- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

The Man on the Ceiling Page 15

The Man on the Ceiling Read online

Page 15

She doesn’t say, though someday she will: It was my introduction to the calm that can come from letting yourself float in the fundamentally unknowable without having to create sense and dimensions for it. She doesn’t say: I’ve had to learn that over and over again, I’m learning it again right now, but not quite from scratch.

She does say, “That book made me want to be a writer.”

Then, thinking of the little books the two of them have written and illustrated together since well before Christiana could read or write, Melanie suggests, “Would you like to write a book about it?” Long pause.

Then Christiana lifts her round wet face and regards her grandmother with a rare directness that casts the moment in amber. “Not now, Grandma. Maybe later.” Nodding, Melanie vows to hold her to it.

After dinner, after Christiana has again tried and not been able to stay the night, after Melanie has taken her home and they have watched the news together and she has gone to bed, commenting again on how you’d never know planes had fallen out of the sky just yesterday afternoon, Steve can’t sleep. Disaster is imminent, and it doesn’t help to assure himself that, if you look at it that way, disaster is always imminent, as is joy. He can’t stand it. He puts on his cap, gets the car keys, lets himself out of the house and into the garage, and goes for a drive. He doesn’t get anywhere. He gets lost for a while. When he rediscovers his own house in his own neighborhood, his own wife asleep inside not even aware that he’s been gone, he slinks back inside and climbs the stairs to sit in the attic in the comfortable chair, shaking. No danger made itself known to him tonight, which intensifies his fear. The man on the ceiling is out there, on the ceiling of the world, masquerading as a star or a flock of night birds or the wingtip lights of a doomed plane, just waiting for the right moment to squash himself against Steve’s windshield and make him drive off the road or into oncoming traffic, into the path of cars carrying everyone he’s ever loved.

Chapter 9

Asymptote

Moments cast in amber. Invisible rooms. Reality puddling. Breakthroughs from and into the divine. I hasten to protest: Steve and I don’t always live like that! Not everything is fraught with Meaning. Like everybody else, we bumble through most of our daily lives attending to basic maintenance: doing laundry, going to the dentist, stocking up for whatever disaster might come, getting a haircut, walking the dogs, earning a living.

But even in the daily doing of what must be done, transcendence finds a way to creep in.

I’m a social worker for an adoption agency. Mostly I work with families adopting older kids who, because of abuse and neglect, have been taken away from their biological parents and need new ones. The job suits me, combining as it does a host of mundane details in service of a risky and world-changing endeavor. On my monthly required visit to an adoptive family, I sat at their dining room table and chatted with these extraordinary parents about healing. Their little boys, still toddlers, had increasingly been showing us that already they were on far more intimate terms with the man on the ceiling than any of us, in our naiveté, would have thought possible. My job is to be of help; I wasn’t sure how much help I was being. The boys played under our feet.

Then the father said gently to me, “Well, you know, it’s an asymptote.”

“A what?”

He spelled it for me. “It’s a mathematical term.” He drew it for me on the back of one of the kids’ drawings, a line on a graph coming closer and closer to the vertical axis and never quite reaching it.

“I probably learned that in geometry class, right?” But it seemed an utterly new term. My senses were hyper-alert. My skin was tingling. I knew this was one of those moments. The younger boy ran his Matchbox car across my shoe and giggled.

The father tapped his pencil on the paper. I noted that he had used a pencil, with a full eraser.

“We can get closer and closer to helping them heal,” he said, indicating the line that curved up and to the right. “And we’ve already come a long way from where we started,” bouncing the tip of his pencil in the lower left quadrant where the curving line started. “But it’s by nature an asymptote. We’ll never get all the way there.” He tapped the hypothetical point at which the line would cross the vertical axis.

The older boy said my name in his endearing way and offered me a plastic candy bar to pretend to eat. I did. He watched me closely to be sure I did it right. Trying my best, I said to his father, “Is that enough for you? Coming closer and closer? Because for some adoptive parents of traumatized children, it isn’t, and once they realize they’ll never get there, they give up.”

The question seemed to surprise him. “Oh,” he said, with what I took to be weariness and joy and great love in his voice, though I could have been wrong, since that’s a lot to read into two words, “Sure.”

I have his drawing on my wall, like the Little Prince’s drawing of a sheep. Learning about asymptotes has changed my life.

But then, everything changes your life. Everything gets you closer and closer.

Our oldest son is in and out of our lives.

That’s not precisely accurate. He’s never fully out of our lives; he’s our son. He’s never fully in our lives, either; even on those very early mornings not so long ago when he and I sat together in the kitchen drinking coffee and talking about being a parent, being a child, being a sibling, being a life partner—talking, that is, about love, and how hard it is, and how necessary—even then, I never knew if we were really in touch.

By choice and by circumstance, the worlds Chris and I inhabit have only a few points of intersection. That there aren’t more of them, and that they are so unreliable, is tragic. That there are any at all is a miracle. It’s how you frame it at any given moment. It’s a matter of which is foreground and which is background.

We first met our son on a winter day I remember as chilly, gray, windswept, at the farm where he and five or six other foster boys lived. He was ten. We had been married two months. None of us had any idea what we were doing. Not that, on those rare occasions when we are aware of being on the brink of a life-changing adventure, we ever know what we’re doing; when it comes right down to it, every step every one of us takes is stepping out into the void.

Chris had been told who we were and what our intentions were toward him. He’d been waiting. On those long, straight, open high-plains roads. Our approach must have been visible for miles. The foster mother had managed to corral him into the house, but when he saw or heard us pull into the gravel driveway he hustled out the back door. We realized later that he must have seen us well before we saw him; at the time, we didn’t feel his eyes on us.

He wouldn’t come in. We sat in the living room of the farmhouse making small talk with the foster mother and the social worker, and every once in a while one of them would say, indicating the gray open space framed by windows on either end of the room, “There he is. There he goes again.” We began to understand that our son was circling.

The foster mother was losing patience. A large, gray-haired woman without much noticeable warmth, she stomped in front of us to open the door and yell, “Chris! Get in here! You hear me? Get in here right now!” There was no response from our son; he certainly didn’t obey her command. Scowling, the foster mother grumbled as she returned to her seat on the green couch that he never did as he was told. This would turn out to be a major understatement.

The social worker went outside. He was gone a while, and the foster mother excused but didn’t explain herself and left the room, so Steve and I sat alone together in this stranger’s house on the brink of becoming parents, waiting for our son to come to us. When the social worker returned he was flushed and breathless from the cold and the chase, and shaking his head in a sort of exhausted admiration for the defensive skill of this wounded, eager, cynical little boy.

The social worker—a bluff, stocky, blond man dispassionately accomplished at this work he’d been doing for many years—reported he’d used up his entir

e bag of tricks: light reassurance (“They won’t bite you,” a patently untrustworthy promise to a child who’d been bitten so many times in so many ways), grief work (“You’re not going to live with your birth mom anymore. I know that’s hard to hear. But you have to let her go”—advice nonsensical to Chris then and now), paradoxical intention (“You know what, Chris? You’re not allowed to come inside. I don’t want you to meet these people”—a game at which he’d more than met his match with this one).

Chris, the social worker told us, was running, strolling, kicking stones, climbing fences, chasing cats, following groundhog trails—doing all manner of things at the same time, but, under it all, circling. Getting closer, so that we’d see his pudgy form and sleek black hair and round face looking in the windows at us or pointedly not looking in. Swinging out as far as he could within the big fenced yard, maybe even going outside the fence at times although that wasn’t allowed. Approaching us, but never quite getting there. Taking himself far away from us, but never quite all the way.

I don’t remember how this standoff was resolved—the first of many; we’re in one now.

I’d like to report that Steve or I went outside and sat quietly somewhere on the unsheltered prairie until he could bring himself to come close. That’s what we should have done. But we didn’t know to do that. I’d like to tell you his need to attach won out over his need not to, finally and forever letting our son break free of the elastic line that had kept him spinning just out of reach, but that isn’t what happened. I don’t know what happened. I can’t bring back to mind how we went from that point to the next and to this point where we are now.

Chris is well past thirty now, and still circling. So am I. I think we come very close to each other every once in a while, although I could be wrong. Then, I think, he shoots wildly out to the very farthest rim of the orbit. Either place is dangerous for all of us. Either place is, among many other things, love.

The Yellow Cat

Something Gabriella had noticed about cats was how they stared. They’d be sitting there all relaxed on the windowsill in the sun or on top of the laundry basket full of towels just out of the dryer or on her bed, and all of a sudden they’d be staring at something people couldn’t see. You could tell by their eyes, or even if their back was to you and you didn’t see their eyes.

She tried to stare like that. She tried to get really quiet and make her eyes go glassy and breathe in kind of a rhythm. But she never saw anything but what she always saw. Maybe that was because she was a person and not a cat. But maybe she could learn.

She liked thinking that people didn’t see everything. She liked thinking that different people saw different stuff. Like Grandpa. He stared, too, and she thought he saw and heard and maybe smelled weird stuff. She liked that. It also gave her the creeps.

Gabriella’s cat Cinnabar stared. Cinnabar was the name for some Chinese stone that was kind of a gold-red color, like her. She was an old cat, almost thirteen. Gabriella was thirteen, too, but it didn’t mean the same thing in cat years. Cinnabar still played with yarn once in a while and she still rolled in the weeds and got her fur all clumpy and then wouldn’t let you cut out the mats. Her favorite things were sleeping on Gabriella’s head, eating tuna fish, and staring.

In Gabriella’s opinion, “Cinnabar” was a weird name for a cat, but she didn’t have anything to say about it because she wasn’t even born yet when Cinnabar was born. That was a weird thing to think about. Where was she when Cinnabar was born? Where was Cinnabar before Cinnabar was born? Just lately she’d started to think about stuff like where did you come from and where did you go when you died? Mom said we’ll never know, which made Gabriella mad. Not knowing stuff was dangerous.

Gabriella’s grandpa never used to like cats.

Ever since he and Grandma came to live with Gabriella and her parents, he complained about Cinnabar’s long yellow fur all over the place and how she clawed the furniture, and he’d say mean things like, “Cats don’t care about anything but themselves,” and “Cats are sneaky. You can’t trust ‘em as far as you can throw ‘em.” Gabriella used to be afraid he was going to throw Cinnabar or something, but as far as she knew he never did. He better not have.

She wasn’t their real granddaughter. She was Dad and Mom’s real daughter, because real wasn’t about whether you were adopted or not. It was about something else, something about imagination. She didn’t exactly understand it and she didn’t want to think about it enough to figure it out.

She thought about it a lot anyway, in the back of her mind, kind of like the watercolor washes they had to do in art class, where you covered the whole paper with some pastel color and then painted stuff on top of it. What was real? What made Mom her real mom and Dad her real dad and herself their real daughter, when she wasn’t born to them and most people, like most of her friends, thought that made it not real?

It had something to do with if you could imagine it. Mom and Dad could imagine it. She could imagine it, too. Grandpa and Grandma couldn’t, or didn’t want to. It was like their imagination muscle wasn’t strong enough, or they were afraid for some reason. In a way, Gabriella understood that. Imagining yourself real was scary.

They were nice to her, usually, the way you’d be nice to somebody else’s kid. It was like her being their granddaughter was this idea in this other world they couldn’t quite get to, and so she couldn’t quite get to it, either. Almost, but not quite. Closer and closer, but never all the way.

The ancient Egyptians thought cats could guide you through the underworld. That’s why the Pharaohs buried cats with them in the pyramids, because they thought they’d need them in the underworld, which is where they thought you went when you died. Grandpa had told her that one time when she was little, and it had scared her, and she kept thinking about it, and finally she’d decided not to believe it. He didn’t remember saying it, but she couldn’t forget it. Now it was in her history book, too, and there was a big test on Monday, and she really couldn’t stop thinking about it.

So she was sort of worried that it was the underworld Grandpa had one foot in and he’d try to take Cinnabar with him. She was worried that he’d go away and Cinnabar would go away and she’d never know what this underworld place was. She was even more worried that they’d try to take her with them, and that she would want to go.

Now she didn’t think Grandpa even knew what a cat was. He was really old, and he had some kind of brain disease. He hummed more than he talked, not any actual song but just this noise like somebody twanging a rubber band. Most of the time he didn’t know anybody, even Mom and she was his real daughter. That made Mom feel bad. Grandma was mad all the time. Mom said that was because she was scared, and besides, his humming drove her crazy. It was the first time Gabriella had thought about how being scared could make you mad.

Sometimes Gabriella wondered if Grandpa even knew who he was. Not just if he knew his own name, but if he knew who he was.

Sometimes Grandpa would get upset and he’d yell or make this kind of groan. Sometimes he looked all relaxed and peaceful. Gabriella would sit with him and hold his hand, or not touch him but just sit there and stare at him, and try to imagine what he was seeing.

It would be cool if she could see things like Cinnabar did or like Grandpa did or like anybody but a thirteen-year-old girl named Gabriella did. It would be scary, but it would be very cool.

Once in a while he talked to her. She didn’t think he knew he was talking to her, exactly, but he said stuff that was weird and neat and creepy and nice. He said, “I love you” a lot, and he never used to. Mom told her he hardly ever said he loved her, either, even when she was little, which was really sad and made Mom’s eyes fill with tears and made Gabriella wonder if maybe Mom wasn’t his real daughter after all. She said she didn’t think he knew how. Now he did.

One time he told Gabriella, “I’ve got a foot in the other world already.” He didn’t explain what that other world was, but she sort of understood, a

nd so she thought maybe it was that other world that he stared at.

One time he told her, or she just happened to be in earshot when he said, “There’s a car waiting in the woods for me.” She wanted to go there with him. She didn’t ever want to go there. What she wanted was to know what it was like without ever quite having to go there herself.

Cinnabar sat on Grandpa’s lap a lot. He petted her. Gabriella wasn’t sure either one of them really knew the other one was there. Or maybe they both knew they were both there but it didn’t matter who either one of them was. Whatever. She could get really confused thinking about that, and sometimes she couldn’t stand to be around them because they made her feel too weird and left out.

But then she’d just sit in the same room with them, when Cinnabar was purring and Grandpa was humming and they were both staring. She’d quit trying to figure things out. She’d just sit there. Then sometimes she’d feel peaceful and excited at the same time, and sometimes she’d know the world was about to end.

Mom worried, but she worried about the wrong stuff. Parents did that a lot. “Gabriella.” she’d say, “I’m sorry. I know it’s hard having Grandpa and Grandma living with us.”

It wasn’t hard. It was weird, kind of, but it wasn’t hard. Not any harder and not any weirder than having Cinnabar live with them, and she had been there longer than Gabriella had, so actually you’d have to say Gabriella was living with Cinnabar instead of the other way around and maybe that was weird and hard for Cinnabar.

Today was Saturday. It had snowed in the night and it was still snowing in the morning. When Gabriella got up, Cinnabar was on the windowsill of the bay window in the dining room, all straight and tall like those cats carved out of smooth wood, with just the tip of her tail twitching. Her feet made sort of a point and her shoulders were hunched up, so she was sort of shaped like a heart. Mom and Dad had a picture Gabriella had made when she was a little kid of a cat shaped like a heart and with feathers on its feet. It was dumb. She wished they wouldn’t keep stuff like that, like it was important or something. She wished she’d just kept the heart-shaped cat with feathers a secret. Too late now. Whatever.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

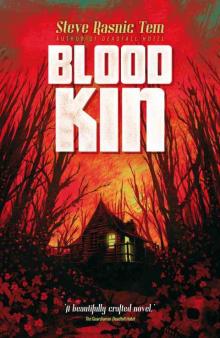

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin