- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

The Man on the Ceiling Page 4

The Man on the Ceiling Read online

Page 4

I am wide awake now, holding my sleeping little boy in my lap and rocking, rocking. Shadows move on the ceiling. The man on the ceiling is there. He’s always there. And I understand, in a way I don’t fully understand and will have lost most of by morning, that he gave me this moment, too.

I was never afraid of dying, before. But that changed after the man on the ceiling came down. Now I see his shadow imprinted in my skin, like a brand, and I think about dying. I think about leaving my children without a father.

That doesn’t mean I’m unhappy, or that the shadow cast by the man on the ceiling is a shadow of depression. I can’t stand people without a sense of humor, nor can I tolerate this sort of morbid fascination with the ways and colorings of death that shows itself even among people who say they enjoy my work. I never believed horror fiction was simply about morbid fascinations. I find that attitude stupid and dull.

The man on the ceiling gives my life an edge. He makes me uneasy; he makes me grieve. And yet he also fills me with awe for what is possible. He shames me with his glimpses into the darkness of human cruelty, and he shocks me when I see bits of my own face in his. He encourages a reverence when I contemplate the inevitability of my own death. And he shakes me with anger, pity, and fear.

The man on the ceiling makes it mean that much more when my daughter’s fever breaks, when my son smiles sleepily up at me in the morning and sticks out his tongue.

So I wasn’t surprised when one night, late, two a.m. or so, after I’d stayed up reading, I began to feel a change in the air of the house, as if something were being added, or something taken away.

Cinnabar uncurled and lifted her head, her snout wrinkling as if to test the air. Then her head turned slowly atop her body, and her yellow eyes became silver as she made a long, motionless stare into the darkness beyond our bedroom door. Poised. Transfixed.

I glanced down at Melanie sleeping beside me. I could see Cinnabar’s claws piercing the sheet and yet Melanie did not wake up. I leaned over her then to see if I could convince myself she was breathing. Melanie breathes so shallowly during sleep that half the time I can’t tell she’s breathing at all. So it isn’t unusual to find me poised over her like this during the middle of the night, like some anxious and aging gargoyle, waiting to see the rise and fall of the covers to let me know she is still alive. I don’t know if this is normal behavior or not—I’ve never really discussed it with anyone before. But no matter how often I watch my wife like this, and wait, no matter how often I see that yes, she is breathing, I still find myself considering what I would do, how I would feel, if that miraculous breathing did stop. Every time I worry myself with an imagined routine of failed attempts to revive her, to put the breathing back in, of frantic late night calls to anyone who might listen, begging them to tell me what I should do to put the breathing back in. It would be my fault, of course, because I had been watching. I should have watched her more carefully. I should have known exactly what to do.

During these ruminations I become intensely aware of how ephemeral we are. Sometimes I think we’re all little more than a ghost of a memory, our flesh a poor joke.

I also become painfully aware of how, even for me when I’m acting the part of the writer, the right words to express just how much I love Melanie are so hard to come by.

At that point, the man on the ceiling stuck his head through our bedroom door and looked right at me. He turned, looking at Melanie’s near-motionless form—and I saw how thin he was, like a silhouette cut from black construction paper. Then he pulled his head back into the darkness and disappeared.

I eased out of bed, trying not to awaken Melanie. Cinnabar raised her back and took a swipe at me. I moved toward the doorway, taking one last look back at the bed. Cinnabar stared at me as if she couldn’t believe I was actually doing this, as though I were crazy.

For I intended to follow the man on the ceiling and find out where he was going. I couldn’t take him lightly. I already knew some of what he was capable of. So I followed him that night, as I have followed him every night since, in and out of shadow, through dreams and memories of dreams, down the back steps and up into the attic, past the fitful or peaceful sleep of my children, through daily encounters with death, forgiveness, and love.

Usually he is this shadow I’ve described, a silhouette clipped out of the dark, a shadow of a shadow. But these are merely the aspects I’m normally willing to face. Sometimes as he glides from darkness into light and into darkness again, as he steps and drifts through the night rooms and corridors of our house, I glimpse his figure from other angles: a mouth suddenly fleshed out and full of teeth, eyes like the devil’s eyes like my own father’s eyes, a hairy fist with coarse fingers, a jawbone with my own beard attached.

And sometimes his changes are more elaborate: he sprouts needle teeth, razor fingers, or a mouth like a swirling metal funnel.

The man on the ceiling casts shadows of flesh, and sometimes the shadows take on a life of their own.

Many years later, the snake returned. I was very awake. Steve wasn’t home.

I’d been offered painkillers and tranquilizers to produce the undead state which often passes for grieving but is not. I refused them. I wanted to be awake. The coils of the snake dropped from the ceiling and rose from the floor—oozing, slithering, until I was entirely encased. The skin molted and molted again into my own skin. The flesh was supple around my own flesh. The color of the world from inside the coils of the snake was a growing, soothing green.

“Safe,” hissed the snake all around me. “You are safe.”

Everything we’re telling you here is true.

Each night as Melanie sleeps, I follow the man on the ceiling into the various rooms of my children and watch him as he stands over them, touches them, kisses their cheeks with his black ribbon tongue. I imagine what he must be doing to them, what transformations he might be orchestrating in their dreams.

I imagine him creeping up to my youngest daughter’s bed, reaching out his narrow black fingers and like a razor they enter her skull so he can change things there, move things around, plant ideas that might sprout—deadly or healing—in years to come. She is seven years old, and an artist. Already her pictures are thoughtful and detailed and she’s not afraid of taking risks: cats shaped like hearts, people with feathers for hair, roses made entirely of concentric arcs. Does the man on the ceiling have anything to do with this?

I imagine him crawling into bed with my youngest son, whispering things into my son’s ear, and suddenly my son’s sweet character has changed forever.

I imagine him climbing the attic stairs and passing through the door to my teenage daughter’s bedroom without making a sound, slipping over her sleeping form so gradually it’s as if a car’s headlights had passed and the shadows in the room had shifted and now the man from the ceiling is kissing my daughter and infecting her with a yearning she’ll never be rid of.

I imagine him flying out of the house altogether, leaving behind a shadow of his shadow who is no less dangerous than he is, flying away from our house to find our troubled oldest son, filling his head with thoughts he won’t be able to control, filling his brain with hallucinations he won’t have to induce, imprisoning him forever where he is now imprisoned.

Every night since that first night the man on the ceiling climbed down, I have followed him all evening like this: in my dreams, or sitting up in bed, or resting in a chair, or poised in front of a computer screen typing obsessively, waiting for him to reveal himself through my words.

Our teenage daughter has night terrors. I suspect she always has. When she came to us a tiny and terrified seven-year-old, I think the terrors were everywhere, day and night. When I was a girl I had the usual child’s nightmares, but nothing like that.

Now she’s sixteen, and she’s still afraid of many things. Her strength, her wisdom beyond her years, is in going toward what frightens her. I watch her do that, and I am amazed. She worries, for instance, about serial killers,

and so she’s read and re-read everything she could find about Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer, John Wayne Gacy. She’s afraid of death, partly because it’s seductive, and so she wants to be a mortician or a forensic photographer—get inside death, see what makes a dead body dead, record the evidence. Go as close to the fear as you can. Go as close to the monster. Know it. Claim it. Name it. Take it in.

She’s afraid of love, and so she falls in love often and deeply.

Her night terrors now most often take the form of a faceless lady in white who stands by her bed with a knife and intends to kill her, tries to steal her breath the way they used to say cats would do if you let them near the crib. The lady doesn’t disappear even when our daughter wakes herself up, sits up in bed and turns on the light.

Our daughter wanted something alive to sleep with. The cats betrayed her, wouldn’t be confined to her room. So we got her a dog. Ezra was abandoned, too, or lost and never found, and he’s far more worried than she is, which I don’t think she thought possible. He sleeps with her. He sleeps under her covers. He would sleep on her pillow, covering her face, if she’d let him, and she would let him if she could breathe. She says the lady hasn’t come once since Ezra has been here.

I don’t know if Ezra will keep the night terrors away forever. But, if she trusts him, he’ll let her know whether the lady is real. That’s no small gift.

Our daughter is afraid of many things, and saddened by many things. She accepts pain better than most people, takes in pain. I think that now her challenge, her adventure, is to learn to accept happiness. That’s scary.

So maybe the lady at the end of her bed doesn’t intend to kill her after all. Maybe she intends to teach her how to take in happiness.

Which is, I guess, a kind of death.

I know that the lady beside my daughter’s bed is real, but this is not something I have yet chosen to share with my daughter. I saw this lady in my own night terrors when I was a boy, just as I saw the devil in my bedroom one night in the form of a giant goat, six feet tall at the shoulder. I sat up in my bed and watched as the goat’s body disappeared slowly, one layer of hair and skin at a time, leaving giant, bloodshot, humanoid eyes, the eyes of the devil, suspended in mid-air where they remained for several minutes while I gasped for a scream that would not come.

I had night terrors for years until I began experimenting with dream control and learned to extend myself directly into a dream where I could rearrange its pieces and have things happen the way I wanted them to happen. Sometimes when I write now it’s as if I’m in the midst of this extended night terror and I’m frantically using powers of the imagination I’m not even sure belong to me to arrange the pieces and make everything turn out the way it should, or at least the way I think it was meant to be.

If the man on the ceiling were just another night terror, I should have the necessary tools to stop him in his tracks, or at least to divert him. But I’ve followed the man on the ceiling night after night. I’ve seen what he does to my wife and children. And he’s already carried one of our children away.

Remember what I said in the beginning. Everything we’re telling you here is true.

I follow the man on the ceiling around the attic of our house, my flashlight burning off pieces of his body, which grow back as soon as he moves beyond the beam. I chase him down three flights of stairs into our basement where he hides in the laundry. My hands turn into frantic paddles that scatter the clothes and I’m already thinking about how I’m going to explain the mess to Melanie in the morning when he slips like a pool of oil under my feet and out to other corners of the basement where my children keep their toys. I imagine the edge of his cheek in an oversized doll, his amazingly sharp fingers under the hoods of my son’s Matchbox cars.

But the man on the ceiling is a story and I know something about stories. One day I will figure out just what this man on the ceiling is “about.” He’s a character in the dream of our lives and he can be changed or killed.

It always makes me cranky to be asked what a story is “about,” or who my characters “are.” If I could tell you, I wouldn’t have to write them.

I don’t much like it, either, when Steve is asked how he could possibly write from a female point of view. (Notably, I’ve never been asked how I can write from a male point of view.)

Often I write about people I don’t understand, ways of being in the world that baffle me. I want to know how people make sense of things, what they say to themselves, how they live. How they name themselves to themselves.

Because life is hard. Even when it’s wonderful, even when it’s beautiful—which it is a lot of the time—it’s hard. Sometimes I don’t know how any of us makes it through the day. Or the night.

The world has in it: Children hurt or killed by their parents, who would say they do it out of love. Children whose beloved fathers, uncles, brothers, cousins, mothers love them, too, fall in love with them, say anything we do to each other’s bodies is okay because we love each other, but don’t tell anybody because then I’ll go to jail and then I won’t love you anymore.

Perverted love.

The world also has in it: Children whose only chance to grow up is in prison, because they’re afraid to trust love on the outside. Children who die, no matter how much you love them.

Impotent love.

And the world also has in it: Werewolves, whose unclaimed rage transforms them into something not human but also not inhuman (modern psychiatry sometimes finds the bestial “alter” in the multiple personality). Vampires, whose unbridled need to experience leads them to suck other people dry and are still not satisfied. Zombies, the chronically insulated, people who will not feel anything because they will not feel pain. Ghosts.

I write in order to understand these things. I write dark fantasy because it helps me see how to live in a world with monsters.

But one day last week, transferring at a crowded and cold downtown bus stop, late as usual, I was searching irritably in my purse for my bus pass, which was not there, and then for no reason and certainly without conscious intent my gaze abruptly lifted and followed the upswept lines of the pearly glass building across the street, up, up, into the Colorado-blue sky, and it was beautiful.

It was transcendently beautiful. An epiphany. A momentary breakthrough into the dimension of the divine.

That’s why I write, too. To stay available for breakthroughs into the dimension of the divine. Which happen in this world all the time.

I think I always write about love.

I married Melanie because she uses words like “divine” and “transcendent” in everyday conversation. I love that about her. It scares me, and it embarrasses me sometimes, but still I love that about her. I was a secretive and frightened male, perhaps like most males, when I met her. And now sometimes even I will use a word like “transcendent.” I’m still working on “divine.”

And sometimes I write about love. Certainly I love all my characters, miserable lot though they may be. (Another writer once asked me why I wrote about “nebbishes.” I told him I wanted to write about “the common man.”) Sometimes I even love the man on the ceiling, as much as I hate him, because of all the things he enables me to see. Each evening, carrying my flashlight, I follow him through all the dark rooms of my life. He doesn’t need a light because he has learned these rooms so well and because he carries his own light. If you’ll look at him carefully you’ll notice that his grin glows in the darkness. I follow him because I need to understand him. I follow him because he always has something new to show me.

One night I followed him into a far corner of our attic. Apparently that was where he slept when he wasn’t clinging to our ceiling or prowling our children’s rooms. He had made himself a nest out of old photos chewed up and their emulsions spat out into a paste to hold together bits of outgrown clothing and the gutted stuffing of our children’s discarded dolls and teddy bears. He lay curled up, his great dark sides heaving.

I flashed the light on

him. And then I saw his wings

They were patchwork affairs, the separate sections molded out of burnt newspaper, ancient lingerie, metal road signs, and fish nets, stitched together with shoelaces and Bubble Yum, glued and veined with tears, soot, and ash. The man on the ceiling turned his obsidian head and blew me a kiss of smoke.

I stood perfectly still with the light in my hand growing dimmer as he drained away its brightness. So the man on the ceiling was in fact an angel, a messenger between our worldly selves and—yes, I’ll say it—the divine. And it bothered me that I hadn’t recognized his angelic nature before. I should have known, because aren’t ghosts nothing more than angels with wings of memory, and vampires angels with wings of blood?

Everything we’re trying to tell you here is true.

And there are all kinds of truths to tell. There’s the true story about how the man, the angel, on the ceiling killed my mother, and what I did with her body. There’s the story about how my teenage daughter fell in love with the man on the ceiling and ran away with him and we didn’t see her for weeks. There’s the story about how I tried to become the man on the ceiling in order to understand him and ended up terrorizing my own children.

There are so many true stories to tell. So many possibilities.

There are so many stories to tell. I could tell this story about myself, or someone masquerading as myself:

Penguins

Melanie smiled at the toddler standing up backward in the seat in front of her. He wasn’t holding onto anything, and his mouth rested dangerously on the metal bar across the back of the seat. His mother couldn’t have been much more than seventeen, from what Melanie could see of her pug-nosed, rouged and sparkly-eye-shadowed, elaborately poufed profile. Melanie was hoping it was his big sister until she heard him call her, “Mama.”

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

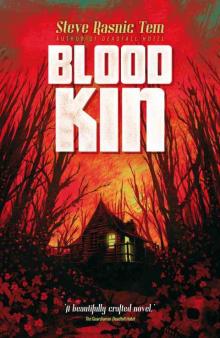

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin