- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

Celestial Inventories Page 6

Celestial Inventories Read online

Page 6

“Human beings?” Elaine laughed. “You know, I always thought you two were wizards, superheroes, magical beings, something like that. Not like anybody else’s parents. Not like anybody else at all. All of us kids did.”

My wife closed her eyes and sighed. “I think we did, too.”

Over the next few weeks we had the rest of our children over to reveal something of our intentions, although I’m quite sure a number of unintentions were exposed as well. They brought along numerous grandchildren, some who had so transformed since their last visits it was as if a brand new person had entered the room, fresh creatures whose habits and behaviors we had yet to learn about. The older children stood around awkwardly, as if they were reluctant guests at some high school dance, snickering at the old folks’ sense of décor, and sense of what was important, but every now and then you would see them touch something on the wall and gasp, or read a letter pasted there and stand transfixed.

The younger grandchildren were content to straddle our laps, constructing tiny bird’s nests in my wife’s grey hair, warrens for invisible rabbits in the multidimensional tangles of my beard. They seemed completely oblivious to their parents’ discomfort with the conversation.

“So where will you go?” asked oldest son Jack, whom we’d named after the fairy tale, although we’d never told him so.

“We’re still looking at places,” his mother said. “Our needs will be pretty simple. As simple as you could imagine, really.”

I looked out at the crowd of them. Did we really have all these children? When had it happened? I suspected a few strangers had sneaked in.

“Won’t you need some help with the moving, and afterwards?” Wilhelmina asked.

“Help should always be appreciated, remember that children,” I said. A few of them laughed, which was the response I had wanted. But then very few of our children have understood my sense of humour.

“What your father meant to say was that moving help won’t be necessary,” my wife said, interrupting. “As we said, we’re taking very little with us, so please grab anything you’d care to have. As for us, we think a simple life will be a nice change.”

Annie, always our politest child, raised her hand.

“Annie, honey, you’re thirty years old. You don’t need to raise your hand anymore,” I told her.

“So what are you really telling us? Are we going to see you again?”

“Well, of course you are,” I said. “Maybe not as often, or precisely when you want to, but you will see us. We’ll still be around, and just as before, just as now, you’ll always be our children.”

*

We didn’t set a day, because rarely do you know when the right day will come along. We’d been looking for little signs for years, it seemed, but you never really know what little signs to look for.

Then one day I was awakened early, sat up straight with eyes wide open, which I almost never do, looking around, listening intently for whatever might have awakened me.

The first thing I noticed was the oddness of the light in the room. It had a vaguely autumnal feel even though it was the end of winter, which wasn’t as surprising as it might normally have been, what with the unusually warm temperatures we’d been having for this time of year.

The second thing was the smell: orangeish or lemonish, but gone a little too far, like when the rot begins to set in.

The third thing was the absence of my wife from our bed. Even though she always woke up before me, she always stayed in bed in order to ease my own transition from my always complicated dreams to standing up, attempting to move around.

I dressed quickly and found her downstairs in the dining room. “Look,” she said. And I did.

Every bit of our lives along the walls, hanging from the ceiling, spilt out onto the floors, had turned the exact same golden sepia shade, as if it had all been sprayed with some kind of preservative. “Look,” she repeated. “You can see it all beginning to wrinkle.”

I’d actually thought that effect to be some distortion in my vision, for I had noticed it, too.

“You know what you want to take?” she asked.

“It’s all been ready for months,” I said. “I’ll be at the door in less than a minute.”

I ran up the stairs, hearing the rapidly drying wooden steps crack and pop beneath my shoes. When I jerked open the closet door it seemed as if I was opening the door to the outside, on a crisp Fall day, Mr. Hopkins down the street is burning his leaves, and you can smell apples cooking from some anonymous kitchen. I brushed the fallen leaves from the small canvas bag I had filled with a notebook, a pencil, some crackers (which are the best food for any occasion), and extra socks. I looked up at the clothes rod, the rusted metal, and nothing left hanging there but a tangle of brittle vines and the old baseball jacket I wore in high school. It hardly fit, but I pulled it on anyway, picked up the bag, and ran.

She stood by the front door smiling, wrapped in an old knit sweater coat with multicoloured squares on a chocolate-coloured background. “My mother knitted it for me in high school. It was all I could find intact, but I’ve always wanted to wear it again.”

“Something to drink?” I asked.

“Two bottles of water. Did you get what you needed?”

“Everything I need,” I replied. And we left that house where we’d lived almost forty years, raised children and more or less kept our peace, for the final time. Out on the street we felt the wind coming up, and turned back around.

What began as a few scattered bits leaving the roof, caught by the wind and drifting over the neighbour’s trees, gathered into a tide that reduced the roof to nothing, leaving the chimney exposed, until the chimney fell into itself, leaving a chimney-shaped hole in the sky. We held onto each other, then, as the walls appeared to detach themselves at the corners, flap like birds in pain, then twist and flutter, shaking, as the dry house chaff scattered, making a cloud so thick we couldn’t really see what was going on inside it, including what was happening to all our possessions, and then the cloud thinned, and the tiny bits drifted down, disappearing into the shrubbery which once hugged the sides of our home, and now hugged nothing.

We held hands for miles and for some parts of days thereafter, until our arthritic hands cramped, and we couldn’t hold on any more no matter how hard we tried. We drank the water and ate the crackers and I wrote nothing down, and after weeks of writing nothing I simply tore the sheets out of the notebook one by one and started pressing them against ground, and stone, the rough bark on trees, the back of a dog’s head, the unanchored sky one rainy afternoon. Some of that caused a mark to be made, much did not, but to me that was a satisfactory record of where we had been, and who we had been.

Eventually, our fingers no longer touched, and we lost the eyes we’d used to gaze at one another, and the tongues for telling each other, and the lips for tasting each other.

But we are not nothing. She is that faint smell in the air, that nonsensical whisper. I am the dust that settles into your clothes, that keeps your footprints as you wander across the world.

THE

WOODCARVER’S

SON

The knock was soft, but the fine wood Alejandro’s father had selected for their front door carried it well, so that the sound still had a fullness when it reached the back of the house where Alejandro had laid down to rest, like the sound a wooden bell might make, or like the now-and-again beating sound of the wooden heart of the house itself.

He padded the long way through the house, avoiding the room where his father wept. All day his father slept, or his father wept, but he would not speak. Not to Alejandro. Not to anyone.

The man at the front door was Señor Echevarría. He had a face of split timber. “Is there work today?” he asked.

Alejandro shook his head sadly. “I am sorry. Not today. My father … my father says not any day. But perhaps someday. But not today.”

Señor Echevarría nodded but did not leave. Alejandro was ashamed,

thinking that Señor Echevarría must recognize his lie. Alejandro did not know why he lied, except that his father’s crying and sleeping embarrassed him. Sleep eased his father’s pain but did not cure it, even after all these months. And as the only one his age in the village, Alejandro felt neither hombre nor chico. He had no one to tell the truth to. He was alone.

“De verdad,” Señor Echevarría said. “After my brother’s wife died, he could not live, and yet he could not die.” He rested his hand against the smooth wood of the door, his thumb caressing the grain one could see but not feel, the grain of a dream. Alejandro did not believe Señor Echevarría could have taken his hand away from the door and walked away then, even if he had wanted to, even if he had been paid. “The village …” His brown eyes drifted to the side, to the narrow dirt road. “They all need the work. But they all still wish him better.”

Alejandro stared up at the man, trying to remember how long he had worked for his father in the woodcarving business, and knew it had been longer than Alejandro had been alive. His mother had told him. His mother had known Señor Echevarría when all who were now old in the village had been young. “But it will happen someday they will not wish him better, they will not wish him well,” Alejandro said.

Señor Echevarría nodded solemnly. “The old ones will tell you that even a fly may have a temper. And the fish that sleeps is soon carried away by the current.” Then the man closed his eyes and leaned forward and kissed the beautiful wood of the door, the most beautiful thing his father had ever carved (“for it is the door to our hearts”) and then he left. And then Alejandro closed this beautiful door and it was all dark inside once again.

*

Since Alejandro’s mother died his father had carved no wood. Sometimes Alejandro would see him in his bedroom walking around, making strange motions with his hands, twisting his face into strange faces, and other idiotic things which might be substitutes for dreaming, and for carving. Perhaps being a fool eased his pain.

But it still angered Alejandro that his father had not spoken to him since the day of his mother’s death. And it shamed him that he had not spoken to his father because he did not know what to say.

“It will be dry again today,” Alejandro said to the wood of the house: the beams, the mantel, the smooth trim, the tightly-knitted flooring. “It has not rained for months. Your beautiful fathers and mothers in the forest must be parched and dying, leaning one against the other with bare, brittle limbs.”

But the wooden heart of the house did not reply to Alejandro, no matter how sweetly he talked. Perhaps it was aware how the boy had stopped oiling its wooden extremities, because they could not afford the oil. Perhaps it knew that it too would die like its relatives in the forest, die from the outside in, the dryness creeping from roof and timber to door to mantel and trim, drying into the heart where it would flake and disintegrate and disperse its memories of the lives it had sheltered up and down the dusty street.

Perhaps it was aware of how little the boy knew of the world beyond this dying village. For Alejandro, the son of the greatest woodcarver in the village, had never seen the forest.

In any case Alejandro decided the house need not worry about the drought, for in the other bedroom his father wept, and the house drank from his sorrow.

Alejandro spoke to the house and his father spoke to no one. The house drank his father’s tears and held its wooden tongue.

*

Alejandro’s mother had been the most beautiful woman to ever live in that village. There were some women in the village who dressed up more, who spent money on cheap jewelry, but a burro is a burro, even if he wears a silver collar. And all the old women said she had been the best mother as well. Alejandro did not understand how this could be, since she had died and left him—her only child—in this silent wooden house.

But she had been beautiful, this he had known to be true. And even as a small child he remembered how everyone—men and women both—had talked to her, how their voices had become softer when she was around, how they had pleaded so softly, how they had wanted. Felicia, they would call. Come sit with us! Felicia, come talk with us a while!

And she always had time. For the old ones, especially. Alejandro remembered being angry they took up so much of her life.

The other men his father’s age had still laughed about how the beautiful Felicia had hooked him all those years ago. How he had been such a poor fish, but a happy fish for all that.

Every Monday then his father would drive his truck out of the village and across the plain into the forest to choose the wood that he and his workers would turn into furniture and carvings for the shops in cities far away. And Alejandro’s mother, Felicia, had always gone with him. It was the only time she ever left the village. Alejandro never left.

Then one day there were no more trips. There were no more workers in the big workshop snug to the back of the house, on the other side of the wall from Alejandro’s room so that he could always hear the nick and the scrape and the tick and the saw as the beautiful carvings were made.

There were no more carvings, no more words or time for anyone from either of Alejandro’s parents. For that was the day his father had had the accident, and the day the splintered bit of wood had miraculously passed through glass and passed through metal and passed through the heart of the beautiful Felicia.

*

He had heard the old women of the village say how this bit of wood had been like a giant thorn, a thorn that had pierced the heart of Felicia. It was these same old women who had brought all the food to their house the day after his mother had died. They had come in their long black dresses and shawls, their faces barely showing, like large black birds, flock after flock, so many and all of them dressed alike. Alejandro had wondered who they were, where they had all come from. He had not believed there were so many old women in their small village. He saw some come from houses he had not known contained old women before that day.

They brought deep into the darkness of that hollow wooden house great bowls of steaming beans, tortillas, platters of meat, plates of silvery, staring fish, offerings of potatoes, cheeses, breads, and desserts of all kinds. Alejandro had never seen such a feast.

On their table top of tree slabs sanded and joined into a glass-like perfection, the feast had sat a day and then another day, untouched. Sometimes his father would come to the table at the usual time, sit and stare at the soft and gentle spread of food with tears in his eyes, his fingers rubbing the smooth edges of the table endlessly. But he would not eat. Alejandro, too, had sat solemnly, not touching the food the old women had brought, because perhaps this feast was for watching and not for eating.

Instead he had stolen fruit and bread from the local merchants to keep himself alive, nibbling on the small bits as he sat back in the dark and empty woodcarver’s shop.

After a few weeks the stretch of feast softened and ran like yellow wax in the heat. The nuts fell out of the cakes and breads. The fruit rinds blackened, the meat turned greasy and sour, and flies speckled the collapsed mounds like dark garnish. The fish grew thinner, their eyes larger and clouded. Sometimes he witnessed his father staring at the remains, whispering silently to himself. Sometimes he had to fight off the urge to cover the decay with a sheet, thinking it somehow obscene but afraid of how his father might react.

Eventually the flies spread beyond the dining room, gathering in neighbourly groups and filling the house with the first conversation Alejandro had heard in weeks. A sweet stench flavoured the young boy’s dreams. Alejandro expected the beautiful wood of the house to begin to show at least some small signs of this decay, but this did not happen.

*

Again he woke late in the night to the sounds of weeping. He wondered if his father was drinking his own tears, if that was what was keeping the master woodcarver alive. Alejandro missed even the nervous talk of the flies.

But then the weeping suddenly stopped, and he sat up in bed, trying to control his breathi

ng. A rustling came from the dining room, and he immediately thought of rats though he’d never seen one in their house. He crawled out of bed and walked slowly down the dark hall, clouds of flies separating on either side of his face like a lively and murmurous beaded curtain. He clamped his mouth shut. Flies don’t enter a shut mouth.

His father sat slumped over the ruins of the table (Alejandro had to remind himself that it was the feast in decay, and not the beautiful table itself). His father stared off into the distance, as if waiting. The ragged shadows atop the table shifted, then moved with a scrape of claw and a slide of tail, slowly trundling off into the deeper black like props being moved about between scenes of a play. Occasionally some of the odd baggage revealed itself in a sliver of moonlight from the windows high in the wall: pale and mossy things, red-encrusted pink softnesses, sharp-edged, exposed bone, congealed liquid splatters, all kinds of obscene things Alejandro thought best buried, best all forgotten.

But to all this there was a strange quiet, a seriousness, unlike anything he’d witnessed outside a church. And then Alejandro wondered if he was in a kind of church here, watching the processional. The ushers were guiding the people to their seats. The props were being moved about. Someone hushed a talker in the back pew. Someone was weeping.

His father jerked out a hand desperately and tried to stuff some of the moving food into his mouth, the great black backs of shiny insects drifting over his face like crude widow’s lace. Kissing the food, spreading it over his mouth and cheeks for comfort. For communion. “Felicia … Felicia …” He mouthed the name over and over, but would not release it.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

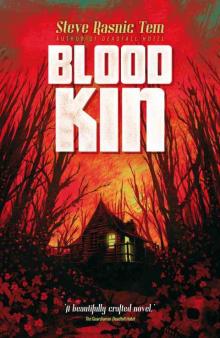

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin