- Home

- Steve Rasnic Tem

The Man on the Ceiling Page 16

The Man on the Ceiling Read online

Page 16

Cinnabar was probably watching the snow. Or maybe there was a bird or a squirrel in the vine. Sometimes in the spring the birds and squirrels would get surprised by a snowstorm and they’d get in between the vine and the window to keep warm, and you could see them right up close, like they didn’t know you were there, or they knew you couldn’t catch them through the glass, or they didn’t know what you were. Gabriella wondered if there was a window she didn’t know about and somebody or something was on the other side of it watching her, and if they could get to her they’d hurt her or they’d keep her safe, but they couldn’t quite get to her.

“Gabby, go call Grandma and Grandpa for lunch,” Mom said.

She was watching this funny movie, and she was all wrapped up in the blanket Grandma had made a long time ago out of these bright little squares called Granny squares, and she didn’t want to get up. So she didn’t.

“Gabriella.”

“Okay.” But she could wait. Mom wasn’t yelling yet.

“Gabriella!”

“Okay! Whatever!” It wasn’t fair. Why couldn’t Mom go get Grandma and Grandpa herself? They were her parents. Gabriella got up, kept the afghan around her shoulders, stood in the doorway for a few more minutes to watch while the guy in the movie got a bucket of water dumped on his head, and then she went. She wasn’t happy about it, but she went.

Cinnabar was still sitting on the windowsill, in the same spot, at the same angle. The tip of her tail was still twitching, exactly the same length of it, exactly the same distance back and forth, exactly the same speed. When Gabriella passed by her on the way to the back of the house where Dad had turned a couple of rooms into a little apartment for Grandma and Grandpa, she stood on tiptoe and looked down over Cinnabar’s head.

Big surprise: she was staring. Her eyes were the same color as her fur and right now they were huge, and her ears pointed straight up. When Gabriella moved back and forth, the cat’s eyes didn’t follow her.

She’d never seen Cinnabar stare up before. All the way to Grandpa and Grandma’s, she wondered what was up there, and she wanted to see it, and she didn’t want to.

Grandma said, “I can’t go to lunch. He’s having a bad day.” She kind of smiled and winked, like the two of them had a secret together and Grandpa was left out of it.

“What’s wrong?” This room that used to be the guest room and was now their living room, but Grandpa wasn’t sitting in his favorite chair. Lately he hadn’t always wanted to sit here, and Grandma and Mom were worried he’d get lost. Maybe he’d go to that other world. Maybe Gabriella could go with him. Just for a visit.

Grandma started to say, “He doesn’t—” and then you could tell she decided Gabriella was just a kid. This time her smile was totally fake. “He’s just a little confused, Gabby. You better go get your mother.”

Gabriella got stubborn when adults thought they had secrets from her and she knew perfectly well what the secrets were. Maybe it was mean, but she asked, “What’s the matter, doesn’t he know you today, Grandma?” Usually she wouldn’t ask something right out like that.

Grandma got tears in her eyes, and Gabriella felt terrible. For some reason, it had never occurred to her that somebody as old as Grandma would cry. That was one reason she didn’t ask stuff right out: she was always afraid something important hadn’t occurred to her.

Grandma sighed and went over to the stove to stir something in a pot. Gabriella smelled chicken noodle soup. Homemade. Campbell’s was better. “Go get your mother. Please.”

“You go. I’ll stay with him.” Why was she saying that? She didn’t want to stay with him.

“You can’t handle him. What would you do if he walked out of the house?”

Gabriella shrugged and made her voice sound like this was a dumb question, which it wasn’t. “Whatever. Walk with him.” It was the only thing she could come up with. She didn’t know if it was right or not.

“He won’t talk, you know. He just hums.”

“I could hum with him.”

Grandma glared at her, and Gabriella thought she ought to say that wasn’t supposed to be a smart remark.

“What would you do if he called you by some other name? Say, Melanie?” Melanie was Mom’s name.

“I wouldn’t care.” She would care. She was making this up.

Grandma sighed again. Finally she turned off the burner and put the lid back on the pot and said, “He’s in bed. He won’t get up. Maybe it would be okay for a few minutes. You can have some soup.”

She was proud that Grandma would trust her. All of a sudden she was also scared to death. She actually didn’t have a clue what she’d do if he started acting really really weird. She was going to do this wrong, whatever it was. She was always doing things wrong. She could think of a million ways she could mess this up.

For just a minute, she thought she might just not do anything. Stay here in the kitchen that used to be the family room and not eat any homemade chicken noodle soup and not take any to Grandpa, either. Grandma didn’t tell her to give him soup.

Or leave Grandpa alone and go hide in her room and say she thought Grandma was coming right back. Or run away.

Finally what she did was ladle some soup into two bowls, put spoons in them, and carry them into the other room, which used to be Mom’s office and now was Grandma and Grandpa’s bedroom. Cinnabar led the way, her tail up straight. Well, she didn’t exactly lead, because you could tell she couldn’t care less if Gabriella followed her or not. It was more like she showed the way. Guided. Gabriella hadn’t noticed her come in, but she was glad for her company. If you could call it company. Maybe Cinnabar could show her what to do. Somebody better show her what to do.

Grandpa was propped up against a reading pillow. He was humming, and his one finger on top of the blue blanket was twitching like Cinnabar’s tail. He didn’t have his false teeth in so his mouth was all pushed in and disgusting, and he was staring up at the ceiling. Gabriella looked up there, too, but she didn’t expect to see anything and she didn’t.

“Grandpa.” Her voice was a lot louder than she’d thought it was going to be, so she got embarrassed. “It’s me, Gabby. Are you hungry? Grandma made us some chicken noodle soup.”

He didn’t pay any attention. Cinnabar jumped up on the bed and settled herself in front of him, where his lap would be if he had a lap, but his legs were too skinny and crooked to call it a lap anymore. She turned around with her back to him and sat up tall like a carved cat and the tip of her tail started twitching again.

“Okay, whatever.” Gabriella gave up on the soup. Maybe Grandma would be mad, but Grandpa wasn’t interested and she wasn’t, either. She put the bowls on the dresser and then just stood there, trying to figure out what she was supposed to do.

If you didn’t do what people wanted you to do, you got hurt. Even if you did, you got hurt. And they didn’t tell you what they wanted you to do, or they changed their minds, or they tried to trick you. Grandpa wasn’t telling. Cinnabar wasn’t telling. Gabriella didn’t know what to do. She was going to get hurt.

She took a couple of shaky steps toward the bed.

Now she was looking down on them. Grandpa had been bald all her life. In fact, Mom had pictures of him when he was about twenty-five, and he was bald then. Right now the top of his bald head was shiny, and there were spots on it. The top of Cinnabar’s head was furry, and a weed was stuck behind her ear, but Gabriella knew better than to try to get it out because Cinnabar would scratch.

She put her hand on the top of her own head. Her hair was all flat. She was sick of messing with it. She just wasn’t good with hair.

Both of their eyes were turned upward. All four of their eyes, Cinnabar’s golden and Grandpa’s brown and just as glassy as the cat’s. They were staring at something but definitely not at Gabriella.

Out loud she said, “Let me see.” Just saying it out loud was scary. She didn’t like calling attention to herself. Nobody answered. Nobody was ever going to answer. Mom a

nd Dad promised they’d answer her, promised they’d be with her and go ahead of her and show her the way, but they weren’t here right now, were they?

Then Cinnabar said—her name. It wasn’t “Gabriella,” but it was her name.

Grandpa said, “Come on. You can come with me. I’ll show you.” Or something like that. He got up. He almost fell, and Gabriella reached out and took his hand. She had to go with him or he’d fall or he’d get lost.

The three of them were moving. It wasn’t walking or running or swimming or flying or any other word Gabriella could think of for ways you could move, but it was moving. Cinnabar went first, her tail straight up. She wasn’t looking back, but Gabriella could tell they were supposed to follow her.

If she followed Cinnabar and Grandpa and went wherever it was they were going, she would get in trouble. If she didn’t follow them, she would get in trouble. When Gabriella really thought about it, she knew she didn’t get in trouble with Mom and Dad a lot, and she knew they wouldn’t hurt her or leave her or quit loving her, no matter what she did, but down deeper she always knew it would happen, it would happen, down deep she was just a tiny baby and the big people who were supposed to take care of her got mad because she did something wrong, she was just a tiny baby and she did something wrong, and they grabbed her and yelled at her and then she was flying through the air and then her head hit the wall and broke. Her head broke. She did something wrong and she got in trouble and they broke her head.

She held onto Grandpa’s hand. He didn’t hold her hand back, but he didn’t pull his hand away, either. She had to go with him or he’d get lost or she’d get lost.

They weren’t going up or down, exactly, but more like out or maybe in, which somehow would feel the same. Or maybe the world, whatever world this was, was moving around them and they were standing still. When she tried to think about it that way she got kind of dizzy, like when she tried to think about the earth turning in space or the sun staying still and the earth rolling around it. The sun didn’t actually rise or set, so why did people say “sunrise” and “sunset”? It was a trick.

Apparently they were outside now. She didn’t recognize any of it, but Grandpa and Cinnabar seemed to. There were things like clouds that weren’t clouds. There were things like angels and ghosts. There was something on the ceiling or the sky—except that it wasn’t a ceiling or a sky—that kind of made her think of a huge spider, and she didn’t like spiders, but it also made her think of a man, the shadow of a man, a paper-doll man come to hurt her and to guide her and to tell her secrets all at the same time, and to steal her away.

Cinnabar had feathers on her feet, and then she didn’t. Grandpa was holding something out in front of her that Gabriella knew was a dragon’s wing without the dragon. What would Grandpa do with a dragon’s wing? What would she do if he gave it to her? Go look for the dragon?

What was a dragon anyway? Dragons didn’t really exist, but she thought she knew what they were. She wouldn’t say that to anybody but Cinnabar and Grandpa, and she wouldn’t actually say it to them, but she knew what a dragon was. She’d met dragons before. She’d lived with a couple. She’d been born to them. Did that make her a dragon, too? What would it mean to be a dragon? Or a dragon’s wing? If she kept thinking like that she was going to get lost.

So they walked—or swam or flew or rolled like the earth or slithered or whatever it was they were doing—for a long time. Or a millisecond. Or else it didn’t have anything to do with time at all. Whatever.

They came to a big hump, or the hump pushed up in front of them. It reminded Gabriella of the snake-that-swallowed-an-elephant in The Little Prince. Maybe it was just a pile of leaves and branches, but she had the impression there was something hard inside like the armatures they used in art class when they were doing clay.

Grandpa hummed, “There it is. Waiting for me.” Cinnabar must have buried herself in the hump of leaves. The leaves were almost the same color as she was, only duller, and they wriggled and poked up and jumped because the cat was moving around under there. Maybe it was the cat. Gabriella guessed it could be something else. She didn’t know what.

Grandpa fell. Gabriella yelled, “Grandpa!” and grabbed his arm and tried to get him up. His arm was like a really thin branch and she thought maybe it would break and she’d be standing there holding half his arm like a broom. That would be embarrassing.

He jerked his arm away from her. He was a lot stronger than she’d thought. He fell again, but this time she realized that he didn’t fall, he dived. Was that her fault because she didn’t hold onto him? How could she hold onto him? And, anyway, he didn’t want her to. No matter what she did, she was going to get in trouble.

When he threw himself onto the mound, he thumped, so it must be hard underneath just like she’d thought. She was sort of proud of herself that she’d known that. He was clawing with his hands to clear away the leaves and branches. Where was Cinnabar?

It was a car. There was the top of it, shiny and reddish-purple. There was a window, but you couldn’t see inside. There was a door. Grandpa was working to get it open. She didn’t know if she was supposed to help him or not. An old-fashioned car, funky, all rounded like a Beetle but squarer.

Grandpa got the door open. She didn’t think it should have been that easy, but he was inside the car now, and Cinnabar was curled up on the dashboard like one of those fuzzy toys you hang from the rearview mirror, only bigger. Gabriella’s eyes and nose itched from all the leaves, and her shoes were damp. How was she ever going to get Grandpa out of the car? She couldn’t leave him here while she went to get help, so it was up to her.

“Grandpa, come on, let’s go home.” She jumped when the horn honked long and loud. She didn’t like getting scared like that, and now she was mad. “Stop it!” she yelled, and the horn honked again. Fine, let him sit in there all he wanted, turning the steering wheel and stomping on the pedals and honking the horn. The car had been in the woods buried under leaves and dirt for a long time. It was amazing the horn worked. Obviously the engine wasn’t going to start. Obviously Grandpa wasn’t going to really drive, no matter what he thought because he was crazy and didn’t know what was real and what was made up. He wasn’t going anywhere.

The engine sputtered a few times and then started. The car moved, backed up. Big clouds of leaves and dust poofed, and she sneezed three times like she always sneezed. Grandpa was grinning at her through the cracks and bird doo-doo on the windshield. She’d never seen him grin like that before. Cinnabar was yellow like a fat pile of leaves on the dashboard. Grandpa honked the horn again and made that motion with his curled-up fingers that meant “come here.”

She couldn’t just let him drive off by himself. She couldn’t let him and Cinnabar leave her. “Wait!” She started running after the car, which was moving pretty fast now, backward and downhill. She chased it and chased it, and her chest hurt and she was dizzy and her legs hurt and she got close, touched the headlight once and burned her fingertips. Old-car exhaust made her cough and choke. She got close enough to see that Grandpa had his eyes closed and his head down and he wasn’t looking where he was going and he wasn’t looking at her anymore.

But Cinnabar was. Cinnabar was sitting on the hood of the car, outside now, tall and straight like an Egyptian guide cat, and her yellow eyes were staring right at Gabriella like lights. When Gabriella pushed herself forward and got a hand on the door handle, Cinnabar hissed and jumped onto her face—flew, really, except cats can’t fly.

Now Gabriella couldn’t see. Her nose and mouth were full of Cinnabar’s fur. All she could hear was hissing and purring, like Cinnabar was mad at her and loved her at the same time. She felt softness, and warmth, and Cinnabar’s weight—less than you’d think because most of her was fur—and then she felt, for the second time in their lives together, two sharp pokes, one on each side of her head, Cinnabar’s claws puncturing the skin at her temples.

“No,” the cat told her. “Stop.”

Gabriella burst into tears. Cinnabar pulled her claws out and dropped to the ground, landing on all four feet the way cats do. Gabriella touched her temples, afraid of what she’d find, but there wasn’t any blood and now there wasn’t any pain, just the memory of the cat’s sharp claws. Cinnabar was gone. The car was gone. Grandpa was gone. She was all alone. She’d come close to something, but couldn’t quite get there. She knew her way home.

Now Mom worries that being with Grandpa and Cinnabar when they both died will scar Gabriella for life. Parents worry about all the wrong things.

Something is about to happen. The organism reacts to danger it cannot possibly identify, only the sense of danger, only the certainty. It curls up. It puffs itself up. It does everything in its power to make itself either ferocious or beneath notice, impermeable or absorbent, battling to keep the danger out or to take it in. It insists that naming will make the danger real and therefore manageable; it ought to know better by now. It comes as close as it can to the danger without actually encountering it.

Maybe the date on the big kitchen calendar has sounded the alarm, not starred like birthdays and adoption days and wedding anniversaries, instead circled or underlined, as if it could ever be forgotten. But children far too young to grasp the concept of a calendar seem to feel it, too, this sense of impending doom which is not impending at all but has already come to pass. Maybe it’s the slant of light or the alteration of birdsong. But blind and deaf people feel it, too. Something, something dreadful, is about to happen, about to happen again.

Maybe it’s the quality of the air, this year soft and smooth and carrying a fragrance that has nothing to do with flowers. But some years it’s been wintry, and once or twice an early heat wave has implied that spring could be skipped altogether, and no matter what the weather, no matter how the air feels on its exposed surface, the organism knows that something, something is about to happen.

City Fishing

City Fishing The Man on the Ceiling

The Man on the Ceiling The Book of Days

The Book of Days Absent Company

Absent Company Deadfall Hotel

Deadfall Hotel Celestial Inventories

Celestial Inventories Ugly Behavior

Ugly Behavior Ubo

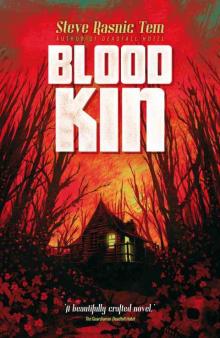

Ubo Blood Kin

Blood Kin