- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

The Book of Days Page 3

The Book of Days Read online

Page 3

“Mizz Dinkens?” the sheriff called out. “Where yore husband be?”

The old woman started laughing. “Oh, you want he should stop me, is it? Man like you, he thinks a husband stoppin’ his wife is in the blood as well. That man beat me most of my life and you knew about it– I told you about it– an still you did nothin’. Suppose you thought it was all right an natural. I suppose you thought it was all in the blood. Well, I reckon I got some say about that, even if I be a poor old woman. I got some say. I had me enough, I had me enough fer a hunderd women. That old bastard! But that’s the lot of you men in this town: old bastards! Old bastards in the blood!”

“Where is he, Mizz Dinkens?” the sheriff asked again.

“Why, sheriff!” Old Mizz Dinkens laughed and winked, and made a little, somewhat provocative dance. Then she pulled out another Mason jar full of blood. And then another. And then another. Smashing them to the pavement, splattering blood on the bride’s dress, throwing it high and slinging it over the heads of the crowd. “I thought you knew! Old Elmer, Mister Elmer Dinkens– he’s in the blood!”

SEPT. 13

1876: Sherwood Anderson, author of Winesburg, Ohio is born.

1971: New York state troopers crush a prisoner revolt at the Attica State Prison.

The bench between the post office and the town jail was the best place for people-watching. Sooner or later everyone in the community would pass by.

He wondered if the jail here was typical of small towns. Home-cooked, buffet-style meals were brought over in covered dishes by Minnie Hatcher and her teenaged sons. Special requests were frequently honored and an occasional treat for later might also be supplied. Sometimes she and the boys even stayed around to chat before taking the dirty dishes back to the house. The woman had an older daughter, but she wouldn’t let her participate in any of this, afraid “she might get a hankerin’ for the wrong kind of fella.”

The regular prisoners (drunks, mostly) put out a folksy newsletter with a circulation of a dozen or so. The deputy had his girlfriend at the clerk’s office photocopy the one-pager and it usually showed up on bulletin boards and store windows around town. Full descriptions of favorite meals were given a prominent position, although once the sheriff had censored the paper when a rum cake was mentioned.

This particular evening one of Minnie’s boys was sitting on the ground near the bench. A young man not much older, in gray jail coveralls, was sitting beside him, a deepset frown creasing his face. “But you gotta go back, Elmer,” the boy said with an anxious glance at the jail. “They’ll figure out you’re gone pretty soon.”

“Ain’t goin’. Damn deputy called me a criminal. Said it right in front of yore ma. What’s she gonna think?”

“Well, Elmer, Christ, you are in jail, you know?”

“That don’t mean he can say whatever pleases him. What kinda manners is that? Didn’t he have no momma to teach him right?”

“Come on,” the boy pleaded. “Jail breakin’ is a serious offense.”

“Hell, I didn’t break nothin’. Just followed you out the door, is all.”

“But, Elmer. Jailers, they don’t see that just as walkin’ out a door. They call that ‘jail breakin’, ‘bein’ on the lam.’ And I hear tell they take a pretty damn dim view of that kind of activity.”

“That deputy apologizes, then I go back in there. Not before.”

“You’re gonna get me in trouble. They’re gonna think I was in with you.”

“Why, don’t worry none, Bobby. I’ll just tell them I masterminded that whole damn escape. Hey! I’ll tell them I took you hostage. Howzat? Get your name in the paper I bet.”

That was when they saw Cal standing there. Bobby’s face turned red and he gazed down at the grass. Elmer started whistling, looking up at the sky.

“I couldn’t help overhearing,” Cal said softly, ready to run if the need arose. “I think this young man was giving you some pretty good advice, if you don’t mind my saying.”

“Hell, I don’t mind. If I knew what I was doin’ I wouldn’t be in that place, I reckon. Hell, if I knew what I was doin’ no piss-ant deputy’d even think about callin’ me names. Set a spell, why don’t you?” And he gestured toward the bench.

Cal sat there for a time, staring at the ground while Bobby and Elmer stared at the sky, staring at the sky while Bobby and Elmer stared at the ground. This pattern was eventually broken when an angry Minnie Hatcher stormed into the small grassy area. “Bobby Hatcher! Get that prisoner back into jail this instant!”

“Ma, it wasn’t me!”

“That’s right, Missus Hatcher,” Elmer said sitting up straight. “I was the one what masterminded it.”

Mrs. Hatcher looked down at him. “You’re a grown man, or should be. You should know better, getting my boy in trouble.”

“Well, see, ma’am, that deputy insulted me and …”

“Lord, Elmer, you’re in jail! I’d think a little insult’d be the least of your problems.” Then she glanced at Cal. “Well, howdy-do, Cal. Heard you’d moved into your momma’s old place. I surely apologize for these two youngsters. Being a parent’s hard, but I’m sure you know about that.”

Cal’s belly tightened. Elmer looked at him. “You a daddy?” Cal nodded. “Well, you look like an educated man. My daddy, he weren’t so educated. If he’d been educated, he might have taught me better.”

“Sometimes,” Cal said. “A daddy doesn’t even know whatever it is he’s supposed to teach.”

“Well, see now? That’s even daddy thinking, that is. My daddy couldn’t do none of that. Me, I feel at home in jail. I get so nervous outside I can’t wait to do something to get myself back in. Else I’d be long gone from here by now. This weren’t really no breakout, don’t you know– just wanted that deputy to pay attention.”

“Hold it right there!” A shout, and everybody turning.

A handgun exploding.

Cal saw the deputy not more than ten feet away, the image shaking because Cal’s head was shaking. “Jesus!” Elmer was holding his chest, but there was no blood. The shot had missed. Elmer looked down, rubbed the cloth of his shirt. Cal wondered if even the deputy knew whether he’d meant to shoot Elmer. “Jesus!” Mrs. Hatcher exclaimed again. “Put that gun away.”

The deputy was trembling, the handgun– held out fully extended with both his hands on the grip– waving back and forth. Cal backed away. Elmer stared at the deputy, then let his hands down. Bobby was crying like a baby. His mother went over and put her arm around him.

“Hold it, damn it! Hold it, I said!” The deputy walked forward, the gun still pointed at the small group. “Walk toward the jail. Slow.”

Elmer did what the deputy said.

SEPT. 14

1927: Dancer Isadora Duncan is killed in France when her scarf catches in an automobile wheel.

The world was full of long, deadly, treacherous scarves.

That’s what drove parents crazy. There was no escaping it. When the kids were still small Cal and Linda had had neighbors whose two-year-old son had strangled himself on a curtain cord. These people hadn’t been bad parents, but they would forever feel as if they were.

A girl a few blocks away had opened the rear door of a school bus and tumbled out onto the pavement, receiving serious and permanent injuries. The father told Cal he must not have taught his daughter enough about the world, about how things worked, otherwise she would never have done such a thing.

Some years it seemed that all over town children were falling out of open windows, falling out of the backs of trucks, falling off the tops of playground equipment, losing their hands in machinery, riding their bikes downhill into rush-hour traffic.

Linda had a cousin whose son had died driving drunk. He’d been a smart, perceptive kid. He’d surely known better. But he had to find out for himself. Some things children learned only through trial and error, and one could only hope the natural consequences were lenient. A parent could talk all day and the child might ev

en listen, might even understand.

And a mother, a father, couldn’t do a damn thing about it. The world was full of treacherous scarves, and you couldn’t find them all and hide them. It was impossible. It was unbearable. And so Cal had run away. Surely Linda could handle the state of the world better than he.

“Daddy, you’ll protect me, won’t you? Forever?” His little girl had actually asked him that one time. And with tears in his eyes he had said yes. He had lied to her. And she’d asked him what was wrong and he couldn’t tell her, nor could he lie to her again, so he’d gone outside and sat under a tree and cried as if his heart were breaking. And there were all these branches and bits of ribbon and clothes out there she’d left from her play. And he’d thought they were snakes, and he just had to collect them all and burn them and if he could then she’d be safe. But he couldn’t tell which were truly dangerous, which were the snakes and which were things she loved to play with and would miss terribly if he got rid of them. And so he’d sat there until after dark, impotent, unable to do a thing until Linda had come out and found him there.

SEPT. 15

1917: the US government takes control of the sugar industry.

The biggest fights of his married life were over what foods and/or chemicals should or should not go into their children’s bodies. Cal would read an article in the paper and suddenly he would want to ban red meat from their table, or bacon, or eggs. Linda had always had a thing about sugar, and watched their children constantly for signs of hyperactivity, read every book on the subject, watched every television show. Cal agreed in principle, but his own memories of candy and its place in his childhood made him feel that his kids would be missing out on too much of a collective American childhood experience if they banned candy from their home.

Every week a different food or food additive was accused of threatening the well-being of American children. How were they supposed to know what to put into their kids’ mouths? He supposed it had been easier in the old days, when a bad food was simply one that had spoiled or gone rotten, and sometimes not even that.

Somewhere even as he thought about these things, he knew a man in a dark coat was giving candy, and substances not easily identified, to children on a school playground, children in a park, children right under their parents’ noses. The children would eat these things and smile, and those smiles might change their lives forever.

He could never see the man’s face, but sometimes he thought it must be very like his own.

SEPT. 16

1885: psychoanalyst Karen Horney is born. Revising Freud, she stressed security needs over sexual and aggressive drives, and argued that people are always capable of growth and change.

Cal watched two children on the town playground. A little girl pulled a toy truck away from a little boy and began hitting him on the head with it. “Go to work, you lazy bum!” she screamed.

The little boy looked at her in stunned amazement, then began to cry. “I’m sorry! Our kids are going to starve!”

She came over to the boy and started petting his head as if he were a dog. “There, there. There, there. Our kids won’t starve. I’ll get a job as a movie star! I know, you could be my manager!”

The boy looked at her, obviously relieved. “Our kids won’t starve?” The girl nodded solemnly. “Could I do the cooking?”

“Sure!” the girl laughed. “I cook yukky stuff anyway!”

The boy went to get water to make some mud pies. The girl picked up a large rock and beat the flimsy truck over and over until it was completely unrecognizable.

The boy came back with a small plastic pail full of water and stared at his beaten truck, a worried look on his face. “Oh, I see,” he said. “You found a thing!”

“Yeah!” The girl giggled. “I found a thing!”

The little boy and the little girl hugged each other and used their new-found thing as the centerpiece for their dining table of sand.

SEPT. 17

1883: Poet and physician William Carlos Williams is born.

THE SANDBOX

(for my children)

I would give you this

sandbox upon the planet

whose pail and shovel

fill and empty

the planet

with children’s play

with children’s hands

and feet digging

the sand of the planet

rising and falling

to fill and empty

again

and again the planet

with little progress

and no sense

of completion

but that,

my sandbox children,

my children of sand,

that is the best part.

SEPT. 18

1933: Ghazi I crowned King of Iraq.

Because he was the king, he need not answer to anyone. This seemed quite an advantage his first few months on the throne. If he wanted ice cream for breakfast he simply ordered it, and his loyal retainers made it so. If he wanted to go to the theater a night when plays were not scheduled, there were actors just waiting for his call. If he wanted sunshine at night and darkness in the daytime, there were people he could go to and get the thing done.

“But, Daddy, I can’t sleep now,” his princess complained, and the king had darkness and light returned to their proper places.

“But, Daddy, you promised you’d help me with my homework,” his prince complained, and the hastily-arranged play performance was canceled.

“But, Daddy, ice cream for breakfast might kill you,” his prince and princess said tearfully in unison, and the king was reduced to eating cereals and juice.

During the second year of the king’s reign he made his children official advisers on all matters relating to the royal household and his own behavior.

His children told him how excited they would be to one day grow up to become king and queen, because then they could do anything they desired.

The king merely shook his head and attended to his official duty: worrying long into the night over the continued health and happiness of his young king and queen.

SEPT. 19

1949: 480,000 UMW members go on strike in Pittsburgh.

Cal shared a checkout line with a miner just off work, his face still smudged with coal, his arms full of meat and potatoes and a large glass jar of tomato juice held awkwardly by the tips of his fingers.

“Looks like you could use a basket,” Cal said smiling, picking up a small red plastic basket by the checkout counter. The miner looked unbearably weary.

“It’s okay,” the fellow said, glancing nervously around. Then he looked directly at Cal and tried to smile back. “Don’t much trust the equipment, I guess. My daddy taught me a long time just to trust my own two hands.” He looked over at the checkout counter. “Them scanner things? They work, okay? I mean, they don’t do nothin’ to the food, do they?”

“They just check the price.”

Obviously embarrassed, the man nodded. “I thank you. Guess that sounded dumb. But workin’ in the mines … well, after a while you just quit trustin’ machinery.”

“I heard there’s been some problems over there. Gas? Explosions, right? I’d be finding another line of work right now.”

The miner snorted. “I’m just like my daddy. I don’t know nuthin’ else. I got kids to feed. Doctor at the company clinic says they’re too small. Somethin’ in our house, maybe, he says. I dunno what I can do. Sometimes I lay awake thinkin’ it’s somethin’ I brought up out of that mine, on my hands, on my clothes. Doctor says that’s foolishness. But I’m just like my daddy– can’t sleep, jumpy, don’t know nuthin’ much about anything but the mines, and I went down in those mines the day I turned seventeen. So I musta got it from him, whatever it is. Like I couldn’t stay out of them. Somethin’ he brought up out of that hole with him. On his hands. On his clothes. Now my kids gettin’ it, too.”

There was an explosion. At the mi

ner’s feet, the juice bottle had dropped and burst, spraying bright red tomato juice and glass slivers everywhere. The man’s face was white, eyes fixed, lips quivering, and unresponsive, no matter how much Cal or the store manager shouted

SEPT. 20

1878: Upton Sinclair, author of The Jungle, is born.

1952: The debut of “The Jackie Gleason Show.”

Cal had always had problems answering his kids’ questions about meat.

“Where do the hamburgers and hot dogs come from, Daddy?”

“Cows and pigs, sweetheart.”

A shocked little gasp. “You mean like Elmer? Like Porky Pig?”

“Those aren’t real, honey. Porky Pig isn’t a real pig. He’s just a cartoon character.” Cal had visions of a slavering wolf in a butcher’s apron attacking Porky with an animated chainsaw, cutting him into slices, dealing him out to other wolves as he would a deck of cards.

“Well, he’s real to me.”

“I know he is, honey, I know. But the pigs we eat, they’re not like Porky. Porky is something special. He’s like a dream, I guess. Porky Pig is a dream pig.”

“Why do we eat piggies, Daddy? Even if they aren’t dreams?”

“I don’t know. Life eats life, I guess. That’s what makes it life. Life even eats dreams, sometimes.”

In college Cal had worked for a butcher for a while, along with some of his classmates. Sometimes on the night shift they grew so bored and tired they entered a kind of drunkenness. They’d turn the dressed chicken carcasses, the fish heads, the calf heads, into hand puppets and act out scenes from The Honeymooners.

“One of these days, Alice … to the moon!” And the eyes of the calf head would bulge and leer angrily. The small chicken carcass would back up cartoon-like, cowering, knowing that a bodiless calf’s head with dreams and no abilities was capable of almost anything.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

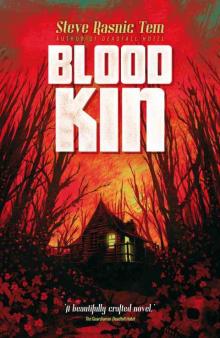

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin