- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

The Man on the Ceiling Page 9

The Man on the Ceiling Read online

Page 9

Christiana, Katy, Mya, and Sophia, the great-granddaughters my father never knew, also live in this interior space. It’s not impossible that he met them there, playing in the brush-covered car.

Christiana would have regarded him impassively. “Impassive” is one of the things she does best, along with “silly” and “pensive” “I know who you are,” she might have announced. “I said your picture.”

As long as this great-grandfather of hers kept his distance, Mya would have allowed herself to be interested, especially if he sat in that humped car in the woods. But if he’d approached her, she’d have tensed. If he’d tried to take her in his arms, she would have honked the horn.

The baby Sophia, having more recently than the rest of us been in the world that car came from, might just have been able to focus on him for a second or two before something else in this world caught her attention.

From a step or two away, Katy would have taken him in. She’d have pointed with all four fingers of the hand whose thumb would have been in her mouth (which, she will tell you forthrightly, is for the purpose of keeping her safe) and would have demanded again to know: “What’s that boy’s name?! What’s his name?!”

Chapter 6

Elephant Soup

Not very obsessively but with small, solid pleasure, Steve and I collect storyteller dolls. An icon from the Southwest United States, storyteller dolls are really sculptures, sometimes plain terra cotta or whitewashed white, but usually brightly painted, most commonly palm-sized but occasionally as tiny as the tip of a thumb and once in a great while as massive as boulders.

There’s always an adult with mouth and eyes wide open. There are always children, clambering, playing, cuddling, listening attentively with miniature hands in miniature laps.

Sometimes they are specific, with detailed costumes and well-defined facial expressions, the faces of the attached children individualized. Sometimes the children’s faces so mirror the storyteller’s that the narrative they’re all engaged in seems to be one of those we necessarily tell ourselves generation to generation. Sometimes all the faces are blank.

The price of a storyteller doll varies depending on size, intricacy of detail, and, tellingly, the number of children. In a sense, too, the price varies according to the story being told.

Do the children have a part in creating the stories for the storyteller to tell them? If a tree grows in the forest and there’s no one to tell its story, can it be said to grow? For that matter, can it be called a tree?

Such questions have to do with the nature of the language we use to symbolize a thing, not with the thing itself. At least, that’s true about trees. A tree wouldn’t be called a tree—wouldn’t be called anything—without human words, but it doesn’t depend for its existence upon human perception of it. I’m not so sure about stories.

Some stories we tell ourselves “for our own good.” We tell them to our children, who are apt to call them “lectures”—their word for the unnecessary and irrelevant. In response we are apt to rename them “under-appreciated.” I imagine the stories told by storyteller dolls to be neither unnecessary nor under-appreciated.

In more abstract versions of the dolls, the children’s heads are like growths on the storyteller’s body, great or tiny distortions of flesh, mutated receptors directly connected to nerves and bloodstream. The storyteller’s mouth is like a yawning wound letting loose a necessary howl from that dark country just the other side of flesh. The storyteller doesn’t particularly want to tell the story, but is compelled to do so. The children would rather be playing, but their horizons have fused with the teller of the tale.

We tell stories because we need to, and because our children need us to. I think I was a storyteller long before I was a mother. I think I tell stories because of all the relationships in my life—because I was a child of my particular parents, because of how I see, because of other lives that swirl and eddy through mine. Because of Steve. And, of course, because of my children.

My parents had put together for me little set pieces out of their lives, which they recited in the same way every time so as to gather the power of refrain or ritual or magic spell. I believe now that the stories had been selected and edited, all but deliberately, to illuminate and to limit illumination. I think both of them yearned to be known, especially by me, their only child, and both were horrified by the prospect. So they put forth truncated and stylized narratives that required me to meet them more than halfway. I have not always been willing to do so, but I am now.

The stories were selected and arranged by theme, and the themes of my parents’ lives were remarkably similar. Each, for instance, had a single innocent, amusing tale with sinister undertones: the knob on the tree that the child who would be my mother routinely scared herself into thinking could be somebody lurking; the rich golfer offering to “adopt” the teenage caddy who would be my father. Each had one coming-of-age tale: my mother’s first job away from home in the big city; my father’s cross-country Depression-era trek in search of work; these were synopses without supporting detail, so my imagination doesn’t have enough to go on.

Each had a litany about the death of a young mother, language become meta-language that took the story deeper and also kept it distant:

“I was seven years old when my mother died. They told me, ‘Big boys don’t cry,’ and I didn’t. I didn’t cry.”

“The doctors told my mother to drink cow’s blood and eat raw liver, but she couldn’t do it, and so she died.”

There were three or four stories apiece about a wicked stepmother and a younger sibling singled out for particular abuse. Throughout the years each made recurrent mention of one and only one childhood friend. The story of how they met was always collaborative, my mother’s part the romantic frame, my father’s the gentle jokes.

All my life I have worked to know my parents better (except for those periods when I wished I didn’t know them at all). Most of the time self-referentially, sometimes even wanting to understand them other than in reference to myself, I have searched and struggled and fought and waited, and I’ve come up with ways of thinking about them that may or may not be factually true. Truth, like creation, seems to me to take place at the intersection between sender and receiver.

So I say about my parents that each of them loved five people throughout the eighty years of their lives: their mothers, their fathers, their little sisters, each other. And me. For their other siblings they nurtured disdain unleavened by anything I would call love or even filial affection. Their friendships were not allowed to take deep root. They did not claim their grandchildren.

For many years I chafed at, mocked, resented, wrote about how constricted they were, how inaccessible, their inability or unwillingness to take even the most minimal emotional risk. Until it dawned on me that loving the five of us could be cast as an enormous risk, a breathtaking act of courage. This framing device, this change of genre or shift in point of view, allows for quite a different story, using the same facts to arrive at a different and no more or less truthful truth.

Framing has to do with what we make things mean. This is a story I often tell about Steve:

The Elephant’s Ear

The storyteller watched all the children cuddling in his lap and climbing on his back, but he was especially alert to the wan, fragile little girl crouching on the kitchen chair. He took a calculated risk. “You know what that soup’s made of, don’t you?”

Having learned to expect treachery and horror from the world at large, not knowing yet what to expect from him, she stared at him, spoon halfway to her mouth. “What?”

“Elephants.”

“What?!”

“Yep.” He nodded solemnly, continuing to eat his cream of mushroom soup. “Elephants.”

“Huh-uh.” Now she was staring at the lumpy gray liquid in her bowl, eager to play this game with him, not sure it was a game, thinking those could be pieces of elephant in there.

“Yes,” he persiste

d, straight-faced, vigilant so he could gauge how far to take the fancy. Playing like this, he could sometimes make her laugh, a rare and breathtaking sound, but if he went just a little too far she’d dissolve in tears and he’d feel as if he’d harmed her, as if the play had turned into abuse and the fantasy into a lie. “See? Right there, that’s part of the elephant’s ear.”

Later, Veronica would tell her father that elephant soup was one of the ways she’d learned to trust.

Later, he’d watch her imagination develop into a sudden intense love of reading, a quick wit and enjoyment of word play, a childlike but not childish engagement with her own daughter in conversations with imaginary friends and scenes of elaborate role assignments (“I’m the Mommy, you’re the baby! I’m the girl, you’re the puppy! I’m the vampire-slayer, you’re the vampire! Okay?!”). Observing how healing this was for her, he’d allow himself a small, careful satisfaction that he’d given it to her, and she would understand the gift and be grateful and know to pass it on.

But at the time he first told her about elephant soup, she was seven years old, and he was newly her father, and adults had done worse to her than feed her chopped-up elephants, and she didn’t know what to make of it. She took another spoonful, saw for herself the lumps that could be pieces of tail and trunk and Dumbo ears, made a face and dumped it back into the bowl. If it was mushroom soup, she might like it. If it was elephant soup, she didn’t dare eat it. A cautious child by nature and circumstance, she opted for self-protection over this particular form of sustenance and pushed the bowl away.

Later she’d insist that the elephant story had ruined mushrooms for her forever. A small price to pay, if you ask me, even if it were true. We all knew there were other reasons she came to hate mushrooms, such as the hormonal changes of pregnancy that made them and a host of other foods nauseating. But this was her contribution to the elephant soup story, the way she collaborated to construct a family legend.

And, of course, it’s absolutely true.

Daughter of the daughter who consumed the story about elephant soup, Katy is a born storyteller. Long before anyone could understand her, she had joined the oral tradition: telling stories, acting them out, snatching pieces from the big mysterious world and spinning them into her own truth to bridge and interpret and expand, discovering and rediscovering how reality puddles, the fundamental process of creation happening before our eyes.

The moment she could talk she was interrogating and exclaiming. In one tale, “Shark?” and “Fish!” and “Water?!” were the only intelligible words, but she used her whole self to embody the narrative. In bright pink pants and a lacy shirt, wild blonde hair in the dapple of spring leaves, she plunged as if underwater, feinted, swam, gasped for air, kicked to get away, dived deeper. Enthralled, we followed her. We had a pretty good idea what she meant. When she seemed to have reached the end of the story, we applauded, often prematurely, for there is always more to tell.

Did we, in fact, know what she meant? Was the story we made up for ourselves, out of the cues she gave us and those we added on our own, the story she had in mind? Was my story the same as Steve’s, the same as her mother’s? Was she the storyteller or the child sitting at the storyteller’s feet? Are we?

“Omigod!” Her eyes are wide, her hand over her mouth. She stands motionless in the middle of the room; she is not often motionless. “Omigod!

There’s two of you! And two of me!” She begins to back away.

A chill runs through me. I think of childhood schizophrenia; this is an occupational hazard of my work with the families of disturbed kids. She does not appear to be playing. I say her name and “What do you mean?” in a clumsy attempt to bring her back to reality if, indeed, she’s escaped it.

“Oh! My! God!”

She is utterly convincing. This is making me nervous.

Then she shrieks with laughter and darts away yelling, “Don’t chase me! Don’t chase me, Baba!” which means I’m supposed to chase her. When I catch her under the dining room table she throws her arms around my neck and we giggle together, transported. Later her mother assures me that “Omigod! There are two of you and two of me!” is dialogue from an Olson twins movie. I’m relieved, bemused by my own credulity, and thrilled by this child’s willingness to enter fully into Story.

What I’m about to do, a season or so later, is a risk. But she’s been talking about death for months, asking what it means, worrying that she’ll die and, worse, that Mommy will, just having encountered the fact of mortality and struggling to come to terms with it for the first of what undoubtedly will be many times in her life. So when she asks, “Can I see her?! Can I hold her?!” I glance at her mother, who nods tearfully, and I bring in the body of the yellow cat Cinnabar who’d been in our family twenty-two years, almost as long as our family has existed in any form at all.

Our eldest son Chris saw her born. Ten years old, he’d just come to us, having taken “you can’t trust anybody” as the theme for his life story, he would teeter for many years on the bridge between anger and love. Being present at the kittens’ birth didn’t work a miracle, but I think Cinnabar was a constant for him, an emblem of “family,” less demanding than the constancy of his dad and me, a story in its own right and a metaphor he was free to accept or reject.

That, of course, is my story of my son and Cinnabar, not his. I hear him tell his own children, “I’ve known Cinnabar all her life. I saw her born.” That’s all he ever says.

Cinnabar gave us many stories. I doubt she intended to. She was a cat. Whatever storytelling might go on in the feline sensorium, I’m not species-centric enough to imagine it’s humanoid. Her gifts to us are our stories, and as long as we remember that, they’re absolutely true.

Cinnabar used to lie on our bed in a golden pool. Our youngest child Gabriella couldn’t leave her alone. She’d poke at her. She’d tug at her tail. She’d put her nose to Cinnabar’s nose, blow on Cinnabar’s whiskers, brush her fur backward. We warned her. With small growls and hisses, tail twitching and stalking away, Cinnabar warned her. The little girl persisted, perhaps exploring power, respect, alien sensitivity, the place where stories are born at the intersection of one life with another. Or perhaps just being stubborn.

Whatever the impulse, she wouldn’t stop pestering the cat, and one day Cinnabar had had enough. Quickly and cleanly, she stuck a single claw into each of Gabriella’s tender temples, just as cleanly withdrew them. As if she knew this was a young one who needed at the same time to be taught a lesson and to be protected, she didn’t go for the eyes, didn’t scratch, didn’t even draw blood.

But our daughter got the message. Shocked and tearful but not really hurt, she backed off, and she took the first step that day toward learning how to be with Cinnabar on Cinnabar’s terms.

At Cinnabar’s grave, our daughter, tall and beautiful now and insightful when she allows herself to be, delivered the eulogy, her story of the story of this beloved animal: “She was a good kitty. She taught me an important lesson.”

I’m not sure Gabriella actually remembers Cinnabar’s teaching. But her dad and I have told the story so many times it’s become her story, too, more textured and resonant for having been passed along.

“Why is she so cold?! Why is she so—”

“Stiff,” supplies the child’s mother, who has loved this cat as long as she’s been our daughter.

“Why is she so stiff?!” The small hand lifts the paw and lets it fall. It moves like something inanimate. It is something inanimate.

“That’s what death is, honey. She’s not in her body anymore.”

“Where is she?!” A reasonable question.

“I don’t know. Nobody knows.”

“Can I see her face?!” The pink towel is pulled down, revealing the sweet, stiff, furred face, slitted yellow eyes, pink nose. The child gasps but does not turn away, knows to go forward into her sorrow. “Can I hold her?!”

When she sits on the couch to receive the slight body,

her feet stick straight out the way her mother’s used to. Struck by gratitude and loss and the accumulated power of repeated patterns, I am aware of stories passed down through generations. A story is being passed down right here and now.

I put the swaddled body into her arms. She cradles it, not the way she might cradle a doll or a baby brother or a living pet but exactly as she would cradle a loved, dead creature. “Can she feel me pet her?!”

“No. She can’t feel anything anymore.”

“Why?!”

“Because she’s dead.”

“Why she’s dead?!”

I take a deep, ragged breath. “Because everything that lives has to die.”

“Why everything that lives has to die?”

“I don’t know.”

“Will you die, Baba?”

“Yes.”

“Will I die?”

“Yes.”

“Will Mommy die?”

I meet her gaze and tell her the truth. “Yes.”

She opens her mouth, throws back her head, wails. I stroke her hair, but I don’t tell her to stop crying or that everything’s all right. Her mother doesn’t, either, though it costs her. After a few moments the child’s anguish subsides, and she takes one hand away from the cat’s body to tug at my fingers. “Sit here by me!” Crying now, I sit where she tells me to sit. Her mother stands beside her, crying. She looks from one of us to the other, alarmed but not in the panic that usually strikes her when her mother cries. “Why everybody’s crying?!”

“Because that’s what we do when we love someone and they die. We’re sad, and we miss them, and we cry.”

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

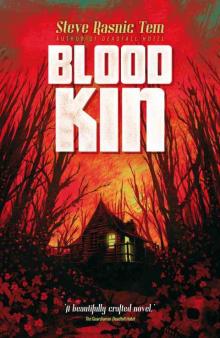

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin