- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

Deadfall Hotel Page 3

Deadfall Hotel Read online

Page 3

He looked around at the empty seat. He twisted his head and shoulders, looking for something else on the backseat with his sleeping daughter. He peered into every corner of the five mirrors, trying to ferret out her pale, languid face, her terribly relaxed smile. But she was nothing, and she was behind. Are you sure? She still insisted. Are you sure?

“Objects in mirror are closer than they appear,” he replied, and said it again. And again. “Objects in mirror are closer than they appear,” until Abby shut up, and let him drive.

According to Jacob’s crude, hand-drawn map, the Deadfall was located somewhere on the edge of a huge lake. But the map did not include any indications of relative altitudes. Richard was bothered by a vaguely anxious, cartoony fantasy of a cliff two miles high, the Deadfall Hotel poised on the edge as if ready to tumble into the dark waters below. He glanced at the map again, half expecting to see ‘Here Be Dragons’ scrawled into the blank area beyond the rectangle labeled ‘Deadfall.’

“We like our privacy,” Jacob had said at one point during the interview. Indeed.

In the rear view mirror, Richard could see Serena reverting a few years, clutching her dolls to her chest. Her thumb strayed vaguely toward her mouth and he smiled and she seemed almost horrified to see him looking back at her.

In the side mirrors, the world behind them turned over onto itself, spreading ripples of distortion all the way out to the horizon. Trees crept up to the sides of the car before tumbling away. The station wagon bent itself to better fit the curves.

The road went to gravel, to dirt, to concrete, to asphalt, seemingly at random, with no apparent relation to the amount of traffic or the degree of civilization. At the top of one hill, the narrow gravel and dirt path became smooth black paving for approximately one hundred yards before reverting to gravel and dirt again. There had been no houses in sight. There had been no other vehicles since three turn-offs before. None of the fields had been plowed, but under one tree lay the rusted husk of an ancient tractor.

They passed through several small communities, the largest being Mad Devon, a grouping of perhaps three dozen structures, including a church and a school. Richard noticed people coming out onto their porches to watch, and on the school playground the handful of children halted their games to stare. A short distance outside Mad Devon, they came to a still narrower paved highway leading off at an angle into a patch of ragged woods.

A huge rock outcropping rose – ‘King’s Head,’ according to the map. That’s exactly what it resembled: a large-nosed, high-cheek-boned head some thirty feet high, topped by a ragged crown of stone finials and spires. It was obviously natural, but its location here seemed unlikely. Richard hesitated only briefly, then took the road into the woods.

After about a mile, the ancient paved road fell apart into gravel. “Do people really come here for vacations, Daddy?” Richard could barely hear her.

“Sure they do, sweetheart. Otherwise they wouldn’t need a hotel manager, now would they?”

As they drove further, he tried to see through the few narrow gaps exposing daylight, and was tantalized by glimpses of distant walls and windows, roof edges and stone corners. It must be huge! he thought. Too huge to be a single structure, in fact. Maybe there was a town by the hotel.

Then suddenly they were passing through the ornate iron gates, traveling the winding driveway that snaked its way between the darkly malformed trees and up the wide slope of lawn spread before the Deadfall Hotel, and Jacob’s voice was in his head, describing the Deadfall as he had that day he’d interviewed Richard.

There was the pile of deadfall, much like the woods but older, deader, even more complicated in their involvement with each other, swallowing up the grove of trees struggling to keep its still living extremities up in daylight. The extent of the dark pile appalled him – it was many times the area of the huge hotel itself, like an enormous sore across the hillside. Richard had a sudden, overwhelming urge to destroy the thing, to burn it and bulldoze the remnants, then to change the hotel’s name to something more inviting. He remembered words like ‘guardian’ and ‘conservator’ from Jacob’s rambling talk, and vaguely understood that those words applied to the grounds as a whole, including this abomination of landscaping.

That chaotic pile of deadfall was made all the more alarming by the civilized feel of the rest of the grounds: hundreds of square yards of well-manicured grass, the occasional ornamental tree, ornate iron lawn chairs and benches, several elaborate flower beds in paisley patterns. The only exception to this appearance of gentility was the great gray hulk of a gazebo, in slow-motion collapse into a cluster of trees and bushes.

The hotel itself was beyond impressive, as Richard had expected, although somewhat confusing in its architecture and spatial balance. Every few feet was an angle that appeared wrong, a window out of place, a chimney at an unlikely slant, exterior wall planes which met with vaguely disturbing results. The freeform rhythm of its lines was discomfiting. He could imagine it in a high wind, its odd geometry forcing a strange music through its spaces.

He stopped the car twenty feet or so away from the entrance. He just wanted a few more seconds to take it all in, before the angle became too sharp for a comprehensive view. He would need to drive a little closer for them to unload. But was that what he wanted to do? Or should he just circle back down the driveway and leave? At the moment, that seemed by far the more prudent course.

His hands gripped and ungripped the steering wheel. Then his right hand strayed toward the gear knob.

A sharp tap on the glass. “Welcome.” Richard twisted around, stared up into Jacob’s narrow face at his driver’s side window. “Didn’t mean to startle you,” the old man said.

For no apparent reason, Richard thought, he’s lying.

Jacob chatted easily with Serena, helping her unload her ‘special things’ from the back seat – an old Teddy Bear, dolls, a copy of Black Beauty, a box of jewelry that had belonged to her mother. Richard fumbled with a few small boxes and cloth bags on the front passenger side floorboard containing some of Abby’s journals, one of her dresses, a few books and knick-knacks most clearly expressive of her personality. Things he could not let go of, and now found he could not leave unguarded in the car.

Jacob and Serena passed him, their arms full of Serena’s things. Jacob eyed him appraisingly. They went in ahead of him, Jacob pushing the enormous front door open easily. A hushing sound escaped, a massive exhalation. Richard had a moment to consider whether there were sophisticated hydraulics at play here, when the door squeezed shut in front of him.

He paused with his arms full, waiting for Jacob to realize he didn’t have a free hand, and open the door for him. But time passed, the boxes – as small as they were – grew heavy in his arms, and Richard grew annoyed. He leaned back to peer at the carved heads poised over the entrance. He looked back at the door, whose paneling appeared as solid, unmovable, and weathered as stone. A growing sickness climbed the walls of his stomach. He’s taken her, he thought, when the door eased quietly open.

“Sorry. That door is supposed to stay open a bit. It must require adjustment.” Jacob’s grayish face floated in the darkness just inside the door. Richard willed his eyes to adjust quickly, but they were stubborn. Not wanting Jacob to see his difficulty, he stepped, unseeing, into the hotel.

A sense of poorly lit ornateness was all that came through as he blinked several times, his eyes tearing. His breath caught in his throat as he feared he might actually weep.

“Here, let me,” Jacob’s voice said, just before Abby’s things were taken from his arms.

“No, wait!” He could see clearly now, Jacob’s back receding toward his left.

“I’ll just put them on the front desk,” Jacob threw back over his shoulder. “Get yourself acclimated before trying to move anything else.”

Serena, a serious look on her face, was examining a huge painting on the wall: a hunting scene, a dozen or so dogs attempting to bring down a great, slave

ring bear. The mounted, cloaked hunters had pale faces expressing shock and awe. She held her old teddy bear dangling by one arm.

He looked around: the entrance was domed, several stories high, studded with interior windows, which he assumed opened onto the upper floors. A huge number of similarly old and dark paintings covered most of the wall area of this space – many hung too high to see in any detail, except perhaps from one of those high, interior windows. The air was hot and dusty. Around the entrance were a number of shadowed recesses, the roots of hallways, and rows of full-length mirrors: carefully placed, it seemed, some of them angled away from the wall so that anyone walking there would be distorted, and their distortions multiplied.

Then he saw there was a wider recess where Jacob now stood, carefully placing Abby’s things on a polished redwood counter.

Richard watched him touch her things and held his breath. It wasn’t as if he was touching her, there was no her anymore. She wasn’t here; he hadn’t brought her here. She wasn’t in those things; she wasn’t anywhere. What people did with the things of the dead was what people did.

He closed his eyes, making himself stop. He opened them again, tried to concentrate on the beautiful counter, the figures carved into the front, the delicate columns on either end up which more figures climbed, to be woven into the design of the bridging valance.

Behind the counter he caught the gleam of mirror, a wall of small partitioned boxes, and more doors in the shadows.

But the most prominent, impossible-to-ignore feature of this grand entrance was the great staircase directly opposite the front door. It spilled down from the second or third floor – difficult to tell which, with the four or five tributary stairs joining it at various points on its height, massing like waves until it flooded most of the area before the door. It pushed the occasional tables and sitting chairs off into the corners by the windows, stealing the bulk of the lobby floor, threatening to ram out the front wall of the hotel. Ridiculously impractical, of course – not content to merely break up the traffic flow through the hotel’s first floor, it stopped it all together – it was still, undeniably, eccentrically, magnificent. Richard imagined it as the corpse of some gigantic mythological creature, slain by forces unknown, left to rot here at the center of the hotel.

“Nice stairs, huh, Daddy?” Serena said softly behind him.

“Oh, yes, sweetheart,” he practically whispered. “Very nice.”

“Enid has made you a meal,” Jacob said. Richard looked around, unable to place his voice. Finally he found him: on the wall past the desk, in a corner almost hidden by the great stairs. He stood in the opening to a narrow hallway, beside a very short woman in a dark dress, her face an oval of olive skin, creased severely once for a mouth, and again for a channel to contain the tiny, moving eyes. Her nose was slight, with no detectable underlying structure.

“Thanks. Hi.” He raised his hand shyly, but she didn’t respond. He moved his hand behind his head as if to stretch.

“It was a long drive. Enid’s son can move the rest of your belongings into your new quarters. This hallway will take you there, and to the staff entrance for the kitchen and dining rooms.” A broad, squarish man slightly taller than Enid, but with almost identical features, stepped from behind the pair and walked swiftly toward the door. He appeared not to spare a glance for either Serena or Richard, but Serena couldn’t keep her eyes off him.

“Where’s the rest of the staff?”

Jacob said nothing for a moment, appearing to consider his words. “Actually, this is all the staff with which you will need to concern yourself.”

“But a hotel this size, there must be maintenance staff, recreational people and, my god, housekeeping? This place must require an army of housekeepers!”

Jacob’s smile was crooked, as if distorted by scar tissue just under the surface. Richard had already determined that this would be the man’s most annoying trait. “I personally will serve as your maintenance crew,” Jacob replied. “We have found in many cases that the previous managers are often the best-trained to undertake such a role, if they are willing. And frankly, there are always discretionary issues involved when you hire, for lack of a better term, ‘outsiders.’ Most of our residents provide their own entertainment, as it were. For the occasions when a bit more is required, you will serve a dual role. I assure you that duty will not be an onerous one.

“As I believe I told you during your interview, we do employ a cleaning crew. But they prefer working late at night, after the majority of our residents have gone to bed. They are quite shy – I doubt if you will encounter any of them during your tenure here. The advantage to that, of course, is that it gives you one less responsibility. Your challenges will be significant enough without troubling yourself over distracted maids and dirty linens.”

Well, Abby, he thought, I can’t even imagine what you’d have to say about all this.

The night of the Carters’ arrival I worked late behind the front desk, arranging the materials I would use to train Richard in his new duties. I had prepared a number of exercises intended to take him through checking guests in, looking up any available data related to their history with our hotel, making notations as to dietary and exercise requirements, and what to do in the case of any glitches that might occur. I studied my diary entries for the early days of my own tenure here, to refresh my memory regarding my initial difficulties with this work. Perhaps I was over-prepared, but despite my long tenure, this was my first opportunity to train new staff. I swore to myself I would not repeat my predecessor’s pedagogical mistakes.

I heard an exaggerated throat clearing and was surprised to see Enid standing there. “Enid. Rather late for you, I should think.”

“Yes sir, it is. I just wanted to point out that you never told me our new manager would be bringing a child into the Deadfall.”

I admit to feeling a certain defensiveness, but I remained professional. “Well, no. I suppose it slipped my mind,” I replied.

“Yes sir, I would just like to also point out that it has been a number of decades since a child was in residence here.”

“True. And isn’t she charming? She veritably brightens the room, don’t you agree?”

“Yes sir, I agree. She is very charming. But do you think we’re prepared sufficiently to keep her safe?”

“You know my position on safety issues in general, Enid. It applies to children as well. Safety is quite important, but I also believe a child is safer here than on the average, say, New York City street.”

“I am aware of your position, sir. I just wanted to make sure you were comfortable with it, when applied in this specific, and not at all theoretical, case. And that was all I had to say.” She left without waiting for my reply. She had annoyed me, but she had made me think.

– from the diary of Jacob Ascher,

proprietor, Deadfall Hotel, 1969-2000

Chapter Two

BLOODWOLF

There have been between thirty and thirty-six managers of the Deadfall Hotel during its existence. The exact number is unknown. Their tenure has ranged from one hour to thirty-one years. I have the honor of having the longest employment at this establishment. The name of the unfortunate individual who had its shortest employ has been lost, or perhaps suppressed, but I refuse to pass judgment on how information is handled regarding such matters. The records I have examined simply refer to a ‘spontaneous combustion event’ shortly after the woman’s arrival.

What that poor woman’s demise (if ‘demise’ it was) illustrates is that there is a certain amount of danger involved when one resides in, and indeed is employed by, such an institution. Several past managers terminated their employment as a consequence of physical disappearance. A few others grew ill with undiagnosable maladies that made their sunset years rather uncomfortable. Whether these incidents were the result of disease contracted from a resident, a disorder native to the materials used to construct the hotel itself, or a condition of a personal nature comple

tely unrelated to their employment, we will never know. But the potential for peril would be foolish to deny.

And yet wherever men or women choose to walk or reside, they will be accompanied by danger. And this danger affects not only themselves, but spouses and children as well. It is a simple fact of life. Before my time, several of the managers had families who shared the life of these grounds with them. And in a few cases, tragedies did occur. But wherever we are, whatever we do, there will be children in danger. We can only try our best to protect them. This hotel, ultimately and on average, is no more dangerous than most of the haunts of men and women. I sincerely believe this. It is also evident, unfortunately, that it is the nature of life that no one, at least no one deserving the classification of human being, survives the endeavor.

None of the therapies used by humans upon humans is without pain. I hesitate to call this position therapy, but I do know that for many of the managers, therapy has been the end result. That has certainly been true in my case. Those individuals chosen for this position – and although the basic interviews are conducted by former managers, the candidates come to us by methods often opaque and without comprehension – tend to be men and women who have experienced terrible trauma in their lives. They come haunted by loss, perhaps some terrible deed perpetrated either by them or upon them, and they carry these traumas around with them like fantastic creatures perched on their shoulders who alter the very way they see the outer world. At the end of their tenure many, but certainly not all, have been better off, in some way.

Recruitment can be difficult. Oftentimes you must balance your belief in complete honesty with the higher needs of the institution that employs you, the clientele who depend on you, and the ultimate needs of the person with whom you have not been completely candid.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

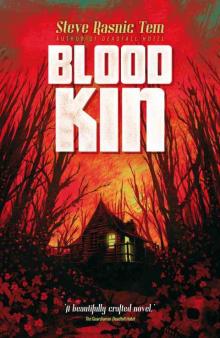

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin