be, what was into what might have been. Straw becomes gold, gold straw, and neither is more real nor, I submit, more precious than the other. Pebbles turn into luminous pearls and pearls into little gray rocks, both solid and beautiful, both essential. Human beings take shape from clay, angels’ wings are spun out of water, fire gives rise to the long tongues of demons, love emerges out of thin air, and the basic elements reconstitute themselves again and again.

Like other powerful tools—language, nuclear energy, genetic engineering—imagination carries risks. If I had imagined my children too vividly before I became their mother, I might have missed who they were and how they would reveal themselves to me. As they grew up, I tried to resist imagining the best or the worst for them (which is to say, my version of the best and worst, not theirs), lest anticipation or worry interfere with meeting them where they were rather than where I hoped or feared they might be.

Anthony did not grow up. One spring evening when he was nine years old, he hanged himself from the post of his top bunk bed with the rope he’d been using earlier to walk the dogs.

I would have imagined that to be unimaginable. Sometimes I still do.

For a while after Anthony died, I sought out the company of other bereaved parents, desperate to immerse myself in their stories and my own. I noticed how the stories often became litanies, told with exactly the same words in exactly the same rhythms:

“When she called to tell me about the accident, we thought it was her son who’d been killed, but it turned out to be mine.”

“I knew she was gone before they told me, because her little ears were blue.”

“It was the middle of the night when the knock came at the door, and I knew right away that our son was dead.”

“When I called him for dinner he didn’t answer, and I thought he’d fallen asleep, so I asked Steve to go in and wake him up.”

I was struck, too, by how imagination rushes into the miasma of acute grief and does its best to make sense—any kind of sense—out of something not so much nonsensical as a-sensical. Perhaps the need to impose order at almost any cost is primal; perhaps it serves some evolutionary purpose. Any explanation was better than none. In our desperate circle, we created our own myths, which might or might not have been constructed around objective truth, and clung to them even when they caused us harm:

“The school should have known this was going to happen.”

“The doctor didn’t catch it soon enough.”

“If I’d had dinner ready earlier that night, he wouldn’t have done it. Five minutes earlier.”

“God is punishing me.”

“God has broken His word to us.”

Was it careless play or suicide? Anthony was not a depressed or angry child; in fact, of all our kids, he was the least volatile. But he had been mad at us that evening because we wouldn’t let him go to a friend’s house, and he had been horribly abused and abandoned during his infancy and early childhood.

If it was suicide, did he know what he was doing? Is a nine-year-old capable of imagining the finality of death?

Is anyone?

I am. Now.

Knowing the “how” of my son’s death became urgent, and my imagination supplied one scenario after another. He’d been playing “doggie” and had slipped off the top bunk. He’d been thinking, with a child’s logic, “I’ll kill myself, and then they’ll let me do what I want.” Early trauma had come home to roost.

But the truth is, we’ll never know what happened that night or why. And it wasn’t until I surrendered to that hard un-knowing that the grief could begin to flow freely. It’s still flowing.

So imagination can obfuscate, constrict, trivialize. Imagination can keep us from knowing what’s true.

But sometimes imagination is the best or the only tool available to us for apprehending truth. Before I loved my children, before I met them—before I knew about how Chris would hold my hand when I thought I was going blind, how Veronica would race down a long sidewalk to jump into my arms, how Joe would come and get me to show me a rainbow, how Gabriella would call me “Mommy” well into adulthood, how Anthony would cock his head to the right and sing me a song—before I knew my children at all, they were my children, because I imagined they were.

I did not imagine my children into being. What I imagined—what would not have existed had I not imagined it—was being their mother. I was their mother before we ever knew each other, and they were my children, because of the alchemy of imagination.

It couldn’t have been any other way. Some fundamental truths are accessible to us only through imagination. It’s magic, and it’s as real as it gets.

Usually imagination goes forward. But there’s also a form of imagining that, for its own purposes, possesses things from the past.

Everything can be possessed, and has the power to possess. There are places that after-shadow the past in much the way the future can be foreshadowed—viscerally, with evocation rather than precision, inviting us in to imaginative participation. They come to us through time and space and dimension, demanding—what? Attention, at least. Creative and truthful use.

Increasingly throughout my adult life, I’d had visions of the place of my girlhood. Flashbacks, memory fragments, summonses, breakthroughs from another dimension—I never knew what to call them, and I didn’t know whether other people also experienced such things. Vivid, highly sensory, plotless and without characters, they seemed to be about place.

These visions would burst into my consciousness at moments that seemed entirely random and in no way connected to their content. I’d be doing my motherly duty helping one of the kids with algebra homework, and suddenly white fence blue spruces little marshland along the road, the side yard of the house where I grew up and then I’d snap back into the present with the sullen child at the dining room table, evidently not having lost any time or space in this reality.

Or, I’d be absorbed in a fascinating lecture about the Anasazi or riparian ecosystems, and the purple music of a harmonica on a summer’s night from the dark porch on the other side of the screen that smells faintly rusty where I press my face against it and close my eyes knowing my father is playing but believing the music has no source then I’d be back in the classroom with the professor at the same point in the same sentence as when I’d left.

I’d be writing case notes or cooking dinner or watering plants or making love or learning to ski, and my room when it had gray walls and lavender curtains, the plush of the lavender rug under my bare feet and then I’d be back and nobody, apparently, would know I’

d been gone.

There was an urgency about these visions, but no foreboding. There seemed to be something important in them, but not something dreadful. They didn’t frighten me, but they called me, compelled me, though I couldn’t figure out why.

The sign says “French Creek Drive,” but it’s wrong. This road where I grew up does not have a name. “A mile north of town on Route 19, the first dirt road to the left past the gift shop that sells goat’s milk fudge, the only house on the left-hand side.” The directions come back to me like a jump rope chant.

Despite the sign, I know where I am. I step off the asphalt of Route 19 onto the gravel of the shoulder. A row of ten or so mailboxes used to stand right here, gray metal on splintery wooden poles. Some were shaped like loaves of bread, others like bricks; my family’s was like bread. If there was mail, the little metal flag would be up. If it wasn’t up, I would check anyway, as much for the ritual of pulling down the stiff-hinged door and reaching into the dusty interior and losing my breath to the wakes of trucks barreling south as for the chance of a letter.

There are no mailboxes now. Adult perspective tells me the poles must have been sunk in concrete; neither my eye nor the scuffing sole of my shoe locates evidence of it, and I wonder if there’s any under ground. I wonder how the people on French Creek Drive get their mail. Probably they drive into town to the post office. I’d like to know the smell of the post office, the arrangement of the boxes, likely conversations with the postmaster behind the counter, how many steps lead up to the front door, what time of day sun reflects from the windows and glass door. Maybe I’ll stop by the post office when I’m done here.

I wouldn’t say I’m frightened. There’s nothing to be afraid of here. But the state I’m in does resemble fear—heart pounding, hands shaking, the intense dual sensations of being summoned and of being warned away.

Pledging not to tell myself stories until I’ve received whatever stories are already here, I set out.

Mrs. Sandbach lived in the first house on the right. I don’t remember Mrs. Sandbach, only the name and the house set back from the road in a swampy little bowl. The house is gone now. The ground is still soggy, grass so thick and green-black it might be rotting where it grows. I don’t even know how long Mrs. Sandbach lived in this house, when and why she came here, whether it gave her shelter or entrapped her, who ever lived here with her, when she moved or died. I think she died. (Of course she died. She was old then. How old, though? Old in relation to whom? I don’t think I ever met Mrs. Sandbach, which is startling.) As far as I am concerned, Mrs. Sandbach always lived here—”always” meaning “all my life,” “whenever I took notice.”

Apparently our lives intersected for a substantial period of time and space, and did not intersect at all. Unless I was a part of Mrs. Sandbach’s life without Mrs. Sandbach being a part of mine. Unless Mrs. Sandbach noticed me. Wondered about me. Watched me going for the mail, waiting for the school bus, running from the mean red dog the neighborhood kids had happily demonized to provide the only danger I was ever aware of growing up.

The possibilities are arresting, along with the realization that I will never know. Standing here at the side of the nameless road, looking at the empty lot, I could make something up. But the story I’m being summoned to and warned away from isn’t here, and whatever I made up would not in any sense be true.

The nameless road curves to the left around the line of tall feathery poplar trees that edged our yard until the year they all died at once—poplars, my father explained grimly, have a short life span—to be replaced by their own ragged stumps. This yard-edge figures strongly in my dreams, daydreams, flashbacks of this place. It’s still the only house on the left-hand side, but it’s not edged by anything now, no boundary between yard and road. The curve of the road is much shorter than I remember it; I’m around it in much less time. I know not to look yet to the left. It’s not time. I’m not ready. I’m not ready.

To the right, off the outside bow of the curve, lies a land shrouded not in Mystery but in lowercase, pleasant, unobtrusive mystery. No intimations of danger or transcendence; my reluctance to go down there has to do with run-of-the-mill worries: I don’t live in this neighborhood anymore, and I no longer know where borders of private property are and which ones it’s permissible to cross. I would feel self-conscious doing now what once I did freely day after day after day. Out of place.

From the gravel and mud at the outer edge of the road’s curve, I never could see down into the little enclave over the hill, and I can’t now. There was a dark brown house in a hollow, and a loose-planked bridge over a rivulet that must have been a tributary of French Creek. A settled place. With no idea who ever lived there, I could make up all sorts of true stories set in that imaginary place, and maybe someday I will. But not now. Now I turn and go on, not looking left.

The Erskines are all dead. Except maybe Bill, Sr.; he’s almost certainly dead of old age by now, but I haven’t heard about it. Marie, Carole, and Billy have all died of cancer. Maybe Bill did, too.

This knowledge is not new. Carole must have been in her late twenties when she died, and her mother Marie didn’t survive her long. I, away from home by then, am not aware of a moment before which I did not know of their deaths and after which I did, although there must have been one.

Billy and I used to listen to cowboy music on his little record player while our mothers chatted on the Erskines’ front porch. I used to wonder about Carole, who was older and obese and unpleasant. Marie seemed to cry a lot; I used to wonder about mothers who would weep in that soft, seeping way.

One early-adolescent summer evening, Billy and I sat on my family’s picnic table with our feet on the bench, roasting marshmallows in the outdoor fireplace and talking about life. This was the only real connection the two of us ever made, and I’m not sure now how real it was. Real or not, it didn’t lead anywhere; we had been childhood playmates solely because of the happenstance of geographic proximity, but we were never friends. I felt no personal loss when he died a few years ago, only an eerie sort of vertigo. Someone sent me his obituary. Small-town newspapers still list cause of death.

Our two families lived just across the road from each other for decades, sharing the same time and place, and I see now that we hardly knew each other, didn’t occupy the same place at all. Someone else lives in their house now; there’s an SUV in the driveway and a boat in the open garage. Positioning myself to be mostly hidden by the lilac hedge if anybody’s looking from the house, my back resolutely to the space where giant blue spruces have, incredibly, been removed from the yard where I grew up, I regard the Erskine house and wonder what it hid then and what it harbors now. Nothing comes to me. Anything I come up with would be out of whole imaginative cloth. After a while I simply move on.

As far as I know, nobody ever even spent the night in the tiny cabin on the creek bank, scarcely larger than a child’s playhouse. A few times a year someone—I remember the first or last name Alden and I think maybe he came from Pittsburgh—parked in the truncated driveway, mowed the weeds, and was gone before the sun went down. Although I never saw him arrive or leave, there’s no particular mystery about this. It was just a cabin in the country that Alden never used but was obligated to keep up.

But why didn’t he use it? Why didn’t he sell it? Who was Alden, anyway? How could I have spent my entire childhood across a narrow dirt road from this place and not have known anything about it?

I make a mental note that there might be stories here worth telling. But not today. For me, this little house is not haunted, just empty. I’ve never been inside it, have no sense of the place it contains and creates, and I’m content to leave it at that.

The Browns lived in a brown house. This wordplay made corporeal was a longstanding source of delight to me, the child who lived down the road. My house—long and low like a train, wider than it was tall so that living in a house taller than it was wide became a symbol of emancipation for me—was sometimes pi

nk and sometimes pale green, its color in no way representative of my rather more complicated surname.

Judy Brown was slow. My parents said so whenever Judy’s name came up, their voices and faces limned with sympathy and disgust. At the time I didn’t quite understand, but now I do remember a certain slowness about Judy, a certain crudeness that seemed to come from simple-mindedness, though it’s possible that the memory is really of what my parents said and how their mouths twisted and their eyes cut away when they said it.

There was also something else about Judy, a quality that from the perspective of more than forty years seems to have been wild and joyous, and also hurt, hunted, fearful. As a child I wasn’t very good at interpreting facial expressions, but Judy’s face would sometimes take on a certain look, her body a certain stance, and I would feel afraid. Not ever afraid of Judy herself, but of what Judy was afraid of.

Judy’s brother Buddy was slow, too. He was older. He never rode the school bus. I seldom saw him and never up close, but I knew his skull was pushed in just over his left ear, twisting his whole face; I never heard the story of how that happened to him. When Buddy’s name came up, which couldn’t have been more than a few times during my entire childhood, something happened in my parents’ voices and faces and bodies. Something bad. Something tantalizing. Stay away from him, they warned me, and I did, but I took it as evidence of intolerance and lack of compassion and held it against them for many years, until well after they were dead and things began to fall into a different place.

With long ragged dark hair and a wide mouth, Judy was pretty in a way I recognized even then as coarse, though I wouldn’t have the adjective till much later. Judy’s stop was next after mine on the school bus route. Flouncing into the seat behind me as if it had been saved for her, she’d lounge against the window with her feet up in what seemed then like wild abandon. One morning she bestowed on me a little blessing. Reaching suddenly over the seat, she touched the mole on my left earlobe and in her loud, rough way pronounced it a beauty mark. And so it was, and so it still is, and when I put in an earring or brush back my hair I smile to think of the kindness of Judy Brown, which has lasted a lifetime.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

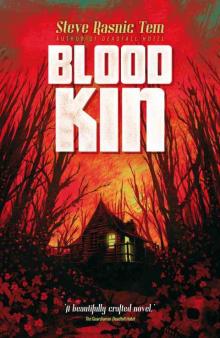

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin