- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

Celestial Inventories Page 12

Celestial Inventories Read online

Page 12

“She drove. We don’t drive. What can we do?”

“You drive? Sure, you can drive. Say you can drive! Drive us away from here!”

“I don’t know what happened. Do you? The mountain fell up, the mountain fell down, I don’t know what happened! Can you drive?”

“I have a new outfit. Do you think it’s yellow? I won’t tell, unless you ask me. I think it’s pink, yeah, I think it’s pink.”

“I’m hungry. We can go now, I’m ready to go! Dinner time! Say it after me, dinner time!”

“Are we going, soon? Can we take Granny? Do you have to stay here?”

“I don’t want to leave Granny here!”

“The ground’s all broke. I didn’t do it. It was an accident. Accidents happen and somebody gets hurt. We had an accident today!”

“I need the bathroom. Where’s the bathroom, John?”

“His name isn’t John.”

“Where’s the bathroom, John?”

“His name isn’t John!”

“Where’s the John, John?”

They all laugh. The one on the left starts coughing, and can’t stop coughing.

“No, I mean it. I need the bathroom now!”

“Are you crying? I’m not crying.”

“That man is yelling! Why is that man yelling so loud? He hurts my ears.”

“He hurts my heart.”

“He’s hurt! He’s mad! He’s mad that he’s hurt!”

“What happened? Don’t cry!”

“That man is crying! I’m not crying!”

“Why does stuff keep happening? I didn’t do anything wrong. Stuff keeps happening!”

“Why does that man scream? I want to scream.”

“See, I know how to scream.”

“Stop screaming!”

“We don’t know what happened. Is it a secret?”

“What happened? I don’t want to be here! I don’t want to scream!”

“Get us out of here! Help! We don’t want to be here! I don’t want Granny dead!”

“Are we going to die?”

The three sit quietly, blinking. They look at each other. The man in front of the truck keeps screaming, gradually going hoarse. He stares at you, then starts screaming again with sharp, staccato, raspy screams.

“It happens and happens and happens and happens.”

“And then there’s just nothing.”

“Nothing but rocks and dirt and dirt.”

“And nothing. Just nothing.”

“But maybe some cake. I like cake!”

They all laugh.

“Okay, okay. We’ll just sleep now.”

The three close their eyes tightly, lids creased from the effort. They are quiet.

*

The sun has begun its drop. It’s going to be a cold one tonight. It’s always ten to fifteen degrees colder up here than in Denver. You’re not wearing your jacket. It’s in the truck. But the truck, of course, is gone. As far as you are concerned, the truck never existed. This is the first day of the world, and survival is always the first chore on the first day.

*

Friday, 2:30 PM

1968 Light Green International Harvester Travelall

It looks like a giant metal lunchbox with wheels, pushed to the side and severely tipped, out of line with the others. But no more out of line than when it was driven on the highway, part van part truck part station wagon part SUV, poor cousin to them all. It looks undriveable, but it probably always has. Dirty brown rust creeps up the sides in long, meandering fingers. The tires are smoke-grey and cracked. The yellow dust from the morning sticks to the windows like a coat of mustard.

From inside the car music squeals and bellows, getting louder when the driver’s window eases down to expel another cloud of smoke.

Sharp highlights in the metal fenders scraping the eye the closer you get. You almost expect quills to come flying, or some evil scent cast out of the exhaust pipe. But the clouds are starting to come in, and you know it won’t be that long before the sun drops behind the last distant ridge.

As if the machines up top are waking from their naps their noises suddenly sound more aggravated. Progress, some might say, is being made. You wonder if they’ll be able to work after dark. If they will dare.

The Travelall’s window grates coming down again, and you think of all that grit fallen into the mechanism, scratching it into ruin. “Stop right there!” from inside a cloud of smoke. “Tell me what you want!”

You try to speak but the words aren’t there. Neither are any sounds further evolved than a rasp. You wave your hands helplessly, as if falling over backwards.

Your mime almost causes a real fall. Your ankle tips and you overcompensate to escape the pain.

Smoky laughter from inside the Travelall. You wonder, briefly, if there’s anyone actually inside. Maybe the car itself has a voice.

“Okay. Get in. You look harmless enough. But I warn you—I ain’t.”

You creep to the passenger side, the ground here feeling the most unstable of all. You think you hear the world cracking under your boots. The passenger door pops open just as you get there. Smoke pushes out like a trapped storm cloud. You close your eyes and make yourself sit down. A gorilla’s arm brushes past you and strong-arms the door, shutting you inside with hot smoke and animal stink.

“The name’s Rake. And you?”

You discover you can’t open your mouth. You try to speak with your eyes but you know that you have no talent for it.

“Oh, I forgot. Avalanche got your tongue. Snick snick.” Like scissors, but it’s the sound he makes when he laughs.

His face has too much hair. Hair fills the planes of his cheekbones, spills down his chin and neck. There’s even hair, though not quite as thick, just below both eyes. You don’t think you’ve ever seen that before, outside a comic book.

“I’ll only warn you once. Don’t look like you’re gonna try anything. Then follow that up, by not trying anything. Look at the glove compartment. Don’t open it! Just look at it. I’m not going to show you what’s inside. I can’t show you what’s inside. I’m going to let you imagine that, and while you’re at it, imagine what will happen if you do anything wrong, and I have to open that glove compartment.”

You stare at your hands. You tell them not to move.

“Meet the wife and dog,” he says.

Trash on the floor: Reese’s Cup wrappers, a Pepsi can, a letter or two, covered in chocolaty shoe prints. The rusty glove compartment door.

“Behind you, halfwit!”

A twist in perspective: shaky car hood, interior light with no lens, stained upholstery peeling off the metal interior frame and hanging down. Then so close that he could bite off your face: a huge black Lab, directly behind you the whole time. Stink a little less than that on the man.

A twist to the other side: there, back in the far corner near the double doors, a woman ten years the man’s junior, at least, her knees pulled up to her chin, dirty straw hair scratched down over her forehead.

It’s then you realize the seats have been taken out, the interior filled by a striped mattress, flowered with brown rust stains.

You turn back around. The man is stroking the black ball fixed to the top of the long, crooked gearshift. “You get on outta here,” he says. “If you ever find your voice, you tell the others what you seen. And what you didn’t. I just wanted you to see the glove compartment. I just wanted you to think about what might be in there.”

*

Friday, 3 PM

1974 Honda Accord, Green

Both headlights and front grille missing, the Accord sits back on its rear tires like some bloodied circus animal, front tires shredded in the effort to stop the inevitable, fluids dripping out of the engine, a spreading pool on the chewed pavement.

Once you’re inside, the car bobs from wind or your own weight. Dark grey upholstered ceiling. Dirty black rubber mat jeweled with broken windshield. Torn soft grey seats, stuffing erup

ted in white tufts from multiple rips. But no driver.

A glimpse through the missing windshield: searching the surrounding grass, pavement, for an ejected body.

A small moan.

A hurried gaze back into the rear of the car, behind the driver’s seat, the body thrown there, a man about thirty, maybe a little older: compressed from the collapsing rear-end of the car, squarish, his shoulders squeezed up into a confused shrug: the man has been reshaped into a suitcase.

Suitcase Man opens his eyes suddenly. The left eye socket is full of blood. Both eyes gaze forward, determinedly focused.

Suitcase Man opens his mouth, or maybe it’s just the light changing. You can’t tell. There’s so much blood.

“I couldn’t stop. The car just, jumped. I could feel myself, floating. I must have, blacked out. I woke up sitting here. I couldn’t remember if I’d been driving. I was in the back seat! How could that happen? I kept thinking how lucky I was that my little girl wasn’t with me. My wife died a year ago, and I have to work a lot out of town. My sister takes care of her. I’m supposed to see her this weekend. I hope this doesn’t get in the way.”

Your own hand suddenly appears, rising in the space between you like an apparition, a magic trick. The arm it is attached to is so caked with dark blood and grime it virtually disappears in the dimness, so that the hand appears severed, moving separate from the body.

Suitcase Man’s mouth is open, and he is crying without sound. The hand floats toward Suitcase Man’s shoulder, and touches it ever so lightly, as if to comfort, and Suitcase Man’s mouth suddenly finds its sound as it fills with a scream.

The face of Suitcase Man darkens, recedes into the shadows, and closes.

A shaky glimpse through the open car door: dark-stained gravel, tennis shoes scuffling past. Somewhere a child cries. The light becomes painful as you get out.

*

Friday, 3:20 PM

2007 Chevrolet HHR Panel Truck, Brown with Yellow Trim/Lettering

No visible damage except for a shattered front left headlight. Debris has slid beneath the front tires, filling the space under the axle, raising the front end almost a foot above the roadbed. A rich, caramel brown colour, the side panels are heavily ornamented with yellow scroll work and the elaborately lettered “Johnson’s Furs” and “Repair, Cold Storage, Delivery” and “Denver’s Finest.”

The panel truck is still running. Its sound is a soft and musical hum, in contrast to the construction equipment up on the hill.

The right turn signal blinks steady yellow. Where does it plan to go? There is nothing on this side but a couple of feet of torn road, followed by air.

The passenger door opens a few inches. The speaker is hidden: “Can you make it up those rocks? Climb in—I have bottled water. Hurry now—I’ve got the humidifier running. I can’t leave the door open for long.”

You glance off the side, then step, step, the sharp clink of useless keys in the right front pocket. The sky waves you on, back and forth. The caramel panel truck appears to rock in an attempt to free itself, and leap off the side, but you know it’s an illusion caused by your run.

Feet slide sideways on the small incline of gravel and sand. The right front wheel dips suddenly, spitting a fist-sized rock past your thigh. You hesitate, then with a single stride reach the door and jerk it open, slamming it shut behind you as you tumble inside.

“Thanks for being quick about it,” the speaker says, offering up a small bottle of Aquafina in your direction. You take it—he’s already loosened the cap. You finish the job and take two long swigs, cap it.

It doesn’t taste like water. If anything, it tastes like stale air.

The speaker nods. His uniform is a darker brown than the outside of the panel truck, but with the same yellow designs and lettering. His hair is a shade lighter brown, a pleasing complement. “My boss is crazy for the stuff. He keeps a cooler behind the seats, full for the mountain runs.” He turns his head, staring into the side mirror. “Everybody okay back there? I have to keep the vehicle running to keep the humidifier going. So I’m not just wasting gas. In this climate the furs dry out quickly. My boss says the clients pay good money to keep that from happening. They store them cold, then they deliver them cool and humid.” He looks out the windshield, his hands sliding up and down the steering wheel. “Coats, jackets, purses, hats, mini-vests, boleros—that’s a kind of vest, but with sleeves. Fox and mink mostly, all kinds of colours. Expensive. You can only open the doors from up here—it’s all electronic.”

In the distance the clatter of equipment changes tone, as if it’s running down. He looks at the gas gauge.

“But I don’t want to run out of gas, either. Any ideas?” He looks at you directly. The shaking isn’t the panel truck, or the ground, you remind yourself. It is your own head, signalling a negative.

The whites of his eyes become more prominent, their centres blacker. “You’re thinking I won’t need the fuel, right? We may get out of here, but our vehicles certainly aren’t.”

He stares at the wheel, the gauge. “My boss is gonna die. We’ve got some real expensive furs in here. But he probably has insurance, right? Not such a disaster, but the customers, they’re rich people up in the ski towns, and they get steamed when everything isn’t perfect. That’s where I was headed. They want their furs in time for ski season, all fresh and clean. My boss calls it rested. ‘They like their furs rested,’ he says. But they’d probably stop using him, even when it’s an act of God.” He pauses. “I mean, that’s what it was, right? An act of God?”

He abruptly turns the switch. The humming stops. And with it a subtle vibration you hadn’t even realized was there. He stares at you, eyes wide. “I make this drive a couple of times a year. Nothing’s ever happened before. If they stop using him he’ll be ruined.”

He turns the ignition, and if not for the sudden change of atmosphere in the cab you’d not know the vehicle was running again. A rivulet of sweat rolls off the man’s cheekbone. “It gets pretty hot in here. See, it’s set up with a humidifier in the back, and an air conditioner up here, because the air conditioner dries them out. But the air conditioner doesn’t work that well when the humidifier is on.”

He stares, then grins. “So I guess I’m screwed.” Serious again, he says, “That’s why I didn’t get out and distribute water to everybody. I mean, not just that I need it myself. But because I can’t leave the truck. All these expensive furs, you see, they’re my responsibility.

“But you take a few bottles, okay? Give them to the ones what really need them.”

When you’re a few yards away you realize you forgot the offered bottles of water. But you do not go back.

*

Friday, 4 PM

2006 Chrysler Sebring, silver convertible

No signs of a driver or passengers, but a few bloody handprints on the dusty upholstery. The front seat is full of stones, 3 to 6 inches across, scattered clumps of dirt, and a small tree complete with root ball, upright in the passenger seat, the leafy head peering over the windshield, on the lookout for perils.

*

Friday, 4:15 PM

2005 Toyota Yaris, red

The driver has a cut on his forehead. The seepage has turned his blonde locks red in front, so it looks like he has dyed just the tips, or perhaps he is a redhead who has bleached most of his hair, but interrupted, he was unable to complete the job.

“Please don’t bother me now,” he says. “I’m fine—I trust everyone else is as well. I just want to finish my book before help arrives. See, I’m almost done.”

He holds up a worn, dog-eared copy of AZTEC, by Gary Jennings. He grabs the last few pages—thirty or so—between thumb and forefinger and gives the book a shake.

*

Friday, 4:45 PM

2005 Dodge Caliber, silver

The woman, half-asleep, has her eyes covered by a glove. She peers up from beneath an empty thumb. She waves you away.

Where is everybo

dy? You can hear the rescuers talking up on the ridge overhead. Occasional, inappropriate laughter. You imagine that’s the way angels sound when God isn’t watching.

*

Friday, 5:30 PM

2004 BMW Z4, grey

Within a dozen feet of the vehicle you can hear the argument: the woman’s voice and the man’s voice filtered through the closed windows into something more formal, more musical than was no doubt typical for them. You can’t make out the words, but the gestures seem all too familiar, the face contorting with a raised fist, the head-shaking sneer when something beyond belief has been said. But watching closely you can see a private etiquette: they are taking turns with their outbursts, each waiting patiently as their partner finishes. They don’t even know you’re there, and before they have a chance to see you, you slip away, like a spirit on the road from here, to there.

*

Friday, 6 PM

1999 Daihatsu Charade, orange

You know there is a car here, was a car here, only because of the orangeish bits of metal, which match none of the other vehicles you have seen. The largest bit has the Daihatsu symbol still affixed. A river of stone has erased most of what rested here. Wedged between two stones you find a single, shiny word in more or less permanent script: Charade.

*

Friday, 6:30 PM

1978 Lincoln Continental Town Car, black

It sits with all windows rolled up. Sleek, huge, an older kind of luxury. The engine isn’t completely silent—there is a subtle whine, an intermittent tick, in its steady bass—but that only magnifies its perfection. You’ve seen no one leave, or enter, this vehicle since the disaster. Now and then a window has rolled down an inch, maybe two. Now you approach, anxious, short of breath. You can hear yourself, and you’re surprised by what you hear.

A back door opens. You’re surprised when the cold air hits you. A man with white hair slides his head into view within the interior. “Welcome,” he says. “We were wondering when your travels would bring you to our little neighbourhood.”

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

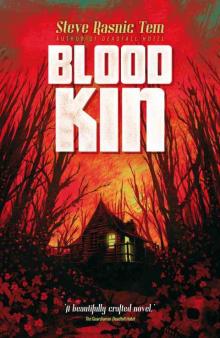

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin