- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

Absent Company Page 4

Absent Company Read online

Page 4

The man had looked frightened, stammered “Ahorita,” right away, then left through a curtain behind his stand. Cliff had become angry, confused, knowing that here Ahorita could mean hours. Ahorita, señor; I’ll bring it. Ahorita, this very afternoon. He heard it all the time.

Cliff slipped away when he saw the herb seller coming back around the corner, a member of the state police in tow, police who consider you guilty until you prove otherwise, especially a drunken, unshaven gringo. Cliff secreted himself within the fast-moving crowd.

Mala gente … mala gente … mala gente …

He felt a little better the fourth day, enough to dress up and treat himself to a small excursion to the Jardin Borda, the Borda Gardens, at Morelos and Hidalgo, the former summer retreat of the Emperor Maximilian and the Empress Carlotta. Fifteen pesos to enter the small preserve of the gardens proper.

Afterwards he had a drink at one of the fanciest restaurants in the city, Las Mananitas, a Spanish colonial house doubling as a hotel and restaurant. Behind the building were tropical gardens stocked with peacocks, toucans, macaws, cranes, and parrots. Here he could sit on the lawn among all the birds and sip a cool drink. Forty-five pesos.

He picked up a prostitute on the way back to his hotel. Twenty-five pesos. It was dark by the time they arrived at the front of the building. She seemed nervous, anxious to get upstairs and away from him.

“Mala gente …” she whispered hoarsely.

“What!” He turned and grabbed her by the wrists. “What do you mean by that?” His voice shook, tears welling up in his eyes.

“The people here, señor,” she wheezed, eyes darting fitfully. “See? How do you say … the criminal element?”

Cliff turned his head slowly, taking in the dark figures on the street corners, grouped in alleys, lounging in front of buildings. He sighed and dropped her hands, “Sorry … I didn’t mean to do that … please, please let’s just go up now.”

He had been halfway between waking and sleeping, drifting. Somewhere out in the snow? No, it had been sand, hot desert. Was he sure which? He half-remembered a dream about his father’s death, the old man lying there, scowling in a stiff headdress as if he were a priest or god, his eyes wild, tongue protruding, and God forgive him, Cliff just didn’t care, it wasn’t in him to care at all. The old man had starved all the caring out of him a long time ago.

“Do you want me to do something?”

His eyes went open immediately.

“You want me to do something …”

Cliff jerked up in bed and shouted when he saw the dark, sharp-featured silhouette bending over him. He pushed it away with frantic fingers, scrambling up on his knees in the bed.

“You did not seem interested! I was just trying to help; I didn’t know what you wanted!” The prostitute shouted at him. Cliff sat quietly, rubbing his eyes like a sleepy child.

She was slipping rapidly into her clothes, muttering in unintelligible Spanish, coughing, when he began to cry.

“I’ve tried … I really have.”

The prostitute stopped and stared defiantly at Cliff as he continued to cry in loud, choked-off sobs. “Malvado!” she spat, then turned on her heel and left through the already open door.

Cliff looked around at the darkness in the room, the dim light from the hall filling his open door, and continued to talk, to chatter. “I tried, I did try.”

The door closed slowly until only a thin crack of light remained.

Cliff collapsed back on to the bed. His eyes, even through his tears, were slowly becoming accustomed to the semi-darkness, the crack of light through his door striping the humped forms of the room’s furniture, the streetlight filtered through the thin shade behind him turning his sheets a dingy, pale yellow.

“It hasn’t been easy for me,” he said as he turned his head side to side as if addressing an entire crowd in his room, “it has never been easy.” And he saw the tall shadow figure at the foot of his bed.

He sobbed, wide-eyed, watching the figure as it moved around the bed, towards his night table, his pillow, “I tried to be a good man,” brushing back its heavy poncho from arms which were long, angular. He choked, as the arms, ended with thin bony fingers were reaching out to his chest, “If I’d just touched,” he said softly, as the hard, steely, icy fingers touched him, that touch spreading throughout his body, freezing the brain, icing over the skin, spiking the heart. And, for the moment, stopping everything.

“Cold …” the shadow whispered.

He could not move, just stare into the face of the stranger, whose profile now, indeed, was his, but changed so quickly, even before the recognition had quite registered, and then the stranger’s face was blank again, devoid of meaning, expressionless.

But behind the stranger another shadow moved, came around beside the figure, a small head beside the stranger’s broad shoulders. Then the small shadow crept into the dim light from the door, and Cliff saw that it was his own son, the face striped across one eye and the nose by the crack of light, the other eye impassive, the lips smooth, together, untroubled. A beautiful child’s face.

As the heavy weight of cold crept through his body, every pore, every extremity filling with the mass of ice, Cliff thought of his own face, and which expression he could choose, with these last few seconds, to make permanent.

Leaks

“A family’s got to do things together, each and every day,” Owen’s father always said. “And do things best as you can, like you mean them. That’s what makes right living. Those little things you do every day. Like working in the garden, or working on the house, even going to a ball game together. You do them regular and it’s just like praying. Even if you got nothing else but that, everything’ll turn out okay.”

His father’s rituals. Owen used to think they’d drive him crazy. Maybe they had. Maybe he should have asked his wife if they had—Marie would know. But he hadn’t even talked to her on the phone since she’d left him two years ago. He had no idea where she was. She hadn’t even tried to contact their older son Wes, and that surprised him. Her leaving in the first place had surprised him. As had her taking Jimmy, the younger, and leaving ten-year-old Wes alone in the house that day. Owen couldn’t imagine what she’d been thinking.

He hadn’t really known Marie at all. And now, he had to admit, he knew his sons even less. His family must have been slipping through his fingers for years and he hadn’t noticed a thing.

“I hate it here.” That was Owen’s mother. But it might have been Wes. He’d said that when they weren’t more than three feet inside the doorway of the old house. Owen had felt like hitting him. “I hate it here,” she always said. The regular, ritualistic complaints, day after day. “Everything’s so damp. I can’t leave any of my clothes in the trunks for fear they’ll mildew on me. And it’s so plain. It’s like living in a box!” Then she’d drag Owen to her closet door and make him look in. The mildew spread over the old floorboards like pale green paint. It nauseated him. He’d look back over his shoulder at his father, who watched them from just outside the door but never came in. It embarrassed Owen, the way she’d show him things wrong with the house as if his father wasn’t standing right there.

“It’s a great deal, hon.” That was Owen’s father. “County used to use it for storage, I think. Marine equipment, or something. That’s why it’s plain. But hell, doesn’t have to be that way forever. We’ll fix ’er up. Besides, it’s the only way we’re going to get a house right now.”

“But it’s so wet here. Makes my skin crawl. Like I’m always tasting bad water.”

“It’s close to the water, don’t you know,” he said, and laughed each time. Each time Owen’s mother trembled, and after a few years in that house Owen understood why.

The voices were so clear, only slightly muted as he recalled them. As if they’d leaked from the walls that had stored them these many years.

His father’s attempts to placate his mother were useless. Owen didn’t think he’d really

tried. Most of the time he ignored her complaints, as if he had other things on his mind and counted on the rituals to make things right in the family.

“Almost sunset. Let’s get those chairs ready and head down to the creek bank.” He never said it loudly, but the firmness of his expectation was clear. It was something the family did every night, even in the coldest weather. “Owen, you shut the door behind your mother.” Always the same instruction.

The family trooped the hundred feet to the creek bank, a hundred muddy feet most of the time, the brownish-yellowish grass lying flat over the wet loam like a badly done toupee, Owen’s father always in the lead. “In case of water snakes,” he said, and winked at Owen’s mother. A little cruelly, Owen always thought. One evening she’d been terrified to distraction by one of the enormous earthworms that were always lying around, forced out of their holes by all the water that saturated the ground near the creek. Owen had to admit it was the biggest earthworm he’d ever seen. Freakishly big.

They each carried a lawn chair. “Okay, now you sit there, Mother. And you there, Owen.” His father stared at them as they struggled to unfold the stiff old chairs. It always made Owen terribly self-conscious. And then inevitably his father would grab the chairs out of their hands and show them how to grip the aluminum tubing, how to snap the chair out just so. “Why can’t you people ever learn the proper way to unfold a lawn chair?” Then they’d all sit facing the creek. “Good to do things together,” his father would say several times during the next hour. “Family needs its routine.” And that would begin the lecture for the evening.

They’d sit there, watching the sunset redden the greasy water below them, dark water that seemed too thick somehow, too substantial, that lapped at their feet so hungrily.

“Beautiful evening,” his father would say. “And look at how pretty the water is!” Owen could taste the creek—the air was full of it. It was like drowning.

That was a long time ago. Now he and Wes were back.

The first day back in the house Owen wandered aimlessly from room to room. Wes stayed in the back yard and complained. Sometimes Owen would catch a glimpse of him through a yellowed window pane. At thirteen he was tall and lanky, a dishwater blond much like Owen himself, much like Owen’s father. Owen felt a sudden pride in his son at that moment, but he doubted he ever would tell him. Something made it too hard.

Several times Owen had to stop Wes from throwing rocks at the house. He was rapidly losing his patience; he was sure if Wes didn’t stop he’d take a backhand to the boy. He couldn’t understand why his son would do that; he couldn’t understand why he was so angry all the time. He’d talked to him, when he could, about Marie’s abandoning the two of them, and Wes really seemed okay about all that.

But Owen knew he was overstating things—Wes certainly wasn’t angry all the time. He just had a talent for picking the wrong times to be unruly.

Once during that first afternoon in the house Wes brought Owen flowers. “For the lady of the house,” he said with a grin.

Owen was touched. “Lady?”

“Sure. You’ve been hanging closer to home than an old maid, Dad.”

Owen sighed. “I am being a little silly I guess.” He laughed when Wes nodded in an exaggerated, comic fashion. Owen smelled the flowers. “Terrific. Where’d you find these?”

“Out by the back gate, near the woods. They’re all over the place out there.

“Yeah. Seems like I remember my father having a bed of perennials out there.” He looked up. “I’m sorry, Wes. How are you doing?”

Wes let loose a lopsided grin. “Hey, no sweat. I just feel a little strange out here is all. What can I do for you?”

“You’re already doing it, Wes. You’re already doing it.”

He left his own and Wes’s meagre pile of belongings in the front hallway, right where they dropped them. He travelled light, never thinking of any particular place as home, determined not to let his own possessions tie him down.

Very little had changed in the house in fifteen years. In his mother’s sewing-room a swatch of bright blue cloth was still wedged under the needle. The dust had only now begun to accumulate; his father had been dead a week, the house untended for two.

He knew the house would dirty quickly. There seemed no end to the work required to maintain a house. Owen found himself listening to the walls.

“It doesn’t stop! I’ve cleaned the floor twice today already!” His mother was on her hands and knees, her back hunched, scrubbing at the kitchen tiles. No matter how much she scrubbed the seams still looked muddy. Her face was red. Her hands raw, nearly bleeding. She was sobbing.

In his father’s den a newspaper from last month was neatly folded on his overstuffed chair, the same soft brown chair Owen remembered. The house had been a lifetime of work. His father’s lifetime.

His father had seen Wes only once or twice; he’d never seen Jimmy at all. “Can’t come out there now, Owen. The house needs too much work right now.” The same excuse, again and again. “No time for visiting with all this work to be done.”

“I can’t do this anymore!” His mother said it almost daily, ritualistically, her hand clutching a filth-encrusted rag, her eyes red from the dust and crying. The mold came back no matter how thoroughly she scraped it away. The tiles peeled from the floor. The window sills warped. The paint flaked away. “This house! This house!” She complained all day when his father wasn’t home, complained just to Owen, and to those always damp, clammy walls. His father made her sound crazy.

“It’s that fancy house your mother’s folks own.” His father spoke to him as if his mother wasn’t standing right there, slamming pans around as she fixed dinner. “It’s got her spoiled, I think. Your mother doesn’t seem to know about working to make something good. Like this house. It’ll be a showplace someday. If we all aren’t afraid of a little work.”

A lifetime of work. Owen knew he should have sold the house, or denied the will, anything other than, in fact, to take possession of it. But his father had worked so hard. His father had told him again and again that children owed their parents, and Owen believed that. His father had manipulated him as skilfully and persistently as he had manipulated the rules by which houses fall into disrepair.

All the furniture and appliances looked new in that house. It was only by looking very closely that Owen could see the countless, minute indications of repair—the re-weavings, the welds, the glue repairs, the parts replaced by parts of ever-so-slightly different color. Such fine repair work. So much effort spent to gain such small results.

He could smell the dampness in the house.

It was only after dark that Owen realized he and Wes really didn’t have to stay in the house. Wes had known, had insisted, they didn’t have to stay, but Owen had other voices to listen to.

“We can leave all our stuff here, Dad. None of it really matters that much; isn’t that what you’re always saying?” Owen gazed at his son in surprise. Wes was almost in tears. Owen wondered how the boy could even know.

A battered suitcase and a few boxes of clothes and paperbacks. Owen could hire an agent to handle the sale of his father’s house.

He gazed at the new woodwork around the doors and windows, the new paint that had replaced the old, the carefully wrought repairs in the furniture. It was insane, the amount of wasted labor, wasted life that had gone into keeping this house alive.

When next he looked out the window it was dark. Wes had fallen asleep on the couch. He could hear the creek lapping at the muddy bank only a short distance away. A damp sensation crept into his throat. Suddenly Owen was afraid to step out on to the soft, fog-shrouded ground that surrounded his father’s showplace. Wes was asleep; it was best to spend the night. Owen covered him with a blanket—it had always been easy to catch colds in this house.

Owen left their things in the hallway and slept upstairs that night. First he tried his old bedroom, but after gazing at all its carefully repaired toys he discovered he c

ould not sleep there. He used his father’s old bedroom.

His mother left the house, and the creek, when Owen was thirteen. He never saw her again. He knew it was that nightly ritual that finally did it, for his mother had always hated that creek. She said she’d never seen water like that anywhere.

Owen woke up on his second day in the house with an enormous headache, his chest sore and his body riddled with aches and pains. Opening his eyes seemed unusually difficult, as if the wet headache were pushing his eyelids down.

The wooden floorboards creaked—too loudly—as he padded his way towards the bathroom. He stopped at the bathroom door and looked down. He felt dizzy. The floor looked warped, buckled towards its center. He grew nauseous and fled into the bathroom.

He hovered over the sink, barely able to control his sickness, his arm supporting him against the wall. The wall tiles felt slick, slimy beneath his palm. He wanted to remove it from the tile, but he hadn’t regained his balance yet. He stared down at the faucet. Water was flowing in a silver line into the drain, noiselessly, with almost no splash, like an unbroken tube. He suddenly couldn’t bear the thought of touching it, of breaking its symmetry.

He dressed quickly and went downstairs. Wes’s bags were gone. He started to call him when he heard the footsteps overhead, in his old room. He couldn’t suppress a smile as he walked past his stuff and opened the front door.

With his first steps outside he noted how quiet it was. You couldn’t even hear the creek.

He walked around to the patio facing the garden. The cement slab was cracked—you could see the traces of patching material. It had cracked every spring when the water pushed the ground up under it, and his father had repaired it every spring with the same patching compound, which made the slab good until the next spring. Owen looked out on the garden; it was badly in need of weeding. Several potted plants left out on the gravel pathways had tilted where the gravel had sunk beneath them. The little garden house his father had built when Owen was thirteen had lost some roof tiles. They protruded from the barren garden like praying hands. The bright yellow paint on the back fence had paled and was peeling away from the damp wood. The woods drooped over the fence, leaves dripping steadily.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

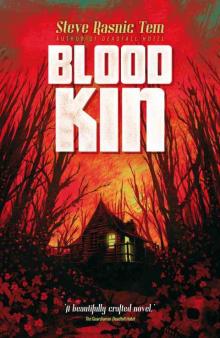

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin