- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

Celestial Inventories Page 13

Celestial Inventories Read online

Page 13

You hesitate, but the cool air makes this invitation irresistible. As you step within the angle of the open door the gentleman slides over to make room. However unlikely it seems, you feel important.

The door clicks shut behind you, smooth as a well-greased vault door.

“Care for some wine, some champagne?” He hands you a glass. He gestures toward a small bar mounted to the back of the front seats. A line of bottles await. You are suddenly incredibly thirsty. But then you remember all the pills you consumed earlier, and you shake your head.

“We have fruit!” An eager, youngish voice from the other end of the back seat. The gentleman leans back, and the young woman juts her chin forward, and in her outstretched hand, six sections of bright, glossy orange. “These oranges, well, they’re to die for.” She emits a distinctly unladylike snort.

You accept, and with the first bite you are in complete agreement.

“Our rescue is proceeding smoothly, I assume?” An older woman in the front, peering around the edge of her seat, showing one eye.

You nod dumbly.

“Very good. Clarisse will put together a bag of oranges for you.”

When you leave the cool air you have the bag clutched in your fist. You hold it slightly behind your back, hoping no one else will see.

*

Up on the ridge the rescuers are arguing. It’s too dark to see, but there are no more sounds of machinery and you assume that is not a good sign. There appear to be many more people up there now. Vans. Emergency vehicles. The squawking of two way radios.

You have only one more vehicle to check. You do not know what you will do with yourself after that. You have been going over every inch of ground, counting the ejected bodies, erecting a pile of stones beside each body. You hadn’t realized there were so many. They had been disguised by the rocks and the other debris. And you had been focusing on the vehicles.

It’s going to be very cold tonight. You feel very bad about leaving the bodies out here in the open, but of course you know they are past feeling anything.

*

Friday, 7 PM

1999 Subaru Outback Wagon, white

The car is on its right side. Approaching from the undercarriage side you hear the music, something soft and folksy, and dim. As you’re climbing you see dark red and purple sky, the dead car, sky again, the silhouettes of abandoned construction equipment up on the ridge. Dark sky. Your feet slipping, finding purchase again. The dead car, with its driver’s side window open. But where’s the driver?

You can look down through the driver’s window now into the interior of the car. The overhead dome light is on, and that’s enough to allow you to see his legs, the side of his hip, but his head is somewhere below. He’s still strapped into his seatbelt, and he’s twisted around, hanging there.

“Hello? I’m caught,” he says. “Hello, I’m caught. My leg’s hung up. I don’t know, something went into my leg.”

You move around, get a better view. Then you see the piece of metal, where it enters, just above the knee. The pants are soaked a dark colour, the wound still dripping, running down the metal, pooling over the scattered magazines down below the head you can’t see, a dozen or more magazines—issues of People, Us, Entertainment Weekly—covering the glass at the bottom of the car, what used to be the passenger side window, now cracked, sections missing, the holes plugged with the blood-soaked magazines.

“Can you see? Can you see? No, don’t tell me. I think I’d rather not know the details. I know it’s bad—that’s enough.”

You want him to turn off that music, but you restrain yourself.

“I wasn’t even supposed to be up here. These contracts needed to be delivered up in Aspen. Nobody wanted to do it. I didn’t want to do it. It’s my daughter’s sixteenth birthday today, and I didn’t want to do it. So why did I volunteer? I’m always doing stupid things like that. Always have.”

Everything is quiet now. You look away, across to the other vehicles. Almost dark. A man stands by one of the cars, gazing your way. No other movement.

“My point is I didn’t have to be here.” You can’t see his head, so you gaze at the magazines, slowly darkening with blood. Pictures of starlets, singers. Britney Spears. Anna Nicole. “But I came. I delivered the contracts. Then I realized I’d forgotten to pick up my daughter’s birthday present back in Denver. I can get it tomorrow, but that’s not the same is it? She loves magazines, she loves reading about the stars, you know? She knows as much about their lives as, well, her own. And she worries about them. She reads about the troubles they’re having, and she goes on the internet everyday, searching, reading, until she finds out that those troubles are over, or that they’ve changed into some other kind of trouble. So I stopped at a drugstore and picked up all these magazines. She’ll love them. And then I can pick up her real present tomorrow. Wasn’t that a great idea?”

He falls silent. The dark is close—they’ve turned on work lights up on the ridge, but they’re not doing any work, and very little of that light spills over onto the wrecks below. But here you still have the dome light, and what little it can illuminate inside the car.

“If I hadn’t come up here. If I’d remembered her present. If I hadn’t stopped for these magazines. I wouldn’t even be here. Isn’t that crazy? And now I’m going to be late. Anyway.”

*

You’ve curled up beside the Subaru. The driver stopped talking hours ago. The dome light burned out. You can hear someone moving out among the vehicles, but you can’t see them.

You were never very good at waiting. You were always too jittery. It’s so very cold out here.

“Here.” A voice out of the darkness. Suddenly his face appears above you, hovering like an angel’s. It’s the fellow from the fur van. He is handing you a small, dead animal.

“It’s a bolero,” he corrects you. “Red fox and mink. Reversible, not that that matters a damn. It’ll help with the cold.”

He sits down beside you. He is wearing a full length coat. Sable, you think. You think he’s been crying, but you say nothing.

*

Saturday, 6 AM

When you wake up you believe you are being eaten by a small animal. You scream aloud and try to tear it off you, then remember it’s the fur thing the delivery man gave you the night before. You look around. The delivery man is nowhere to be seen. The day is warming up, so you take the bolero off and toss it aside. All around you the bodies are adorned with fox and mink, red, black, brown, and white furs. It looks as if a hunting massacre has occurred here overnight.

You walk down the line of wrecked cars. The man from the Travelall is standing beside his vehicle, hiding his right arm behind him. He waves with his left and grins. A stylish fur stole is wrapped smartly around his neck.

There are a great many people up on the ridge, silently watching you. Camera lens flash. Soft spoken narration. There is no other movement. No signs of progress on the rescue road.

All around you the world groans. A buzz of excitement. A sudden rush of movement up on the ridge.

You walk by the green pickup. The young women wave gaily from the back, looking beautiful in their new fur clothes.

You pause at the torn edge of the world. You get down on all fours. There is a sharp barking from the distant electric megaphone, but you cannot understand the words.

You crawl over the edge and begin your descent.

You hear yourself groaning, and an answering groaning from the broken heart of the world.

Yellow blast of light and sound. Skies of dirt and stone. Random, brightly-painted metal, glass, bits and parts passing impossibly one through another. The backwards screaming thunder of the world’s pain.

THE

SECRET

FLESH

The stimtech moved her wand slowly over his son’s quiescent body. The tubes that ran into Mark’s neck and chest were well-hidden. Jim could detect them only when the boy’s chest had risen to its full extension, and the

re were slight linear shadows beneath the skin where the tubes pulled against the flesh.

She was a small woman: narrow hips, flat waist; he thought of Tinkerbell. She held the bar motionless above the bridge of his son’s nose. Mark’s left eyelid opened slightly, exposing a narrow crescent of bluish white. Jim’s stomach tightened as he stared at the small sliver of eyeball. He tried to swallow away the bitterness rising into his throat. But the bad taste was the only thing preventing him from screaming at her.

As she moved the thin edge of the bar down from the eye, the left cheek drew in slightly, causing a vague, lopsided smile to crease Mark’s little boy face.

“He is left-handed. Am I correct?” she asked.

Was, he thought. Jim nodded, then realized she was concentrating too closely on his son to notice. “Yes. He wanted to be right-handed like his friends, so that last year he practiced switching off. I don’t think he managed the trick though. He never could get his shoes tied right.” Jim almost smiled, and caught himself in horror.

She didn’t say anything at first, and once again he felt like a fool with these people. He wanted to talk about his son, at least about some of the small things that maybe wouldn’t cut too close to the nerve (although it wasn’t always easy predicting what those things were going to be), and after Alicia ran away there’d been no one left to say those things to. But these people were the consummate professionals. They said as little as possible, and he always said

too much.

“I am not detecting as much strength on his right side,” she said. As if to confirm the statement, she rotated the flat of the bar over Mark’s nose, paused, then carried the edge up and down above his right cheek. Her hand was long and slender, slightly cupping the bar as she gripped it. A perfect finger glided slowly up and down the upper edge as if to guide and encourage. There was a subtle tightening of the skin covering Mark’s cheek, and a slight nervous pulse in the eyelid, but no other signs of life.

Jim felt his own face tighten. “He’s brain dead,” he made himself say, and could feel the skin around his eyes loosening. “I don’t know why you people keep doing this.”

She held the bar steady above Mark’s mouth, and looked up. “That is a rather old fashioned term, Mr. Melville. In this era it means almost nothing. We know little. In some ways far less than before. Certainly far less than we thought.”

Her eyes were slightly oblong, with no corners. They were able to stare, to hold with a look, better than any other eyes he’d ever seen. “You’re one of them,” he said simply. It amazed him that he hadn’t noticed before. She stared at him, unblinking, because she had no lids. The slightly bluish fluid that periodically glistened over her eyes made her look as if she had been crying, but Jim didn’t know for sure if the aliens ever cried or not. He wondered what it must be like, not being able to cry, no matter what happened to you. Then with a jolt, he knew. Because he’d always known.

Her unblinking stare was beginning to unnerve him, her eyes shining with the blue tears she would not release. He’d heard that the thick fluid also protected their eyes from the pollution in Earth’s atmosphere. “That is true,” she said. “If that disturbs you perhaps I can find someone else to continue your son’s treatment.”

“No, no, of course not. Your people brought us the treatments, so who better? I was just … startled. I never met an alien close up before … that’s all.”

She executed a barely detectable nod, as if in assent, or acknowledgement that she saw through his small awkwardness. Her eyes appeared to widen even further, as if reception were opening up. Like a flower. Her eyes took him in and made a reading. It was frightening.

For a moment he wondered what happened when an alien died, and there were no lids to close. Would the eyes change colour? Harden? What happened when the fluid supply stopped? He imagined alien blue eyes hardening to stone, a permanent stare into the secrets of the universe. His morbid speculations embarrassed him.

She turned and guided the bar down Mark’s legs. There was no movement at all.

“When do you decide a person’s dead?” he asked her.

“I do not decide. A committee decides. Sometimes they ask my opinion.”

“And your opinion here? Is Mark dead or isn’t he?” He wanted to rip the bar out of her calm, controlled, perfect hands. He wanted to stare into those perfect eyes, far bluer than any human’s eyes, bluer than any eyes had a right to be, until she had to turn away.

Her eyes seemed to grow larger. The movement of the fluid seemed more pronounced. He imagined ocean waves in the whites of her eyes. “You must miss your son very much,” she said.

Mark’s flesh appeared to breed shadows: vague, embryonic shadows just beginning to push their way out through the inner layers of skin. Each day there were more.

That night Jim dreamed he was kissed by a beautiful stranger.

*

He often thought of the last time he had kissed anyone. He and Alicia had spent eight hours at Mark’s bedside that day, during which time they feigned hope and optimism. There hadn’t been that much holding them together in the first place. Whatever they had originally felt they’d had in common had proved to be short term. Now Jim had a problem understanding how any two people could have anything in common.

There had been Mark. And there had been the sex.

“You don’t have to go back tomorrow,” he’d told her. “I’ll go. I’ll take care of it.” Little did he know. She lay on her stomach with all her clothes on. He’d started rubbing her shoulders.

“That feels good,” she’d said, but not as if she meant it.

He leaned over and kissed her on the back of the neck. He moved his lips slowly up to the back of her left ear. “I’m so sorry,” he whispered.

He could feel her tense beneath him. “Why are you sorry? You didn’t do anything wrong. Do you think I did anything wrong?”

“No, of course not.” He stopped and laid his cheek against her back. He could hear a roughness in her lungs. He could see Mark’s face darkening, Alicia frantically trying to pull the small plastic piece out of his throat, Mark’s eyelids dropping shut, showing the blue white crescents. They’d always been good parents, everyone said they were good parents. But Jim couldn’t fit that picture of Mark into any possible meaning of ‘good parents.’ “I’m just so sorry it happened. That’s all.” He felt his voice growing tight with an anger he’d never quite understood.

“Of course.” He could hear the same kind of aimless anger in her own voice. “Of course, we’re all sorry it happened. Being sorry doesn’t help. I just want him back.”

I want him back, too, he thought, but for some reason could not say that to her. “We don’t know that he’s …”

“He is. I would know.”

“But if he’s not, if he’s just out of it somewhere. We have to be here when he gets back.”

Alicia turned her face into the bed. Jim rubbed her neck, her shoulders. He opened his hands and ran them up and down her back and thighs, testing her strength, looking for any response. He made his hands receptive: for warmth, for life. He searched for the secret flesh where hope might be hidden.

He slipped his hand into the loose neck of her blouse, slid it over to cup her shoulder. He moved his hand in circles there, feeling where bone and ligaments joined together. He let his fingers glide to the other side of the shoulder joint, then pulled until Alicia was lying on her side.

Jim rolled over in front of her and tried to look into her eyes. She kept them closed, but relaxed as if she were asleep, showing those pale and hard to interpret crescents along the bottom edge. Her breathing was strained and shallow, as if she were forcing herself to sleep. Her mouth slackened like a child in sweet, never ending sleep.

The top button of her blouse had come undone. He rested two fingers there, spread them, moved them down to the next button, touched the hard plastic lightly with the tips of those fingers, as if it might cut or burn, as if his fingertips contained raw, expo

sed nerve endings. He slipped the button loose, and then the next, and the next.

Alicia’s arms rose up around him, as if she were floating away in her dreams. Her breasts floated out of her blouse. He whispered nonsense, and cloth evaporated into their breath. He closed his eyes and tried to dream his way into the places where she had hidden herself. His mouth and hands found folds and rises, hollows, dry and wet places. He probed with fingers and tongue for the secret place that would fill him, for the one flesh that would last, for the one depth or contour of the body that would not be a gravestone. And, once again, he could not find it. He could not be satisfied. He had never been able to be satisfied.

He allowed his lips to slip over her flesh, tasting her. He discovered spider patterns of broken blood vessels and could smell the coppery blood just beneath the top layer of skin. In the pewter moonlight, her body grew shadows.

“It’s not enough to be hungry,” she whispered in her dreams.

A few hours before dawn he awakened for a few minutes. He sat up in bed as if he had heard something, as if his body had said things to him in his sleep. He stared down at her sleeping form: moonlight had turned her face blue and silver, breathless. Her skin seemed to be slowly turning transparent, as if a memory. Where is she? He leaned over and kissed her as if he were kissing a beautiful stranger.

The next morning he was not surprised to find Alicia gone.

*

“It is like … mining,” the stimtech said. “Your people’s term, I believe. Sometimes you discover something.”

The stimtech moved the rod a little more quickly, as if carving the dead air over Mark’s body. Jim wondered, crazily, if maybe the dreams stayed close to you when you died, invisible yet fast to the body like a sack you cannot escape. He imagined some anonymous gland or duct in the body storing the immortal dreams.

She raised and lowered the bar, working it down the length of Mark’s body. Jim thought of divining rods, well diggers, séances.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

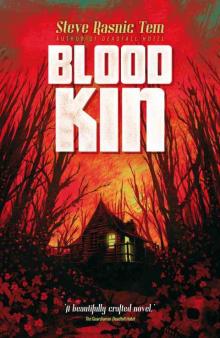

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin